I recently made a sort of pilgrimage to the British Library to look at some of their illustrated editions of the books of Pierre Louys; a confession- I’ve written a lot about these but I’ve substantially relied on images found online- other than for the 1932 Collected Works published by the Pierre Louys Society of America. I wanted to experience some of these books in my hands because, as regular readers will know, I have put considerable stress on the significance of the bibiology of Louys- the astonishing number of illustrated editions of his works that people have felt it worthwhile producing. The experience of the book as a physical, tactile object can be every bit bit as valuable as reading the text, in addition to which I wanted to see the various colour plates as they had been designed to be seen- on the page and at the size that the artist had intended. This was the visit I looked at the very rare poem Maddalou as well.

I’ll start with the most outrageous- the 1933 edition of L’Histoire du Roi Gonzalve s et les douze princesses. It was tiny- just 10 by 7.5 cms; perhaps this was to enable something potentially illicit to be smuggled more easily; certainly, the book pretends to have been published in Madrid, which was probably intended to throw the authorities off the scent. This edition (which only totalled 205 copies) is illustrated with a dozen pen and ink drawings by Auguste Brouet. The unfinished story concerns King Gonzalve’s incest with his twelve daughters and Brouet faithfully reproduced these incidents in explicit detail. That said, the pictures were very small indeed, which must rather have detracted from their impact.

Next, a couple of real treasures. I looked first at the 1898 edition of Louys’ version of Leda, generally found now as part of the collection Crepuscule des nymphes (Twilight of the Nymphs in the 1926 Collected Works). As I’ve described before, this original version is illustrated with plates by Paul-Albert Laurens. It is a truly beautiful book, to hold and to look at. It’s printed on thick verge d’Arches paper and the illuminated initial letters and tailpiece illustrations are handpainted in watercolour. In places, I could see where the paint had strayed over the printed outlines and, in one case, over the frame of one of the decorative capital letters. Only 600 copies were printed, of which this was number 183- it was gorgeous, a little jewel.

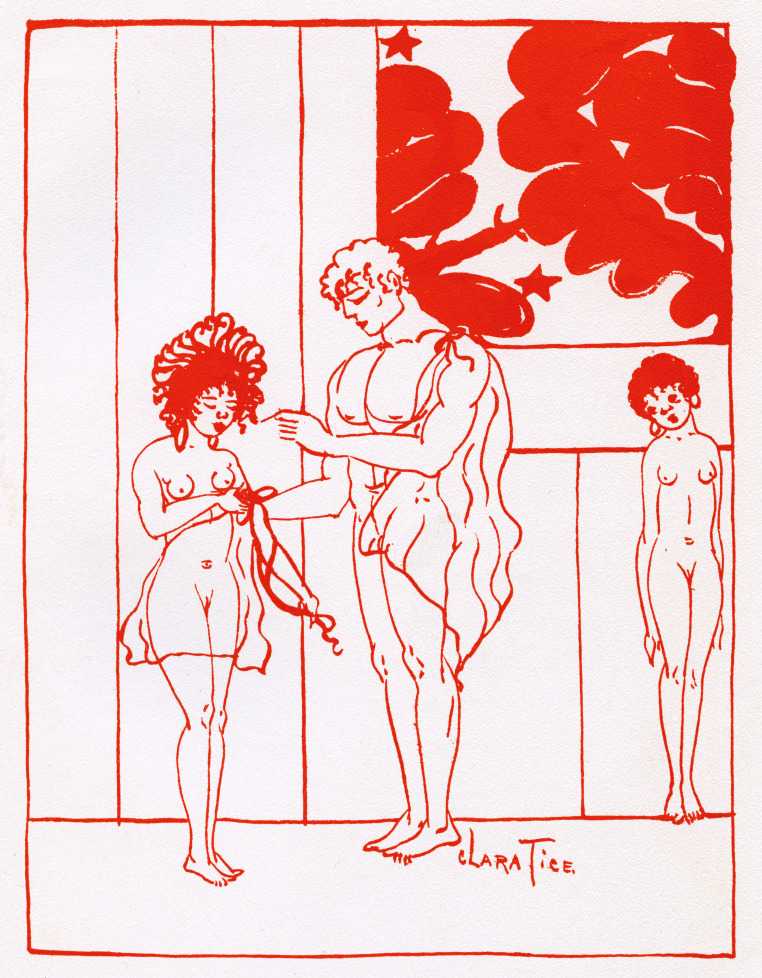

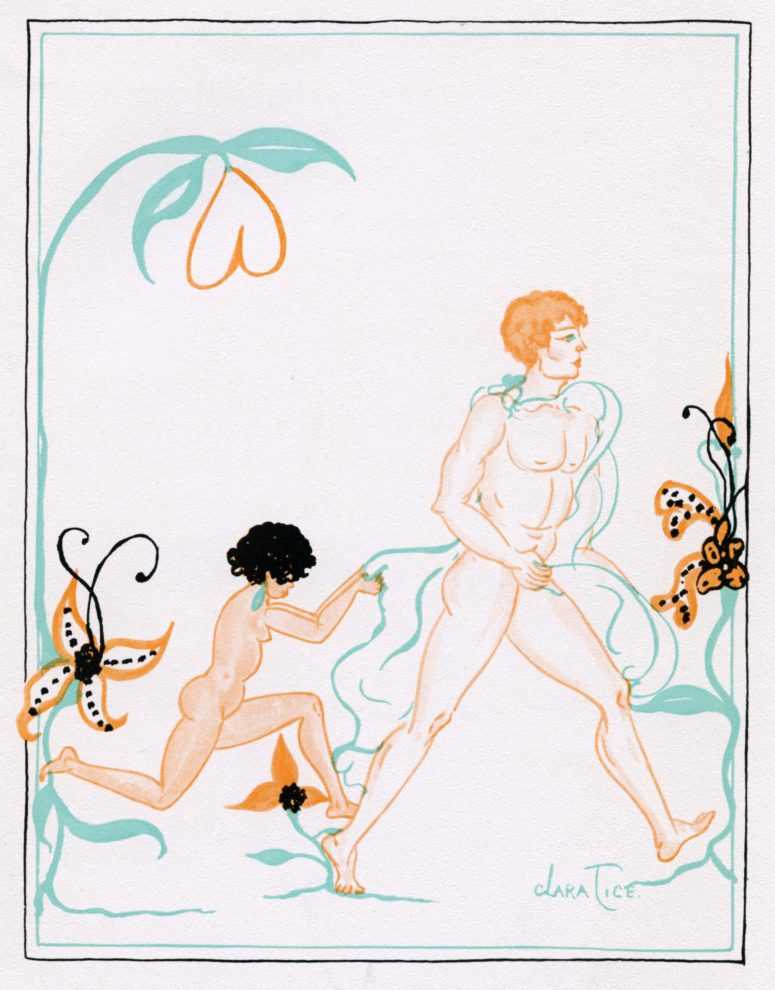

Nearly as lovely was the 1926 edition (for the Pierre Louys Society) of The Adventures of King Pausole, illustrated by Clara Tice. This was copy 586 of 990. The book itself, like my copy of the 1932 Collected Works, was decent but not top quality; the text was the same translation in each. The pages are moderately heavy paper, typical of middle of the range books of the time, but what lifts this edition is the plates- ten of them- by Tice. These are little jewels, printed in bright pinks and greens but, in some cases, with radiant backgrounds of silver or gold. The figures are, predominantly, Tice’s sweet female nudes; her drawing is dynamic and the designs are elegant. It was a joy to turn the pages. There’s a delightful humour in Tice’s work- from the odd phallic sceptre carried by the king to her young females, who always look slightly startled, their mouths in a cute moue.

Next I looked at the 1946 edition of Aphrodite, illustrated by Andre Collot and published by Henri Kaeser in Lausanne. The plates were printed on heavier paper than the text; a total of one thousand copies were printed and this seemed to be reflected in the fact that it felt less special and expensive than the books I’d already inspected. From 1930, I also inspected a copy of Douze douzains de dialogues illustrated by Collot. Although it lacked any bibliographical information from the publisher, the pages were thick, heavy paper, untrimmed (and unnumbered) and there were attractive floral pattern endpapers. The text was reproduced as if it was handwriting and the plates were minimalist pen and ink sketches, but it was notable how well the artist had captured the various facial expressions of the protagonists.

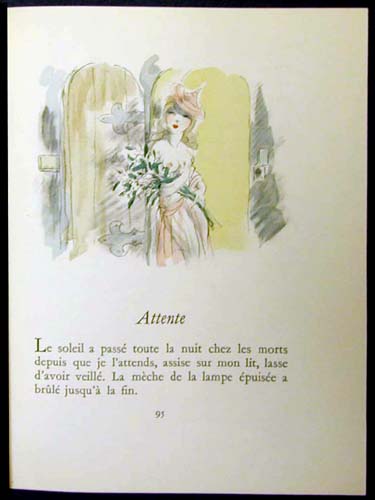

All the same, the next volume, Les Chansons de Bilitis, illustrated by Mariette Lydis in 1934, was number 1550 copies out of a total print-run of 5000- yet it felt more precious than the 1946 Aphrodite. Perhaps this was because it was printed on velin chiffon paper rather than plain old velin blanc– although the marbled endpapers may have helped? Maybe it was just because I esteem Ms Lydis more highly as an artist. She was generous- thirty four images, mainly included as tailpieces to the individual songs. In the copy I saw, these were printed just in black and white, but I have seen online coloured versions which have some differences in the drawing too. As ever with Mariette Lydis, these were delicate and tender evocations of female beauty and women in love.

Also illustrated by Lydis in the same Union Latine d’Editions series was a copy of Les Aventures du Roi Pausole. It was in the same format as Bilitis, with attractive marbled end papers and quality, heavier paper for the illustrations. There was a title page image of a young woman’s head, and eleven ‘tipped in’ plates on separate sheets bound into the text. These were in Lydis’ typical soft pencil drawing style; interestingly, one plate- showing Aline at theatre, catching sight of Mirabelle for the first time- was coloured; the only one on the book. As ever, Lydis produced beautifully modelled female nudes and delicate, expressive pictures of girls in love.

The rest of the books I examined were from the later 1940s. In 1947 Edition du Grand-Chenes produced an edition of Bilitis illustrated with nine lithographs by Andre Dignimont. One thousand were printed, on velin blanc; the paper was very white and smooth, not as rich feeling as some, but enhanced by red section headings at the top of each page and red page numbers at the foot, plus the drop capital letter at the start of each chapter was printed in red. The book included an introduction on the life and work of Louys written by his friend, Claude Farrère, and the plates reproduced delicate soft pencil drawings with colour shading, all pleasingly simple and attractive.

From the previous year was a curiosity, a version of Pybrac with plates by an unknown artist. It was clearly a reasonably expensive printing, as there were three different qualities of edition: one on papier d’arches that also included a ‘suite’ of the illustrations, provided in a separate folder on unbound sheets and printed on Holland van Gelder Zonen paper (this Dutch firm handmade paper from 1685 to 1982), plus two extra original designs that the editors had decided not to include in the final volume; eight copies of the book were supplied with a single extra original design and a ‘suite’ printed on velin de Renages paper (Renages is a town near Grenoble); lastly, there was the ‘basic’ printing which ran to 42 copies. The eight illustrations were the mystery- again, they spoke of quality, in that they each had a tissue paper cover. The plates were painted, perhaps in gouache, in bright colours, the scenes depicted being very explicit but (technically) rather crude. Some of these scenes also did not reflect any of the quatrains in the collection that I can can identify. The hairstyles and clothes were certainly right for the mid-’40s, but I wonder if at least some of these images were recycled from elsewhere, as if the artist, whoever he was, just decided to paint something rude that was vaguely inspired by the text- which would be odd (then again, there are those two rejected plates). An alternative explanation may be that this selection of 140 quatrains does not draw solely upon the ‘canonical’ collection of three hundred four-line verses. Louys wrote many more than those that are typically included in the available volumes (for example, the translations by Wakefield Press or Black Scat). However, it would have been difficulty to establish this with certainty from the British Library copy as a number of pages were missing. Finally, this edition appears to be so rare I can find no examples of it online- hardly surprising given that there were only ever 51 copies.

From 1948, I inspected a copy of the edition of the Manuel de civilite illustrated by Raoul Serres and ostensibly published in London. Once again, this was a ‘fine art’ edition with several levels of quality. There was just one single copy printed on luxury Vieux Japon paper with six original watercolours, six original designs by the artist and a ‘suite.’ Six were printed on handmade Auvergne paper with the watercolours and the suite; another six were on Auvergne and also included an original design as well as the suite; fifteen were on Auvergne with only the suite added and all the rest were on the velin rives paper (with a very clear watermark) but without any extras. All copies except the top quality version were initialled by the artist. Serres’ twelve watercolours are rude but very funny. The young females have little dot eyes (rather like figures by Clara Tice) and regularly sport a coloured ribbon or bow in their straw yellow hair. The older men they encounter are made to seem more ghastly and unappealing by giving them pale blue skin.

I’ve kept the (second) best for last: Suzanne Ballivet‘s 1948 edition of Roi Pausole, printed in Monte Carlo by Editions du Livre. Three levels of quality were offered: eight copies on Old Japan; forty on pur fil Johannot, a heavy paper made from 100% linen, and the remaining 925 on Grand Velin Renage (which was clearly watermarked Renage). It was a big, heavy book (29 x 23 cms) and, even though the British Library version (as always) was from the least expensive of the sets, it still felt sumptuous. It came in a hard case with card covers and a heavy paper dustjacket. There was a separate ‘suite’ of twelve of the illustrations. The book itself was illustrated by 37 lithographs incorporated into the text plus another twenty ‘tipped-in’ full page plates. Ballivet’s fine pencil illustrations were gorgeous- especially the detail of the woods and meadows in which she placed her figures, with flowers and blades of grass individually delineated. The quantity of illustrations meant there was an image every seven to ten pages, making the book feel very special indeed.

To conclude, the feel of a book- its size, the quality of the paper, the number and nature of the illustrations- all contribute to the reader’s sense that they are looking at something precious and significant. As for the plates themselves, there was unquestionably something special about seeing the luminosity of Clara Tice’s pastel colours, and the sheen of her silver and gold background, or Laurens’ jewel-like watercolours in Leda.

I wrote recently about the legacy and importance of the work of Pierre Louys: that surely can be appreciated when you handle lavish and expensive books like these and realise how much money, effort and respect publishers, artists and purchasers have been prepared to continue to put into his writings since his death a century ago. These books were unquestionably created as investments: their limited print runs and range of ‘extras’ all confirm that they were planned as highly collectible from the outset, a tribute to the high regard in which their author was held.

For more on the work of Pierre Louys, see my bibliography page. For more on my own writing on the author, see my books page with its links to my Academia page where a range of essays on Louys and his illustrators are posted.