Paul Albert Laurens (1870-1934) was a French painter and illustrator; he was the eldest son of distinguished painter Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921), who taught at the Institut de France, the Academy in Toulouse and the Academie Julian in Paris. Paul Albert was born in Paris, although the family soon afterwards moved away from the city, seeking safety during the Franco-Prussian war. Laurens’ younger brother, Jean-Pierre, was born five years later and was also a painter. Paul-Albert went to school in Paris, where he became friendly with André Gide; he studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and then, in 1890, worked at the Académie Julian alongside his brother. The next year, the young Laurens won second prize in the prestigious Prix de Rome and began exhibiting his work at the Salon des Artistes Francais during the same year. Further awards and prizes followed and Laurens became a teacher at the École Polytechnique in 1898.

Laurens and André Gide remained friends into adulthood, and they went to live for a time in Algeria. On 18th October 1893 the pair sailed from Marseille bound for Tunis, and from there travelled on to Sousse in Tunisia. In January 1894 Laurens and Gide travelled to and settled in the Algerian city of Biskra, in the former home of the White Fathers (Missionaries of Africa). Various paintings of Algerian street scenes by Laurens obviously date to this period. Through Gide, it seems almost certain that there would have been some direct contact or familiarity between Laurens and Pierre Louys, who was also a friend of the young author. The two writers had met as teenagers in 1888 and remained close until 1895, when there was a falling out. Some resemblance of acquaintance was sustained for another year until the pair severed all communication in 1896. It’s probable that all three were, to some degree, sex tourists in Algeria; Louys got some of his inspiration for Bilitis there, although for Gide the journey led to the discovery of his homosexuality. Laurens was present when Gide’s first gay experience took place, an event that made the two men close, even though Laurens (like Louys) was straight and went on to marry in 1900.

Around 1912, with his father and one of his students, Laurens helped to decorate the walls and ceilings of the Capitole in Toulouse with allegorical scenes. During the First World War, he worked with several other artists on designing camouflage schemes for the armed forces and their work served as a model for the Allied armies (the British army, for example, used the painter Solomon J Solomon to work on tank camouflage). After the war, Laurens was promoted to Professor of Drawing at the École Polytechnique, where he continued to teach until his death in 1934. His professional standing was recognised when he was appointed member of the French Academy of Fine Arts in 1933.

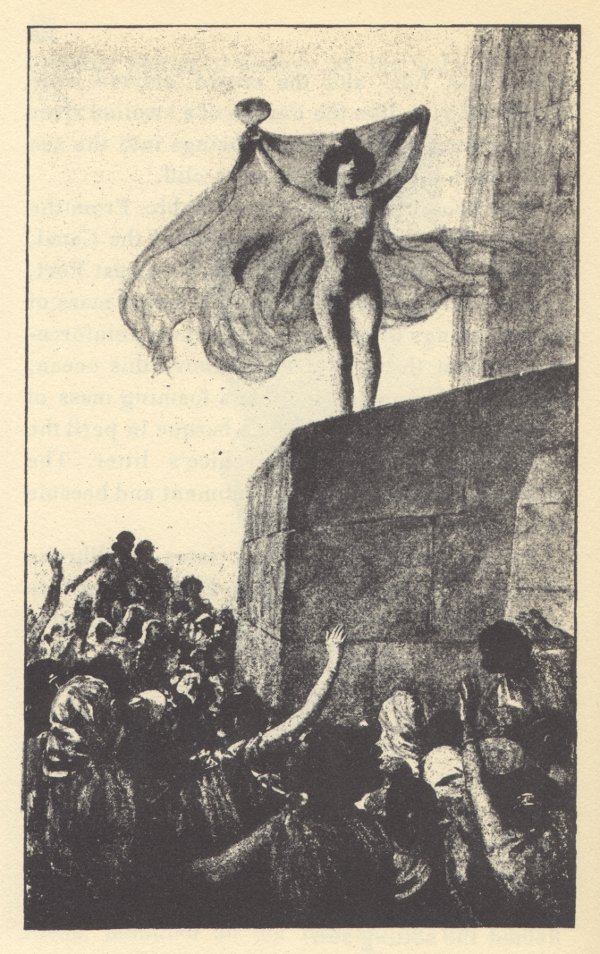

Laurens is known for his portraiture (for example, of Gide) and for his illustrative work. He also designed posters for theatres and, as a painter, his output appears extremely eclectic: he doesn’t seem to have had any really settled style or subject matter. Doubtless he painted what he was commissioned to produce or what would sell. Hence we have the neo-classical bathing scene, Les Baigneuses, which looks very like work by Alma Tadema, Lord Leighton and many others, a mythical Feast of Flora, and an imitation of the eighteenth century galant painting of Watteau in Le Jardin de l’amour (The Garden of Love).

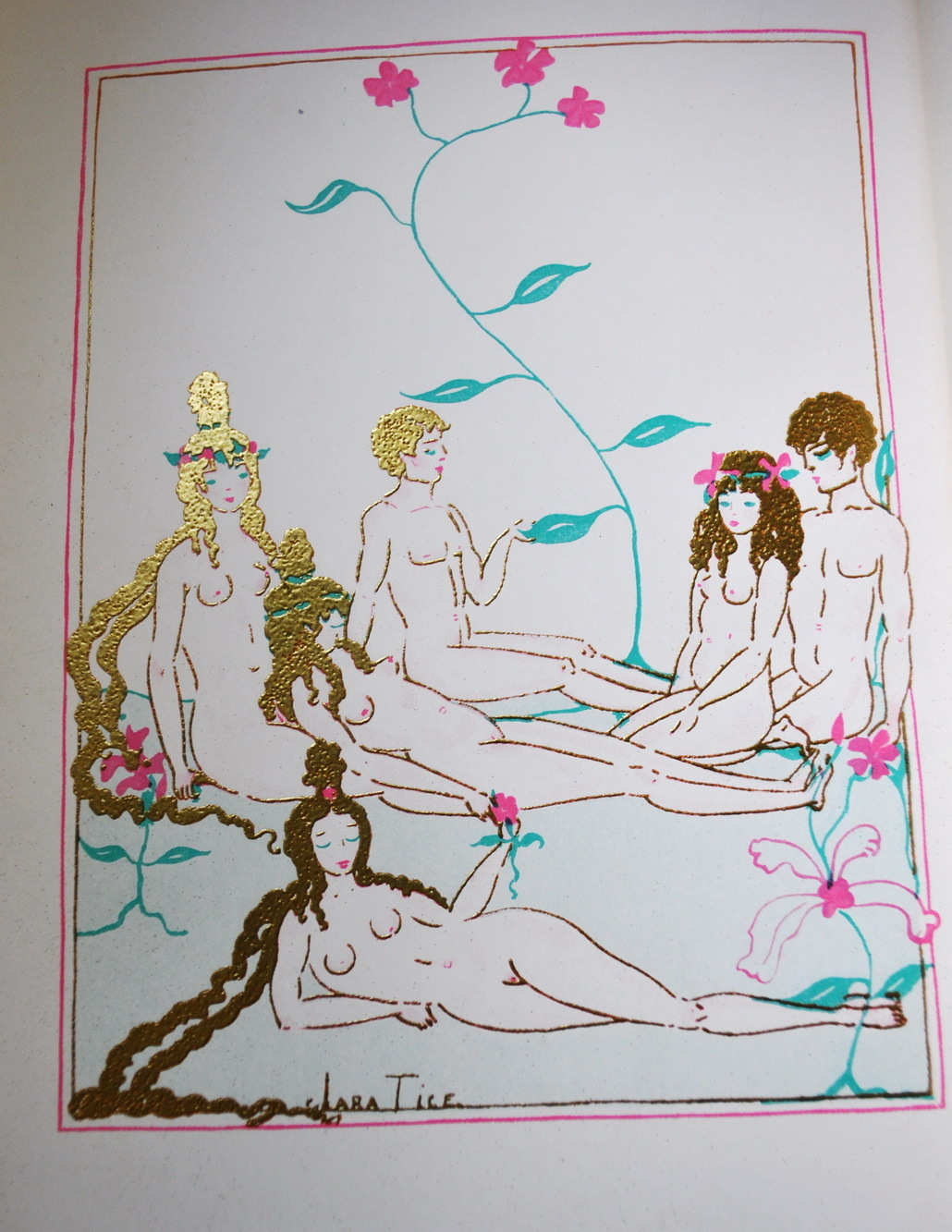

Neo-classical nymphs and nudes are rather common, as might be anticipated if one is familiar with Laurens’ work on Pierre Louys retelling of Leda. These female figures draw on the artist’s skills as learned in the life drawing classes at the Academy, and are more or less conventional, reflecting the types developed by Bouguereau or Chabanel, but we can see as well that Laurens liked to depict pairs of nubile figures, leaving the viewer a little unsure as to whether he is seeing friends, sisters, mother and daughter or lovers.

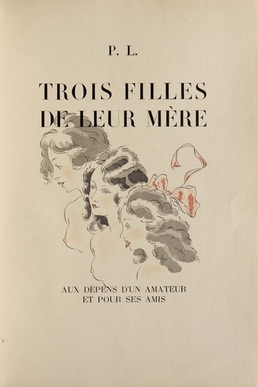

Amongst his other sources of income, Laurens illustrated books. He provided plates for editions of Daudet and Gautier, but also worked on editions of three books by Pierre Louys- in 1897 he produced six etchings depicting scenes from the recently published Aphrodite and, in the following year, he illustrated editions of the novel Bilitis and the short story Leda, as I have described previously.

For me, Laurens’ work on the three books by Louys seems to rise above his other designs: there’s an energy and creativeness in them which I don’t find in some of his more generic pieces. Perhaps the subject matter was especially conducive to his imagination- as we might judge from his life study titled Adolescence (below), a figure who could as easily be a nereid, dryad or character from one of Louys’ Hellenic fantasies. Viewed from this perspective of this work, Laurens’ young nymphs may be understood as being clearly symbolic of the fertility of Nature, of perpetual renewal and regrowth. Nevertheless, aside from any mythological connotations, Lauren’s interest in this transitional state from youth to maturity was by no means unique to him: it was an aspect of life that fascinated very many artists of this period, from famous figures such as Edvard Munch (Puberty, 1894-95) and Oskar Kokoschka to relatively less well-known painters like Eleni Luksch-Makovsky (Adolescentia, 1903), Oskar Heller, Paul Hermann Wagner and Richard Muller. More particularly, a range of artists of the same period were drawn to create studies of the sleeping adolescent: examples include Marie Madeleine Rignot-Dubaux (1857-87), Oskar Heller (1870-1938), Hugh Ramsay (1877-1906), Gustave Brisgand (1867-1944) and, especially, Zinaida Serebriakova (1884-1967), a Russian artist who settled in France in 1924 and who, between 1923 and 1935, painted a number of portraits of her daughter, Katyusha, asleep in poses very similar to that chosen by Laurens.

Mike Cockrill has also pointed out something I had initially missed- the resemblance of Laurens’ model’s pose to that of numerous paintings by Balthus. The reclining female figure was one to which he returned throughout his career: it began with Therese Blanchard with one leg raised in Girl with Cat (1938) and evolved from there. Variations upon the theme of the slumbering girl include The Victim (1939-46), Reclining Nude (1945), The Week with Four Thursdays (1949), Nude with Cat (or Basin) (1948-50), The Room (1952-54), Large Composition with Raven and Nude with Guitar (both 1983-86) and Expectation (1995). All of these postdate Laurens’ death; although I have been unable so far to date Adolescence, Balthus may have been inspired by it- or will certainly have been responding to the general popularity of the subject within French painting of the era.