There are two versions of the poem Maddalou by Pierre Louys. The first is included amongst a collection of ‘Fourteen Images’ in the second volume of the poet’s Complete Works. It follows the lyrics of Bilitis, indicating that it dates to same period, around 1894.

“Her hair is black; her skin is brown. Around her chest she wears a white rag, which was once a camisole, and which reveals her half-naked.

A red rag serves as her skirt, a rag with more holes than a battle flag. And that’s all.- she doesn’t have a shirt; her feet are bare as hands.

But what embroidered silk would be more beautiful than this colourful costume of human skin and rags? What jewel purer than the point of her breast?

She moves in the light, without shame and almost without clothing, while I follow the play of shadow and sunlight around her form.”

The second Maddalou, as I have noted before, is a longer poem, published separately after Louys’ death in 1925. I have been able to see a copy of the 1927 edition, held by the British Library, and- because it’s such a rare little book- I’ve reproduced a translation of the French prose poem here.

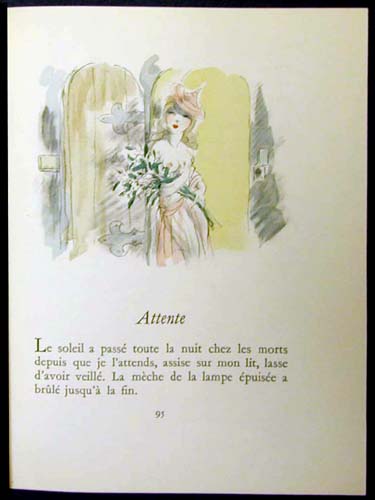

The physical book itself underlines some of what I’ve said several times previously about the qualities of limited edition fine art printings and how they can interact with the experience of reading the text. As was common practice at the time, the book was issued in a limited run of 400 copies, printed on three grades of paper. The BL copy is number 36 and is on the ‘cheapest’ paper, Velin d’Arches. This is a strong cotton paper, with a fine grain and ‘deckle’ (untrimmed) edges. It has weight and a pleasing grained texture. The book itself comes in a card case that opens to reveal the forty loose pages; these are quite small- called in-huit in French, they’re only about 19 cms tall. It was a delight to see and handle and Edouard Degaine’s illustrations were gorgeous- soft-focus and evocative.

“At the end of the long path which winds between the bushes, I discovered a hovel in the middle of a small garden. It was a poor shack that no one knew, far from hamlets, far from the roads. Never has a tourist, a hunter or a passer-by walked there. It had only one window and just one door. Through the window I saw an old woman seated and, before the door, a young girl was standing. But this young girl was very strange, with rags like a savage and a body so beautiful that I felt myself go pale.

Throughout the day I thought about her and, in the evening, I went back. She came towards me, little by little, curious, but also slightly on her guard, like a tame doe.

‘Who do you want here? My grandmother isn’t at home. Grandma’s left for the town, for the Saturday market. I’m alone- who are you looking for?

I’ll be on my own for another three days. If you want a basket, grandma has taken to them all to sell at the market. You’ll quickly catch up with her on the road running beside the sea.

Why don’t you reply? Why are you just looking at me without saying a word? I haven’t got anything… Only a bowl of milk… and some figs… and water from the spring.

How did they come to live here? She didn’t know anymore: she was little; it was ten or more years ago. Back then, there, one of the men who’d loved her mother had killed her.

Back there, on the other side of the mountains. That was the day when Maddalou was taken away by her grandmother, passing through so many villages. She doesn’t know anything more than that, neither can she read, nor count, nor say where she comes from.

The hovel didn’t belong to them. They are allowed to stay there as an act of charity. By whom? A lady whom they never see, whose name she’s forgotten- but who owns all the land round here.

She responds to me with her head lowered and, when she stops speaking, I no longer even hear the silent footsteps of her bare feet in the dust.

Maddalou, with such black hair, barely covers herself with a red rag which, pierced, torn, slashed, wraps over her chest, and hangs down to her slender heels. She puts this on like a shirt, passing her arms through the tears, then ties it in the middle of her body. It gapes on the side and opens on the thigh- and her feet are bare.

But what silk would dress her better than this motley costume of brown skin and rags? What could be more beautiful than this exposed hip? What jewel could be purer than the tip of her bare breast?

She moves in the light, without shame and almost without clothing, and each of her gestures reveals all her contours to the play of shadow and sun.

‘Oh yes! Yes, stay here with me. I’m alone, I’m miserable. No-one ever comes here, except the seabirds and the birds from the woods. Stay! I’m all alone and I’m bored. I hate to go to work in the fields with my little coat all in rags. The gleaners have all got shoes and they mock my bare feet.

Instead, I go to the deserted willow grove, to harvest the stems. I come back and I weave baskets; I milk the black goats; I sing to myself- and yet, I’m not happy. You’re the first man I’ve seen- the first since… since I’ve been grown up and since I’ve been crying at night without knowing why.

I love life in my rags. I wash them like lace; when I see spots there, I just cut them out and make more holes for the wind to blow through. The holes dress me with my skin; the material covers what it can. If someone were to lie in wait for me in the woods… but no one spies on me in the woods and doesn’t follow me along the path.

On more than one evening, do you want to know how I make my way back from the fountain? With my rags over my arms, completely naked so I can run faster!

Now I’ve told you all my secrets- I’m tired of telling them to myself. I never like the flower I put in my hair, because it was me that gave it to myself.’

The hovel is just a large room covered with a broken roof. Just as Maddalou’s rags tear and show her body, so the roof has holes in and lets you look up at the sky. It lets in the wind and the rain, butterflies and dead leaves, the bats and the birds and, in their turn, the sunshine and the moonlight.

There’s neither a table nor chairs. You sit yourself on empty baskets and you eat off your lap. The bucket, the spindle whorl and the pan hang on the mossy, decaying wall. The goats sleep in one corner, the old woman by the chimney, the mice in the wall, the blue parrot on the rack and the girl under the stairs.

Under an old broken staircase that serves as a perch for the hens and from which she hangs a cloth as a curtain, there Maddalou has her bed. On a mattress of seaweed and tow sleeps the loveliest girl in the world. It’s just a sack laid on the earth, made from lots of saffron bags sewn together with string and somewhat gnawed by rats. A roll of rags serves as her pillow. She only has one sheet: the thin red canvas that she wears as a dress during the day. At night, when she lies down, she’s uncovered down to her feet, her head resting on her hand.

But those who did not see her on this regal bed, half-opening her mouth and stretching out her arms, will die without having known what human splendour can be.”

Maddalou is a very different poem to almost everything else produced by Pierre Louys (and hence nearly every book I’ve described on this blog). It describes a tender, romantic love, which despite the evident impact that the young woman’s partial and unconscious nakedness has on the male narrator, is taken no further. It’s not even clear whether the narrator expresses his admiration for the titular heroine, or just worships her silently. Degaine’s full page illustrations do tend to focus on the naked Maddalou, but the headpieces at the beginning of each section of the prose poem are small landscape scenes, evoking the peaceful, deserted natural world in which the hovel is set.

There are some hints of adult sexuality- and of the potential dangers of the outside world- but Maddalou and her grandmother inhabit a kind of Edenic utopia cut off from the harsh outside world. Their contact with it seems to be limited to selling the baskets at market- something the grandmother undertakes in order (it seems) to protect the girl from the corruption and temptation of the rest of society. There are indications that the maturing young woman is beginning to sense a lack in her life (her loneliness and her tears), and wants more, but she doesn’t yet know what that is.

The encounter between narrator and female household echoes the mise en scene of Trois Filles de leur mere, but the story is otherwise located in a completely different universe. Whether we are even in contemporary France is unclear (although the amphora in Degaine’s frontispiece might suggest not). All in all, the closest parallel in the rest of Louys’ work to this poem is the Dialogue at Sunset, found in Sanguines, which is set in ancient Greece and in which a goatherd and a girl meet, talk and fall in love. That said, Maddalou’s name implies very strongly that the setting is French: as we know from Bilitis and Aphrodite amongst other books, Louys was perfectly capable of coming up with authentic Greek names from the sources he knew so well. Wherever the story takes place, though, Maddalou’s world is innocent, pure and placid and, as the final sentence reveals, it’s held up to us as a model to envy and to imitate.

A longer, fully annotated version of this essay can be downloaded from my Academia page.