During the last decade and a half of his career, Pierre Louys completed three major works- the Handbook of Manners for Young Ladies, which was a parody of deportment manuals; the novel Trois Filles de leur mere, and the poetry collection Pybrac. It is arguable, in fact, Pybrac was never actually completed, in the sense that Louys added continually to the quatrains that comprise it and the published versions of the book only include a fraction of the total known number of verses. There were, in addition, several unfinished works: the novels Toinon and L’Histoire du Roi Gonzalve and the mock-travelogue/ novel L’Ile aux dames. These texts all have a number of themes in common: Louys’ encyclopaedic literary knowledge coupled with a tendency to mock those books; his filthy sense of humour; the utopian strand to his writing, and his liking for erotica.

Here, I focus on Trois Filles de leur mere (Three Daughters of Their Mother), arguably one of the most difficult books by Louys. This considerable difficulty for readers arises from the tension between the surface content of the text- some of his obscenest erotica- and the deeper purposes of his writing.

Louys had a number of aims and targets in writing Trois Filles. He felt a deep antipathy for the stifling morals and conventions of the Catholic church within which he’d been raised (hence his regular recreations of the pagan faith of classical Greek and Roman seen in several of his works) and it’s clear that the book is, in part, an assault upon many of the sacraments and concepts of the faith: the story features sex in a church, a vicious parody of communion, and a perverse immaculate conception, for example. One of the three daughters, Charlotte, is something of a martyr-figure, and it’s even arguable, I think, that the mother, Teresa, stands as a satanic temptress figure for her trinity of girls. Amongst the other targets for Louys’ derision, alongside casual piety, were French wine snobbery and the general bourgeois mood of propriety.

In addition, the book is deeply literary. There are repeated references to classical and Renaissance and later French authors, such as Clement Marot (1496-1544) or La Fontaine, which readers are expected, implicitly, to know. Some of these sources are quoted, some are parodied and mocked. An obscene passage is attributed to the Humanist scholar Erasmus, which I’m sure he never wrote (although I’ll confess I’ve not checked all 86 volumes of his collected works). One contemporary French writer is condemned as merely deadly dull (just as was the case with the moralist Guy du Faur in Pybrac): after a rather overstimulating session with the mother, Teresa, the student narrator concludes “I took from my library a ‘heady’ novel by Henri Bourdeaux that I had purchased especially for the purpose of calming myself down when I was in a worked-up state.” Bourdeaux (1870-1963) was a lawyer and author known for his traditional Catholic morality and his very correct French style.

Besides citing classical authors, Louys borrowed themes from them just as he modelled parts of his plot on the Bible. Hence, we find traces of Leda, Pasiphae and Europa in some of the incidents described.

The book is also ‘metatextual’ before that term was invented. It is repeatedly aware that it is a story, pretending to be a memoire. For example, the student narrator addresses us, as readers, explaining “I would have taken much more pleasure in inventing a story where I could give myself (so easily) a more sympathetic role” or “That’s the trouble with memoires: they get monotonous. In a novel, this kind of repetition can never be excused, but in life it has to be accepted.” When a play is acted out in the final chapters of the book, the artificiality of that make-believe within the wider pretence of the story-telling is continually highlighted, the use of dramatic jargon constantly reminding us that it is all invented and staged: for example “Teresa probably did not know that she had introduced a prosopopoeia into her speech, but there is no need to know the figures of rhetoric to put them… at the service of persuasion. Was it the apostrophe, the hypothesis, the exhortation or the prosopopoeia that won? I do not know…” Very evidently, this sort of passage is not part of standard work of pornography.

The text can be understood at several levels simultaneously, I would argue. The basic plot concerns a student who moves into a new flat next door to Teresa and her three daughters and discovers that all four are sex workers. A few weeks of uninhibited sensual indulgence with the entire family follows, before they suddenly disappear. The novel may be interpreted as a condemnation of the sex trade and its malign impact upon the women trapped within it. At the same time, though, there are elements of the narrative which celebrate female sexual autonomy and women’s right to control over their bodies and their pleasures. Teresa is proud of her physical prowess; she comes over as a powerful and determined woman- except that the downside of her assertiveness is the fact that she dominates her family and is involved in damaging incestuous relationships with all of them. Then again- as he often did- Louys seems to suggest that self-sufficient lesbian households may represent some sort of social utopia– an ideal of independence and happiness. Yet he also interrogates lesbian or bisexual identity, perhaps ultimately tending towards a position that sexual fluidity is a more accurate way of understanding individuals.

On its face, Trois Filles may appear outrageously, shockingly pornographic, but I think it’s plain that any text that casually mentions Jesuit preacher Louis Bourdaloue, Roman poet Tibullus, the Greek playwright Aeschylus, Alexander the Great, Melisandre, and the painter Ingres, has depths and intentions that are not instantly obvious. The complex and multi-faceted nature of Trois Filles means that we are constantly left unbalanced by it, not quite sure of Louys’ meaning, uncertain whether he is playing a game and always returning to the text to uncover new layers of significance.

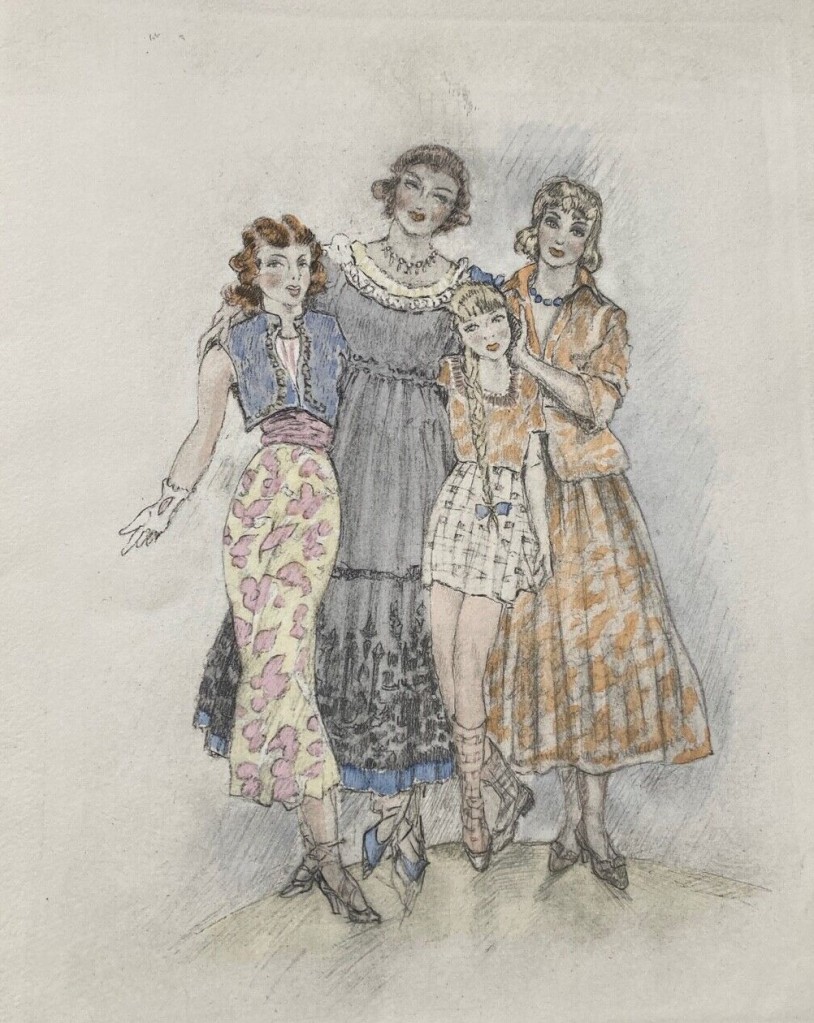

As ever, I find the novel’s bibliology as fascinating as the book itself. Illustrated editions proved extremely popular with publishers and several artists whom we’ve already encountered before, because of their work on texts by Louys, were commissioned to provide imagery. The first edition of Trois Filles was released by Pascal Pia in 1926, with twenty plates by Louis Berthomme Saint-Andre. Further illustrated editions followed in due course: in 1930, with plates by Andre Collot; in 1935, illustrated with sixteen etchings by Marcel Vertes and in 1936, with 34 watercolours by René Ranson (1891-1977). Ranson was one of the most important designers at work during the interwar heyday of the Parisian music hall, working for the Folies Bergère between 1924 and 1932. Renowned for his draughtsmanship, he was a painter, illustrator and costume designer as well. Ranson also supplied designs to the Paris Opera, and for several film studios, including Fox, Pathé and Paramount. Over and above his theatrical work, Ranson painted glamour or pin-up nudes and provided plates for works such as Baudelaire’s Fleur du mal. In past posts I’ve remarked on the frequency with which cartoonists and caricaturists found work as illustrators- and, for that matter, how often the skills acquired in illustrating children’s books might be transferred to the distinctly adult content of the works of Pierre Louys. René Ranson demonstrates how theatrical and costume designers might find additional work in book illustration; other examples I’ve noted previously include George Barbier, Louis Touchagues and Andre Dignimont. All of them surely deserve our respect for their multi-talented ability to turn their hands to almost any artistic commission offered to them.

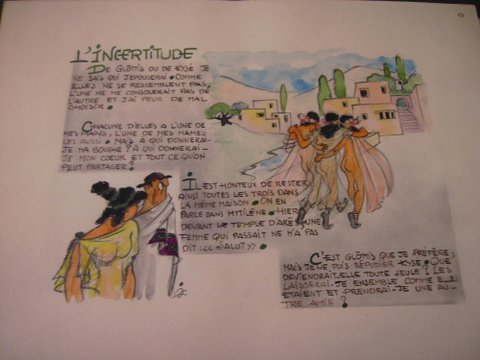

After the end of the Second World War, further editions of Trois Filles followed: Jean Berque provided sixteen plates for an issue in 1955 and, late that same year, Edouard Chimot also illustrated an edition with a dozen plates (see head of page for the family in their best ‘New Look’ dresses). Then, in 1960, an edition illustrated by Rojan was published. Finally, as I have mentioned several times, a version illustrated by graphic novel artist Georges Pichard appeared in 1980. In all these cases, the illustrators were faithful after their own style to the text they were commissioned to work upon, meaning that in most cases the plates are not really suitable for publication on WordPress. This explicitness can- as I’ve suggested- have its own implications for the text that the images accompany. Pichard, used to multiple frames in cartoon strips, designed an impressive fifty-three plates to go with Louys’ book. The sheer number of these, coupled with his graphic style of strongly drawn images, has the effect of underlining the more bleak and depraved aspects of the book. His monochrome plates emphasise the elements of tragedy and desperation in the narrative- something that Chimot’s and Ranson’s very pretty coloured illustrations definitely do not do.

This post is a simplified version of a longer, fully annotated essay on the novel that can be downloaded from my Academia page. I have also written there in detail on Louys’ attitudes towards religion. For readers who are interested, several translations of the book are readily available, the most recent being Her Three Daughters, available from Black Scat books (published December 2022). See as well my Louys bibliography and details of my other writing on the author.