The illustrated novels of Pierre Louys are instructive in many ways. Primarily, of course, they reveal evolving artistic responses to the author’s prose and verse, thereby not just illustrating his personal vision but demonstrating- indirectly- what book purchasers were understood to want, and what publishers and their commissioned artists believed they could offer them, within the parameters of law and public decency. In other words, the nature of illustrations can be a record of changes in society- in attitudes to sexuality, gender and the status and rights of women.

Louys’ first books appeared in the last decade of the nineteenth century, notably Les Chansons de Bilitis in 1894 and Aphrodite in 1896. The earliest illustrated editions are distinctly reflective of their era, tacitly articulating contemporary attitudes towards the female gender and the position of women in society. Librairie Borel‘s 1899 edition of Aphrodite, illustrated by Antoine Calbet, is a case in point: his depictions of Chrysis reflect the Academic tradition of life studies, derived from the classical artistic tradition since the Renaissance, and the young Galilean courtesan is depicted very much in the style of Greek statues of Aphrodite and paintings of Venus by Botticelli, Tiziano Vecelli and others thereafter.

Likewise, when Georges Rochegrosse provided plates for an edition of Ariadne in 1904, what he supplied was a very revealing reflection of the period’s conceptions of bacchantes- frenzied women. In the plate illustrated below, they are seen wreathed in ivy and flowers and leopard skin, about to tear apart the helpless Ariadne. Elsewhere in the same volume, Greek ladies were presented as sedate, respectable, elegant, graceful and beautiful- as in the illustration that accompanied the preamble to The House on the Nile by Paul Gervais, which is seen at the head of this post.

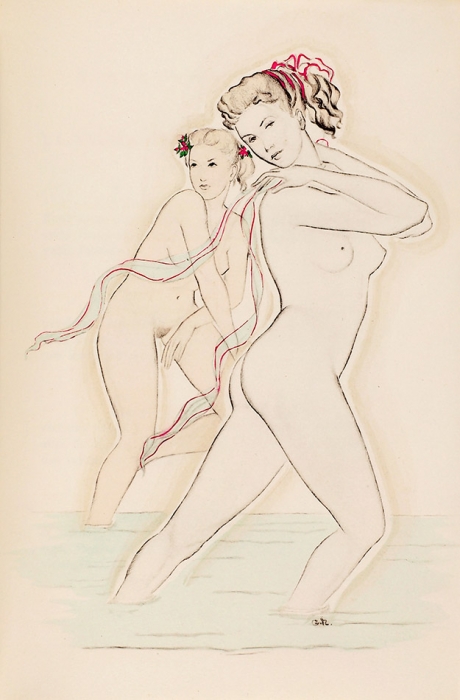

As I have described in other posts, numerous further illustrated editions of the various books written by Louys were to follow, both before and after his decease in 1925. A constant feature of these was women in greater or lesser states of undress, plates that faithfully responded to the text but also very consciously appealed to the primarily male collectors of fine art limited editions of books. Amongst these many examples, the most interesting are probably those designed by women. Those volumes worked on by Suzanne Ballivet, Mariette Lydis and Clara Tice are notable for the quality of their work and for the fact that the latter two were lesbian and brought their own sense of eroticism to their reactions to the texts. So, for example, in her plates for the 1934 edition of Les Chansons de Bilitis, Lydis’ vision of female lovers was far more intimate and subtly sensual than most of the works produced by male contemporaries- such as J A Bresval (see below). Other women who worked on the various titles by Louys included Renee Ringel (Aphrodite, 1944), Yna Majeska (Psyche, 1928), Guily Joffrin (Psyche, 1972) and editions of Bilitis illustrated by Jeanne Mammen, Genia Minache (1950), Carola Andries (1962) and Monique Rouver (1967). The frequency with which female illustrators were employed as the century passed is noticeable, although I hesitate to identify a distinctly feminine style.

Post-war, new editions of Louys introduced us to new conceptions of his female characters. J. A. Bresval illustrated an edition of Bilitis in 1957, his figures being very much inspired by contemporary film stars like Gina Lollobrigida and Brigitte Bardot. The women have a dark-haired fulsomeness typical of the period; the eroticism is rather cliched, such as the frontispiece to the book, which shows Bilitis with a lover: the latter kneels before her partner, embracing her waist and kissing her stomach; the standing woman cups her breasts in her hands and throws back her head in a highly stereotypical soft-porn rendering of female ecstasy.

However, by 1961 and Raymond Brenot’s watercolours for a new edition of Sanguines, we see a new aesthetic of the female body beginning to emerge: the bosoms may be just as fantastical, but there is a slenderness and, in some of the clothes, a sense of a more liberated and relaxed mood. Pierre-Laurent (Raymond) Brenot (1913-98) was a painter who was also very much in demand to design record sleeves, advertisements and fashion plates (for such couturiers as Dior, Balenciaga, Ricci and Lanvin). More tellingly, he is known as the ‘father of the French pin-up’- consider, for example, his advert for lingerie manufacturer Jessos- “Comme maman, je porte un Jessos” declares a young teen with pigtails, seated with her blouse unbuttoned to reveal her bra (“just like my mum’s”); I have discussed this style of marketing in another post. Brenot’s poster designs, for consumer goods, holiday destinations and films and theatres, regularly featured glamorous young women and, when this work declined during the later 1960s, he returned to painting, producing many young female nudes.

What has to be observed, though, is that most of the nudity portrayed by Brenot was not justified by the actual stories in Sanguines. There are some naked slaves in The Wearer of Purple (see below), and Callisto in A New Sensation does share a bed with the narrator, but most of the rest of the stories are really quite respectable and sex-free (by the standards of Louys), being more concerned with psychology than sexuality. What we see, therefore, is evidence for the tendency to treat the works of Louys as a platform for erotic illustration. Frequently, this was a distinct element in the author’s stories, but it seems that he had acquired a reputation for sexiness which was then applied more liberally, presumably in the knowledge that the name would sell. The same criticism can, in truth, be made of Georges Rochegrosse’s depiction of the bacchae in the 1904 edition of Ariadne (see earlier): what he depicted might perhaps be implied in the text, but what Louys wrote doesn’t wholly warrant the nudity that we see:

“They wore fox skins tied over their left shoulders. Their hands waved tree branches and shook garlands of ivy. Their hair was so heavy with flowers that their necks bent backwards; the folds of their breasts streamed with sweat, the reflections on their thighs were setting suns, and their howls were speckled with drool.”

Ariadne, c.2

The men who feature in Brenot’s illustrations often seem hesitant, ill at ease or, even, embarrassed at being discovered with the women in their company- his take on the ‘satyrs’ with nymph in a scene from ‘The Wearer of Purple’ is a case in point. In Louys’ story, this is an incident involving a slave girl being assaulted by two other servants so as to create a titillating composition for the the artist Parrhasius to paint. As we can see in the reproduction below, the satyrs appear afraid of the young woman, having lost all their accustomed priapism, whilst she strikes me as indifferent to their presence and in fully control of the situation. Given Brenot’s later output, it’s almost certainly overstating things to say that these plates reflect shifts in social attitudes.

Coming right up to date, the 1999 edition of Aphrodite demonstrates how visions of women may have developed and advanced (or not). The book was issued in three volumes, the first two being illustrated by two male comic book artists, Milo Manara and Georges Bess respectively. Both have distinctly erotic styles and the results strike me as being, in essence, highly accomplished and artistic reproductions of glamour photography and lesbian porn; for example, George Bess’ picture of the reclining woman, which faces the start of Book 2, chapter 1 of the story, seems to me to be drawn in a style very much influenced by Mucha or Georges du Feure: the streaming hair and the encroaching, twisting foliage all have the hallmarks of Art Nouveau (which is of course highly appropriate given the publication date of the original book). In the modern version, Chrysis is regularly depicted in intimate scenes alone, with her maid Djala or with the two girls Rhodis and Myrtocleia. With their tousled hair, pouting lips and pneumatic breasts, these women are very much the late twentieth century ideal. Most of the time, they are presented as being more interested in each other than in any of the male characters in the story, but my response is that there are really rather high-quality examples of fairly standard pornographic obsessions. When we look at them, it’s worth recalling Pierre Louys’ own description of his heroine, when he wrote to the painter Albert Besnard asking to paint her:

“Chrysis, as womanly as possible- tall, not skinny, a very ‘beautiful girl.’ Nothing vague or elusive in the forms. All parts of her body have their own expression, apart from their participation in the beauty of the whole. Hair golden brown, almost Venetian; very lively and eventful, not at all like a river. Of primary importance in the type of Chrysis, the mouth having all the appetites, thick and moist- but interesting […] Painted lips, nipples and nails. Depilated armpits. Twenty years old; but twenty years in Africa.”

A fascinating contrast to the the first two volumes of the 1999 edition is to be found in the third, illustrated by Claire Wendling (born 1967). She is a French author of comic books and her response to the text is interesting because it is so much darker and less obviously ‘sexy’ than that of her male collaborators. The plates are, literally, dark in tone and, although they tend to focus on solo female nudes, rather than lascivious eroticism is there is a mood of mental and physical suffering entirely appropriate to the final section of the book, in which Chrysis is arrested, sentenced to death, executed and buried. Her cover image evokes- for me- thoughts of Gustav Klimt in its decoration, but the twisted, crouched posture of the woman doesn’t look seductive- rather she’s supplicatory or, possibly, predatory.

At the start of this post I proposed that the book illustrations published with successive editions of the works of Pierre Louys can be a record of changes in society- in attitudes to sexuality, gender and the status and rights of women. I think that this is true, but that the evidence does not necessarily reveal huge steps forward in those areas. Far more women are involved now in commercial art, and the works of Louys provide vehicles for the expression of lesbian desire on their own terms: albeit in the service of illustrating books written by a man in which his sympathetic views of same-sex attraction compete with heterosexual masculine eroticism. Art styles have evolved, but the attitudes expressed by what’s depicted have not necessarily developed at the same pace.