In 1862 Gustave Flaubert published his historical epic, Salammbo. His publishers suggested having the book illustrated, given that it featured spectacular scenes of warfare and exotic religion in ancient Carthage, but the author rejected the idea, objecting that it would destroy the imaginative impact of his work. I think we can understand and sympathise with Flaubert as a writer; additionally, much of Salammbo is taken up with almost cinematic descriptions of vast armies fighting- something illustrations could hardly have represented adequately.

Nevertheless, I was fascinated to discover this detail about the book and to contrast it to the attitude of the later author, Pierre Louys, whose Aphrodite was, I would say, strongly influenced by Salammbo. Both books are set in an alien, pagan world, distant in time and space. Both feature thefts from temples, crucifixion of offenders, sacred harlots and an enigmatic central female figure. Despite these broad thematic similarities, Louys’ novel pursued a very different course and, significantly for our purposes here, illustrated editions appeared very soon after its first publication.

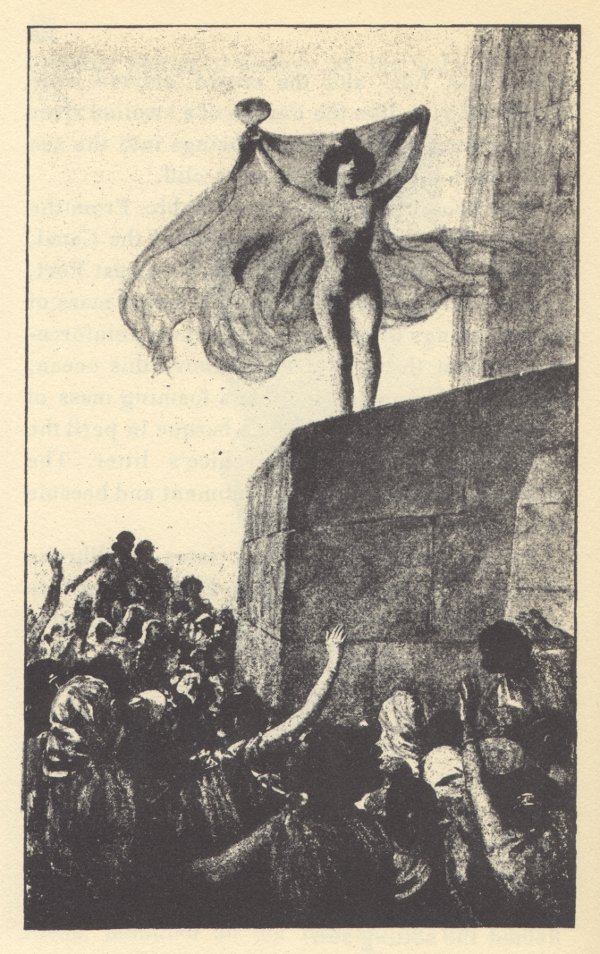

Considering this contrast, it struck me that Pierre Louys was, in fact, a very visual writer. He was himself a photographer and an amateur artist and in recent years his erotic photos and drawings of naked women and girls have been published, as Le cul de femme and La femme respectively. His books contain scenes that seem almost intended to form the basis of plates designed by artists: Princess Aline admiring herself before her mirror in Roi Pausole, or, in Aphrodite, the heroine Chrysis carried off as a girl by horsemen or displaying herself to the population of Alexandria in the jewellery she has had stolen for her. For this crime, she is executed with poison, and the artist Demetrios, who became obsessed with her, then sculpts her deceased body as a way of preserving an image of her notable beauty. In the novella Trois filles de leur mere (Three daughters and their mother), the eldest daughter Charlotte is imagined dressed up as a schoolgirl with plaits; in the Twilight of the Nymphs, Louys pictures how the nymph Leda’s body and hair are all different shades of blue. As for most of Louys’ later poetry, it is comprised of short verses (for example the compact four line ‘quatrains’ of Pybrac that each describe a single vignette) which are ideally suited to the artist and have been copiously illustrated as a result.

These verbal images soon became printed ones. Twilight of the Nymphs was published with illustrations by Paul-Albert Laurens in 1898. In that same year, Laurens also illustrated the second edition of Bilitis. Others editions of that book followed in 1895, with watercolours by Robaglia and in 1906, illustrated by Raphael Collin. The first illustrated edition of Aphrodite, with plates by Antoine Calbet, appeared in 1896; another, illustrated by Edward Zier, appeared in 1900 (this is the edition to be found on Gutenburg). In that same year, the sculptor Joseph Carlier exhibited Le Miroir, which represents Chrysis admiring herself in a mirror, at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Plainly, Louys must have welcomed the physical depiction of his imagined scenes. Another edition appeared in 1896, reprinted in 1898 and 1910, with plates by Edmond Malassis. As I shall describe elsewhere, Malassis’ plates and headpieces partook very much of the graphic style of their period, but they also exude a charming and saucy energy, taking full advantage of the opportunities offered by the text to make the most of the set-pieces, such as the bacchanalian orgy at the home of the courtesan Bacchis (Book 3, chapters 1-4).

We can go further still, I think. Louys often included scenes in his books in which performances are staged for characters- and thereby for the reader. He imagines this play or dance and then enacts it for us as if we are the audience too. These performances involve the characters, but in addition they are something for us to witness as a spectacle and to become deeply engaged by. In Les aventures du Roi Pausole, Princess Aline falls in love with the dancer Mirabelle when she sees her performing on stage. In Bilitis the two young girls, Glottis and Kyse, dance for Bilitis, partly displaying their skill but also as a way of trying to tempt her to choose one as a partner- a moment depicted in a plate by Paul-Emile Becat. In the novella Trois filles de leur mere, the story concludes with the three daughters staging a ‘play’ (with costumes) for the young student they have all seduced. This is very clearly a ‘home theatrical,’ but there are other elements in the story in which the girls and their mother perform for others. The oldest daughter, Charlotte, passed various milestones in her journey to sexual maturity in front of invited audiences, whilst the entire family, as sex workers, in a sense ‘perform’ for their clients in order to give them an illusion of passion and love.

Staged scenes therefore seem to have been a key part of the way in which Louys liked to envisage his works. That this is the case is demonstrated, as I described before, by the fact that he collaborated or agreed to several works being turned into various musical dramas, operas and plays. Fascinatingly, a very early (and brief) erotic film, Le Rêveil de Chrysis (1899), seems to have been based upon the opening chapter of Aphrodite. Much more recently, La femme et la pantin became a film, firstly in 1935 as The Devil Is a Woman, directed and photographed by Josef von Sternberg, starring Marlene Dietrich, and then in 1977 as That Obscure Object of Desire directed by Luis Buñuel. Aphrodite in 1982 was filmed by Robert Fuest and, very much more loosely, David Hamilton adapted Les Chansons de Bilitis into the 1977 film Bilitis.

Because Louys’ books were so frequently illustrated, especially in the quarter century period from his death until about 1950, it is now hard to hard to conceive them separately from those images- rather as is the case with John Tenniel’s illustrations of the Alice stories. Those book pates can stand apart as separate artworks (and, as I have described, there is a thriving market for them as such) but they also bring vitality and vividness to the texts themselves. Often, they shed new perspectives on the books. For example, whilst Louis Berthomme Saint-Andre‘s watercolours for Trois filles de leur mere are quite delicate and make the sex scenes appear almost loke genteel parties in suburban living rooms, Georges Pichard‘s cartoon style artwork, with its strong contrasts between black and white and bold delineation, brings out far more starkly and memorably the bleaker, more depraved aspects of the book. This is a key aspect of illustration: encapsulating literary ideas in visual form, can mean that they are far less mediated or disguised. As such, they may reveal the psyche of an age more directly, crystallising or laying bare attitudes and appetites which were generally hidden.

The best book plates not only complement but enhance and amplify the text that they accompany. The result is a Gesamtkunstwerk, a single, unified work of art, and I would argue that many of the illustrated Louys volumes should be regarded as such (as, once again, the auction prices paid for them by collectors might well attest). It’s arguable, as well, that the publication record of the works of Pierre Louys stand testimony to the fact that word and image can work so well together: there have been at least forty illustrated editions of the poet and author’s works over the last 130 years.

For more detail on the illustrators of Louys, see my books page.

[…] to working for private press erotic publications. Berque’s drawings for the erotic works of Pierre Louys are prominent amongst these, such as the 1945 edition of Trois filles de leur mère which did not […]

LikeLike

[…] more contemporary authors were writing poetry and ‘modern classics’ (Apollinaire or Pierre Louys for example). Individuals like Carlo, who provided illustrations for spanking novels, don’t […]

LikeLike

[…] and to be able to find an expression of these and of his/her own responses. As I have suggested before, when this is done perceptively and well, the result lifts the entire artwork. It’s […]

LikeLike

[…] stood Collot in very good stead for approaching his subsequent commissions, working on the works of Pierre Louys. Successively, Collot illustrated the poet’s erotic Biblical parody Aux temps de juges […]

LikeLike

[…] poor working females, especially actresses and dancers, well suited him to working on the work of Pierre Louys. Brouet first began to receive commissions to undertake erotic illustrations in the mid-1920s. […]

LikeLike

[…] illustration commissions included working on various erotic books, which included several works by Pierre Louys. Amongst the titles Vertès illustrated were La Semaine Secrete de Venus, 1926, which was written […]

LikeLike

[…] of the family Louys described. These radically contrasted illustrative strategies underline my argument that the contribution of the artist to illustrated books can have a major impact upon the […]

LikeLike

[…] have posted previously about the close connection between the writing of Pierre Louys and the art associated with that. I […]

LikeLike

[…] editing of their work (frequently unconscious, no doubt) accentuates this. As I have observed several times before, their departures from the text will inevitably shape the reader’s perceptions […]

LikeLike

[…] the catalogue explaining the how and why of the canvas. Nevertheless, we see again how text and image may combine and complement to create a greater […]

LikeLike

[…] illustrator only has to represent what he or so she has read. However, as I’ve pointed out several times before, selection and taste always intervene. The artist has to decide: which character(s) […]

LikeLike

[…] word combined reinforce each other. Hence my interest in the illustrated editions of the works of Pierre Louys in particular, and a broader interest in the partnership and interplay between art and literature […]

LikeLike

[…] and interior designer (a practitioner of the idea of the gesamtkunstwerk I’ve mentioned before). As well as private clients, his work was commissioned by the royal family and to hang in public […]

LikeLike

[…] physical book itself underlines some of what I’ve said several times previously about the qualities of limited edition fine art printings and how they can interact with the […]

LikeLike