Here, I’m going to test out an argument that the illustration of works of literature may be regarded as a form of translation- from one medium of communication to another. I’d like to propose that, whether the passage is from one language to another, or from the word on the page to the line, the same considerations and difficulties can apply.

Translation is by no means the neutral process that we might suppose it to be. We can all achieve instant AI translations now, at the click of the mouse, but we would be mistaken in accepting these too readily. This may change as AI becomes more intelligent, but- at present- it reflects the choices made by the individuals who created the tools- the very same process of selection made by human translators working directly from a text- but perhaps neither so intelligently or expertly in the case of AI.

I have written a lot about the work of the Belgian born and French speaking novelist and poet Pierre Louys (1870-1925) and (as I mention on another page) I have had cause in my research to translate several works by him that are currently not available in convenient English editions. Now, I’ll admit, I generally run these through an online translation tool to begin with; it’s quick and it almost instantly gives you a basic text to work with. But what you get always needs tidying up. As we know, words can have several meanings and it is not unusual for online translators to choose the commonest- or perhaps the standard- definition, something that can reduce a sentence to nonsense. To restore what I consider to be the correct sense, of course, I’ve got to make another subjective selection. Slang is often poorly handled by translation tools- especially if it’s from a century ago. Then there are fundamental linguistic differences that have to be resolved: French, for example, often uses the present tense to discuss past events, something which sounds odd in English. Grammar and style have to be sorted out to make a passage easily readable and, all the time, there is an almost unconscious input from the person doing the transcription- preferred ways of saying things; words you’d rather not use (at all or in certain contexts)- a whole constellation of taste and prejudice which can get involved. Then, of course, there’s the question of verse. Do you aim to preserve the meaning, and produce blank verse, or do you try to reproduce something of the metre and rhyme pattern too, which can force you into quite major divergences from the literal sense of the text? This is especially an issue with Pierre Louys, who took a delight in matching the verse forms of classical literature with very rude content. Part of the parody is the contradiction between the sonnet form and the smut. Which do you choose?

In short, a translated work can only be the author’s words filtered through a third party’s well-intentioned, principled and carefully considered prejudices and selections. Perhaps, then, this is an argument for saying that illustrations are a more neutral form of translation, as the illustrator only has to represent what he or she has read. However, as I’ve pointed out several times before, selection and taste always intervene. The artist has to decide: which character(s) or which moment to depict; the manner of that depiction; the general artistic style employed (to choose extremes- a ‘photo-real’ illustration, or something very free and impressionistic?) Once again, all sorts of issues of taste and choice intervene- probably further shaped by a publisher’s editorial policies, house style, target market and so on. Illustration is no less neutral than verbal translation.

So, I turn again to various translations of Pierre Louys’ Chansons de Bilitis, and to wonder whether the 1945 edition illustrated by Maurice Julhès (1896-1986) was one of the most effective combinations of words and image in the long history of publication of this work.

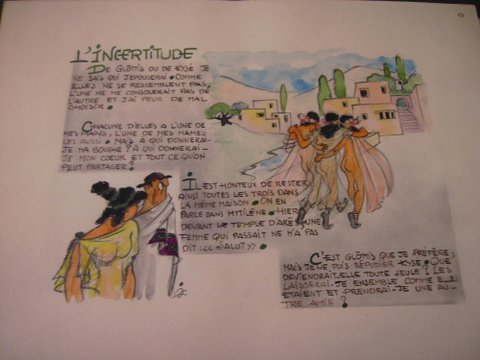

Julhès was born in Sannois, in the Oise valley, and trained in the decorative arts before becoming an illustrator for humorous newspapers after 1918. During World War II, Julhès worked for several magazines that were under German supervision and, as a result, after the Liberation, he was suspended from his work for two years. However, in 1947 he returned to illustrating comic strips and children’s books. Despite his primarily satirical and mocking output, he was commissioned to illustrate adult works such as the Poésies of Sappho or the Fleurs du Mal by Baudelaire- as well as his work on Bilitis. Coming to the work as a cartoonist on this text, Julhès took care to reflect the Greek setting and brought his skills in capturing vivid and concise imagery, as well as the ability to weave the text around the pictures in a dynamic way.

In 1999, I might add, a graphic novel version of Aphrodite by Pierre Louys also appeared. The three parts of the book were published as separate volumes with different illustrators; Milo Manara illustrated Book 1, Georges Bess worked on Part 2 and Claire Wendling on Part 3. The books feature lavish full-page colour plates. Other contemporary graphic novel style approaches to the novels of Louys have been mentioned before: Georges Pichard‘s work on the novella Trois filles de leur mere in 1980 and Kris de Roover‘s illustration of the unfinished L’Histoire du Roi Gonzalve in 1990. All these editions (as well as the older ones) will be found to be readily available through Abe Books and Amazon.

My last examples purport to be translations but are actually pornographic pirates of Les Chansons. In 1930 Les Veritables Chansons de Bilitis appeared, a work (probably) of Pascal Pia (1903-79). Born Pierre Durand, he was a French writer, journalist, illustrator and scholar; he used a number of pseudonyms, including Pascal Rose, Pascal Fely and others. In 1922 Pia published the erotic work Les Princesses de Cythère (Cythera being the island of Aphrodite) and followed this up in 1928 with La Muse en rut (The Muse in Heat), a collection of erotic poems. His ‘pastiche’ of Bilitis fits within this genre of writing and perhaps reflects his sense of humour (often expressed in absurdist tendencies).

Two illustrated versions of Les Veritables Chansons followed, the first with plates by Lucien Metivet (1863-1932) a poster artist, cartoonist, illustrator and author. The text purports to be a new translation of a Justinian manuscript. If this refers to the Roman emperor Justinian (482-565 CE) we are looking at a time period some 900 years after the purported dates of the ‘original’ Bilitis in the book by Louys. The new version is in prose, not verse, and takes various incidents from the original by Louys and expands upon them in detail, going far beyond what the Songs either say or imagine. Hence we have, for instance, a detailed description of Bilitis and Glottis having sex together and a later episode in which Bilitis and Mnasidika decide to enter into a menage a trois with an innocent girl called Galatee. My guess is that this name was borrowed from a character Louys’ Aventures du Roi Pausole, which Metivet coincidentally had also illustrated in 1906. Metivet’s illustrations are in his trade mark red and black ink and reflect the explicit contents of the new version of the story.

A further edition of the Veritables Chansons appeared in 1946, illustrated by Jean Jouy. This was a further pirating of the original, in the sense that the prose passages from the 1937 version were rendered into verse and matched with large colour plates. The book has moved a long way from what Louys wrote, as there is a large heterosexual element, as well as mixed orgies, both in the text and the images. Jouy’s plates are very attractive, but highly explicit. There is also an undated edition entitled Les Chansons Secrets de Bilitis with illustrations by an unknown artist which are very similar in form and content to Jouy’s.

These last two examples are not ‘translations’ as such, but they illustrate how editors and writers adapting the texts of others can depart from the originals they’re working to create almost wholly new books. To return to my thesis at the start, I think it’s not uncommon for readers to take illustrations in books rather for granted but, when done well and thoughtfully, they can be as much part of the visual and intellectual experience as the text itself.

[…] were asked to work on the very adult Chansons de Bilitis. As I suggested in another recent post, I assume that their facility with combining text and image- and their ability to create an image […]

LikeLike

[…] which were decorated in a style clearly of the first decade of the twentieth century. Lucien Metivet, whose illustrations of Louys have been mentioned before, also worked on a version of Pausole in […]

LikeLike

[…] previously discussed how the illustration of texts can, arguably, be a form of translation of those books; in my […]

LikeLike

[…] appeared in 1980. In all these cases, the illustrators were faithful after their own style to the text they were commissioned to work upon, meaning that in most cases the plates are not really suitable […]

LikeLike

[…] to visual form whilst the erotic content had an instant appeal to buyers. As I’ve argued before, the illustrated editions of Pierre Louys’ various books constitute a major literary corpus that […]

LikeLike