I have quite arbitrarily set the cut-off point for the most recent illustrations of Les Chansons de Bilitis by Pierre Louys at 1950, not because there was any radical change in style or representation at this date, but because it set apart a convenient number of artists and images for a single post. As readers will see, there’s certainly no real hint of any modern movements in the illustrations; the work of the Argentinian Raul Soldi, whom I allocated to the ‘classicists,’ was as avant-garde as anything that was published. He incorporated a distinct surreal element into some of his images, but his output was actually so variable that it was hard to categorise him.

The rather obscure French painter Jacques Daniel (1920-2011) was commissioned to work on a 1957 edition of Les Chansons. His plates (see example at head of page) are presented in a style that seems to be uniquely his own (and which doesn’t resemble any of his paintings either). They appear to have been formed by laying down a background of pencil or charcoal and then creating the design by erasing the figures’ outlines. The images are unusual, but necessarily quite simple. They are essentially life studies with very little characterisation.

A few years earlier, in 1954, Gaston Barret was commissioned to provide illustrations for another edition of Louys book. Barret (1910-91) was a French painter, engraver, watercolourist and illustrator. He’s known for his atmospheric (even austere) landscapes, characterised by mists and desolation, but he undertook the illustration of about fifty books, including Guy de la Maupassant’s Le Maison Tellier (1966), The False Mistress by Honoré de Balzac and other texts by Francois Carco, Tolstoy, Alphonse Daudet, La Fontaine, Marcel Pagnol, Sade, Saint-Exupery, and Virgil.

In 1951 Barret provided illustrations for the erotic writer Pierre Mac Orlan’s Les Dés pipés ou Fanny Hill, in 1950 for Collette’s L’ingénue libertine and in 1973 for her Claudine en menage. In 1953 he illustrated La Vie Privée du Maréchal duc de Richelieu, by Louis François Armand, duc de Plessis. Maupassant’s Maison Tellier (1881) is set in a brothel in Normandy and Barret also designed a series of ink and watercolour scenes entitled Le Maison Close (a publicly licenced brothel). All of these titles are erotica, with plates to match, which makes it easy to appreciate why Barret was employed to work on the notorious book by Louys. His colour plates are delicate and attractive and they were pretty faithful to the detail of the text, although relatively discrete, as we see in the bed scene where well-positioned sheets and flowers preserve the lovers’ modesty. The image of Bilitis in the tree (see above) is a subject I have discussed previously.

Monique Rouver, meanwhile, is an artist about whom I have been unable to find any detail, other than she illustrated a number of books in the 1960s and ’70s. Her plates for a 1969 edition of Bilitis exude a powerful female sensuality; her figures seem strong and self-possessed, evocative for me of the work of Mariette Lydis in their erotic depiction of female lovers.

Carola Andries (1911-89) was a German painter who worked in a variety of styles, including abstract canvases as well as more conventional still lifes and landscapes. The twelve watercolours she supplied for a 1962 German translation of Louys, Die lieder der Bilitis, are attractive and highly impressionistic. The Belgian sculptor Eugene Dodeigne was also commissioned to supply some etchings of naked bodies for a further edition of Die lieder, which was published in 1963.

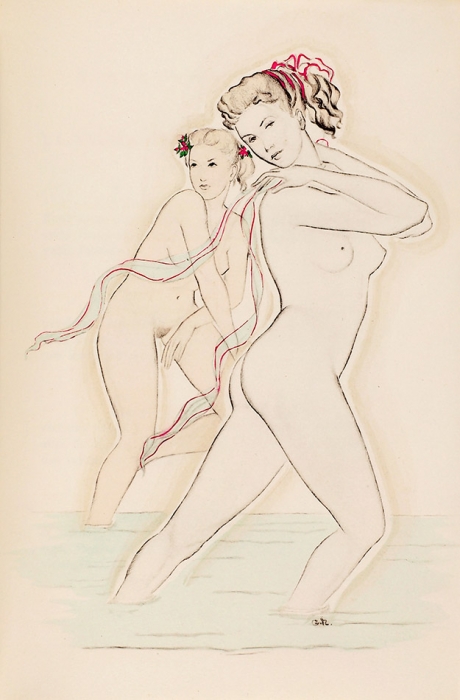

By way of contrast with the work of Andries, there are the plates designed by Genia Minache for a 1950 edition of Les Chansons. Genia Hadji-Minache (1907-72) was born Evgenia Semenovna in St. Petersburg and, after the Russian Revolution, her family evacuated with the White Army to Istanbul. Thence, they moved on to Prague and then Paris. During the 1930s, Minache studied at the Ecole Nationale des Arts Decoratifs, where she got to know other émigré artists, with whom she participated in group exhibitions at the prestigious Galerie Bernheim by 1934 and the Galerie Zak (a collection of works by Russian artists) in 1936. In 1934 she married Savely Khadzi (hence the Hadji surname in French) and moved to Czechoslovakia, but returned before the outbreak of war.

Her first solo exhibition was held in 1949. Many of her later works are endowed with a poetic, sensual Orientalism, in which she emphasised the exotic and erotic; she paid particular attention to rich fabrics as well as delicately rendering human flesh and hair. Minache painted mainly in gouache and watercolour, and considered herself a successor to the school of St. Petersburg Art Nouveau. She was also regularly commissioned to illustrate books, such as the Kama Sutra and Diderot’s Les Bijoux indiscrets (1969). Given her skill and interest in nudes, she was an obvious person to work on Bilitis.

Where Andries was loose and free, Minache was precise and- as a result- far more erotic. Her lovely, lyrical lines capture the passion and desire of the book perfectly: the plate Mer de Kypris (Sea of Cypris) accompanies a verse that describes the aftermath of a rite to Aphrodite celebrated by a thousand maenads, an event that has been (implicitly) an ecstatic lesbian orgy. L’Etranger (The Stranger) accompanies a song addressed to a man visiting a brothel (no.135):

“Stranger, go no further in the town. You’ll not find younger or more expert girls at any other place besides my own. I am Sostrata, known beyond the sea. See this one whose eyes are green as water on the grass. You do not wish her? Here are other eyes, black as the violet and hair three cubits long. I have some better still. Xantho, open your dress. Stranger, her breasts are firm as quinces, touch them. And her lovely belly, you can see, bears the three Kyprian folds. I bought her with her sister, who is not yet quite old enough for love, but who is her useful helper. By the two goddesses! you are of noble blood. Phyllis and Xantho, follow the gentleman!”

Like Barret, Minache was pretty faithful to the text upon which she worked and her lovely plates are a true complement to them.

Lastly, J. A. Bresval’s sixteen 1957 illustrations of the Songs perhaps stray into pin-up porn. I have been unable to find any other details of this artist (not even his full first name) but his busty girls look like rather crude pin-ups and his frontispiece to the book shows Bilitis pantingly fondling her own bosom as her lover kisses her stomach, in the rather cliched manner of glamour photos. It’s certainly effectively erotic, if not great art. That said, his posing nude for the poem Effort (below) is actually quite effective when you appreciate that it accompanies a verse describing how Bilitis sleeps with a girl called Gyrinno in an act of revenge after being deserted by her wife, Mnadisika. In the song Attempt, Bilitis confesses that she knew Gyrinno had been attracted to her- and now she has given in. The song Effort reads as follows:

“More! enough of sighing and stretching out your arms! Begin again! Or do you think that love is relaxation? Gyrinno, it is a task, and by far the most severe. Awaken! You must not go to sleep! What matters to me your purple eyelids and the streak of pain which burns your slender legs. Astarte boils and bubbles in my loins. We went to bed before twilight. Here already is the wicked dawn; but I am not so easily fatigued. I shall not sleep before the second night. I shall not sleep: you must not go to sleep. Ah! how bitter is the taste of dawn! Gyrinno, judge of it! Kisses are more difficult, but stranger, longer, slow…”

The next song, To Gyrinno, makes this poor girl’s unhappy situation clear: “Do not think that I have loved you. I have eaten you like a ripe fig, and drunk you like a draught of burning water… I have amused myself with you… but already I no longer know your name, you who have lain within my arms like the shade of another loved one.”

Bresval went on to supply similar buxom blondes for an edition of Le Chevalier De Parny’s Poesies Erotiques in 1958.

As I’ve frequently said before, the interaction of plate and page can have a profound impact on the overall feel of a work. Some illustrations- such as Carola Andries’ watercolours- are pretty but they don’t lift the text particularly. Bresval’s soft porn perhaps detracts and distracts from the poetry of Pierre Louys, whereas I feel that Barret and Minache made far more significant contributions to the editions they designed.

[…] was illustrated during the period of the late 1920s through to the late 1940s. A separate post deals with artists’ interpretations after 1950. Louys died in 1925, and there was a […]

LikeLike

[…] a little explored gallery of genres and individual styles- as I’ve indicated in my posts on Bilitis and […]

LikeLike

[…] 1928), Guily Joffrin (Psyche, 1972) and editions of Bilitis illustrated by Jeanne Mammen, Genia Minache (1950), Carola Andries (1962) and Monique Rouver (1967). The frequency with which female […]

LikeLike