I have written at length on the books and poetry of Pierre Louys- and the illustrated editions of those works. It is fair for readers to ask why? What is this little known writer’s significance? Here, I shall try to justify that.

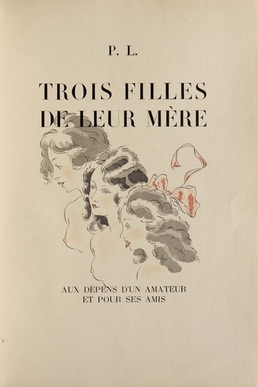

In literary terms, in his time, Louys was a best selling author and an influence on André Gide, Paul Valéry, Oscar Wilde, and Stephane Mallarmé; moreover, the other French authors regarded him at the time as a writer of major significance. However, it has been said that these writers came to overshadow that of their mentor and friend. The Encyclopaedia Britannica suggests that “Louÿs’ popularity, which rested more on his eroticism than on purely aesthetic grounds, has faded.” I hesitate fully to endorse this statement, as the most erotic of Pierre Louys work only emerged after his death when his unpublished and unknown manuscripts began to emerge. Before that, works like Pausole, Bilitis, Aphrodite, Crepuscule des nymphes and La femme et le pantin, whilst having some ‘adult’ passages, were also rightly extolled for their purely literary merits- and still deserve a readership for that reason today.

In his time, the fact that he wrote Les Chansons de Bilitis and was friendly with and supportive of the lesbian writer Natalie Clifford Barney was significant for helping a distinctively lesbian artistic culture to first emerge. The book itself gave its name in 1955 to the Daughters of Bilitis, one of the first lesbian organisations campaigning for civil and political rights in the USA. Now, whilst it is fair to admit that a stereotypical heterosexist male fascination with female same-sex relationships plays an undoubted role in the composition of Bilitis and other works, there was more to it than that. As professor of French Tama Lea Engelking has observed, both Louys and Barney “looked toward ancient Greece for a model of how open-minded and tolerant she wished society would be… [they were] both enthralled by the hedonistic sensuality they associate with Hellenism in contrast to Christianity’s disdain for the body.” Each of these writers were somewhat ahead of their times in their views. In the case of Louys, his liking for eroticism and his tendency to seek to provoke can deflect from his message; by employing the medium of erotica to convey challenging concepts, he risks alienating audiences who do not see beyond his parodies and jokey filth to the serious social philosophy beyond. Louys’ views on diversity and tolerance remain valid.

As I have described previously, a number of Louys books formed the basis for musical works, such as Debussy’s songs based upon Les Chansons de Bilitis or the plays and operas based upon Aphrodite and La Femme et le pantin. The latter novel also translated to film, directed by Josef von Sternberg in 1935 and Bunuel in 1977. In 1933, Alexis Granowsky made a feature film based on Roi Pausole. In that same posting, I illustrated the sculpture of Aphrodite that Louys’ friend Rodin created for the staging of the play based upon the author’s second novel. Many of my postings have examined the graphic art impact of Louys.

Book Illustration

To repeat what I have emphasised before: the sixteen different published works of Louys have generated nearly 150 different editions, illustrated by over one hundred artists. When we appreciate that there are only four illustrated versions of Apollinaire, twenty-one editions of various works by Paul Verlaine and a roughly similar number of editions of de Sade, we begin to appreciate what a significant body of books this represents. It is testament (of course) to interest in the writings of Louys, but it is indisputably a major source of evidence on the evolution in graphic styles over the last century and a quarter.

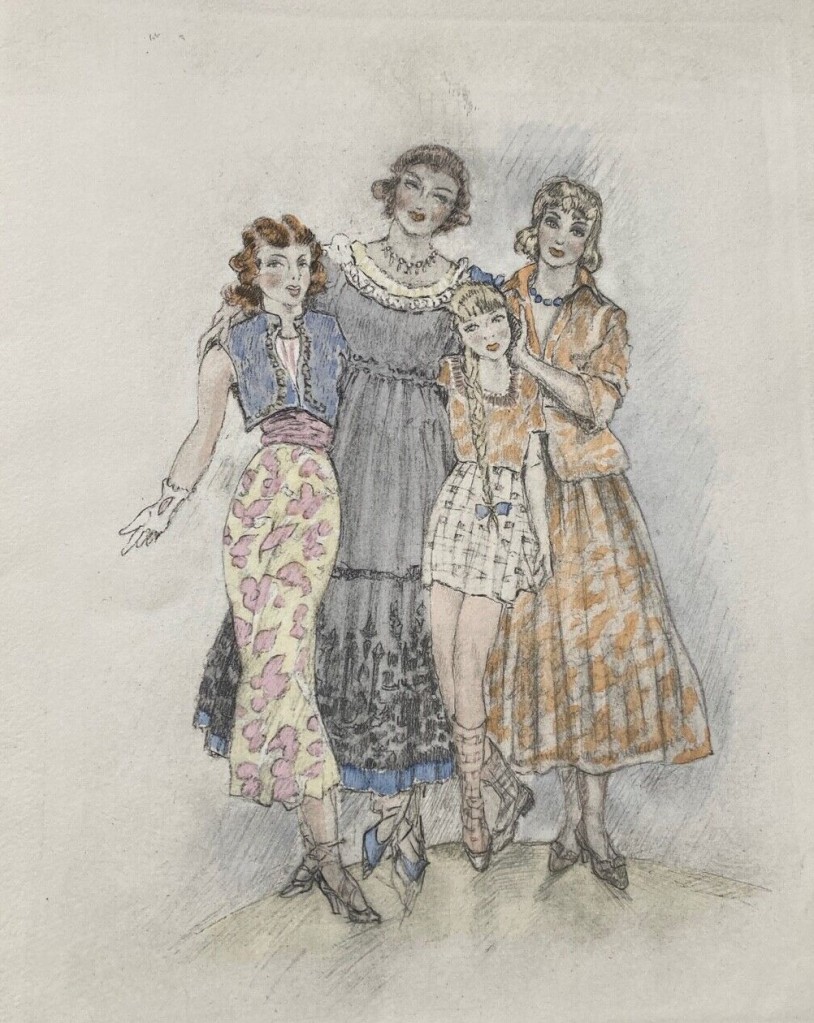

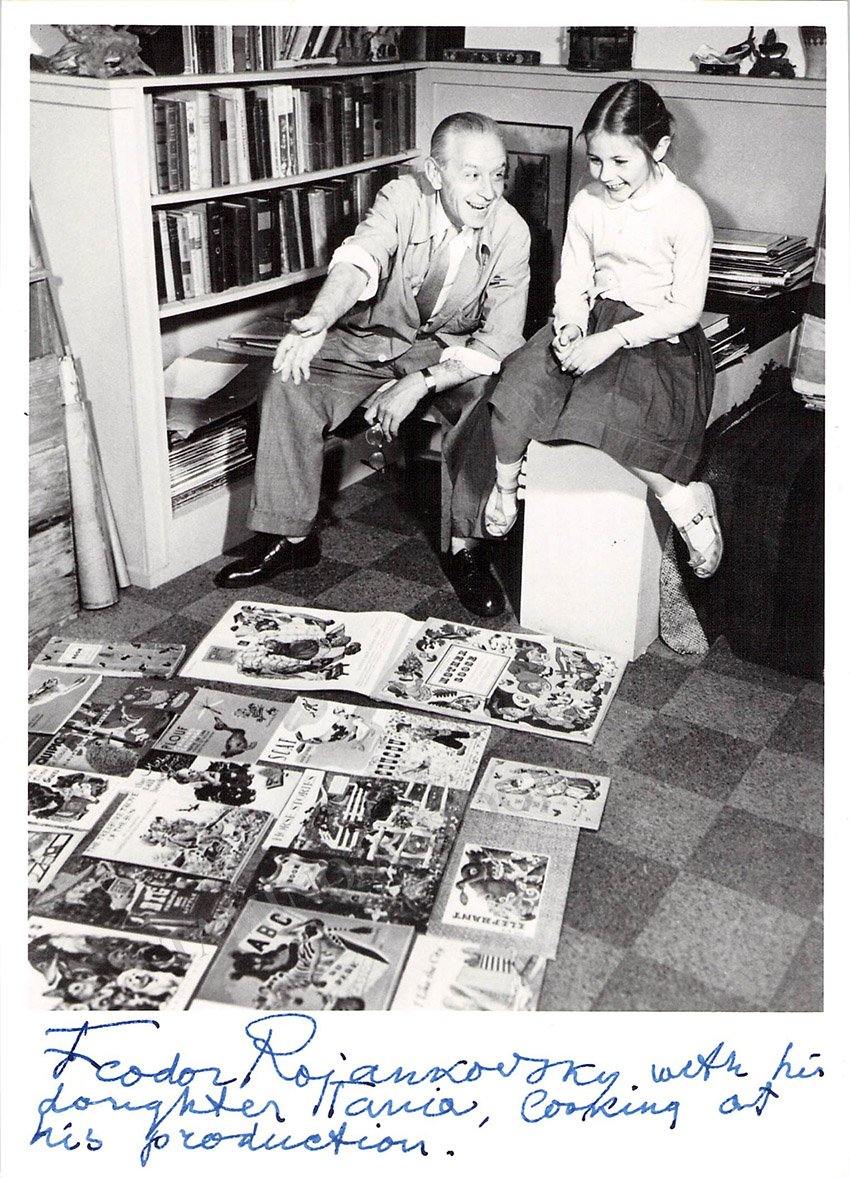

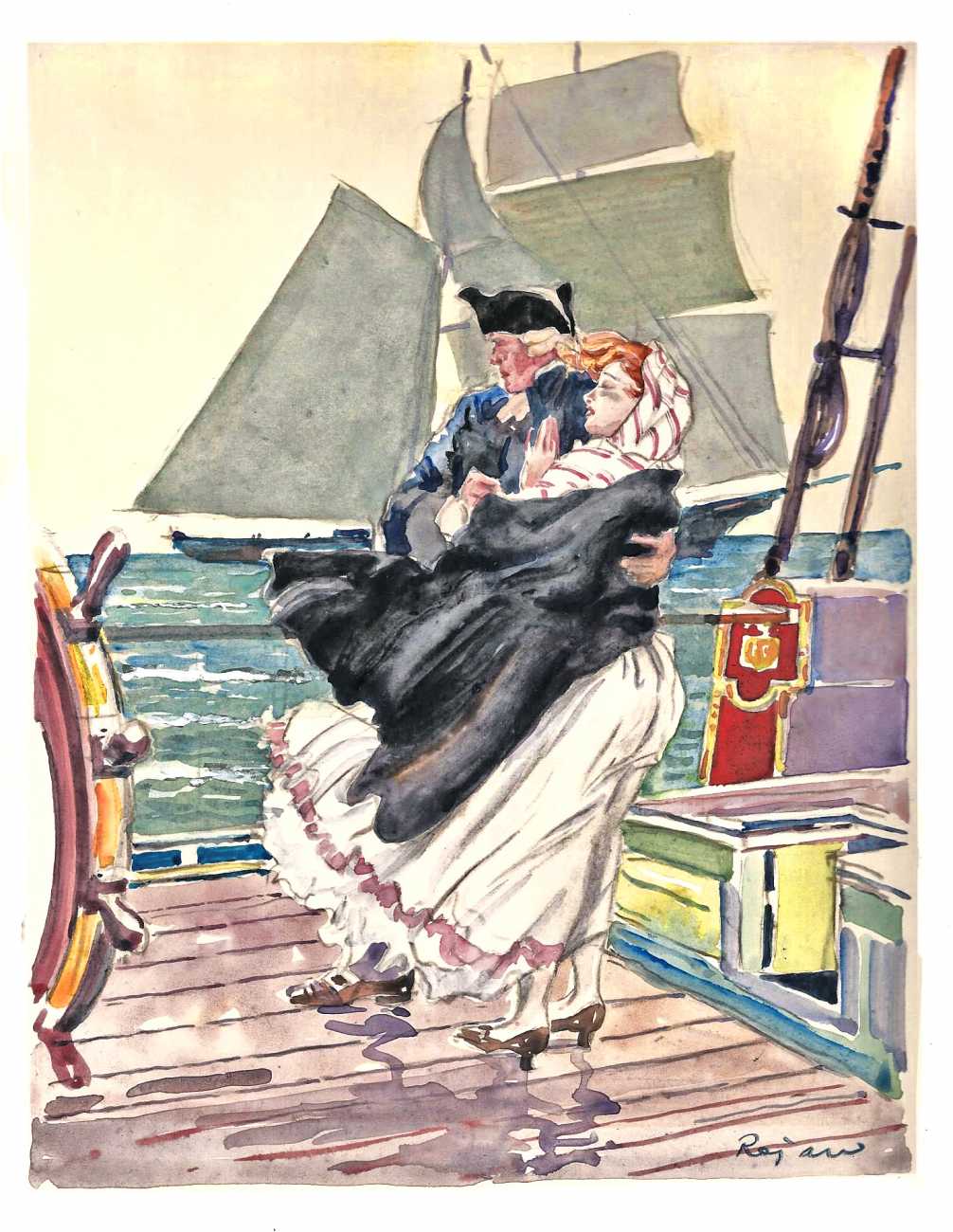

Some artists may be especially defined through their work on volumes of Louys’ prose and poetry. Leading examples include Mariette Lydis, who worked on five editions of his books; Edouard Chimot likewise illustrated five different titles, whilst Paul-Emile Becat, Marcel Vertes and Louis Berthomme Saint-Andre all illustrated four different works. Amongst those who illustrated three works by Louys are Andre Collot and Rojan. The art generated in response to Louys’ writing was significant at the time in terms of what it told us about aesthetic developments and the public’s literary and artistic tastes (and, therefore, about deeper cultural developments). It remains of importance today: there is still considerable and active interest in these illustrated volumes, as evidenced by the regular sales of Louys’ books by auction houses such Christies, Sotheby’s, Bonhams and Drouot in Paris.

Painters

The artistic inspiration of Louys extended beyond book plates, as I have mentioned previously. Jules Pascin painted a scene from Roi Pausole and Paul Albert Laurens designed a set of etchings of Aphrodite that were not destined for an actual edition of the book. In 1942, the American painter Stanton Macdonald-Wright (1890-1973) painted a Homage to Pierre Louys– the picture was recently sold by Bonhams- the canvas was reused three years later for another picture, hence its rather odd appearance at the back of the frame of the second work.

It is Les Chansons de Bilitis which has had the greatest artistic impact of all Louys writings. I have described before how British photographer David Hamilton very freely adapted the book into a film and a photo album. From a date soon after the book’s publication, in fact, the story was a source of inspiration for visual artists. The Symbolist Lucien Levy-Dhurmer (1865-1953) drew a beautiful pastel image of Bilitis as early as 1900. Others that have been equally inspired include George Auriol (1863–1938), who was a poet, songwriter, graphic designer, type designer and Art Nouveau artist. He created illustrations for the covers of magazines, books, and sheet music; these include a floral cover and a wonderful Japanese print inspired portrait of Bilitis. Secondly, just like Levy-Dhurmer, the Polish painter Stanisław Eleszkiewicz (1900-63)- who had lived in Paris since 1923- was inspired to create a study of Bilitis and a lover (presumably Mnasidika).

Erté designed a series of costumes for a production of Les Rois des Légendes (Legendary Kings) at La Marche a l’Etiole Femina Theatre, Paris, in 1919, one of which represented a jocular Roi Pausole in flamboyant Middle Eastern/ Babylonian robes. The photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue also took a series of photographs on set at the filming of “The Adventures of King Pausole” on the Cote d’Azur in 1932, a production for which he was assistant director. The French sculptor and painter Theo Tobiasse (1927-2012) in 2011 created a bronze sculpture based on the story.

Conclusions

Louys continues to have a cultural impact. In July 1988, in Rome, the premiere took place of Aphrodite (which described itself as a ‘Monodramma di costumi antichi’- a piece for a solo performer in antiwue dress) with the music and libretto composed by Giorgio Battistelli. In 2019 there appeared Curiosa, Lou Jeunet’s French film depicting the complex relationship between Henri Regnier, his wife Marie (nee Heredia) and Louys. Pierre and Marie conducted a protracted affair, both before and after her marriage to Louys’ friend Regnier.

What then, is the legacy of Pierre Louys? I would argue that it is manifold: Louys was- first and foremost (of course)- a talented writer, immensely skilled in versification, capable of compelling plots. His works formed the vehicle for more though: examinations of religion, morality and social relationships; ideas for the ideal form of the state and government. This wasn’t just theory, as we’ve seen, but had real, practical results. What’s more, and for the very reason that he was a notable author and poet, he inspired others artists- composers, playwrights, painters, illustrators, sculptors, film makers, photographers- to create their own works. This seems, to me, an impressive record, nearly a century after his death.

For more on the writing of Pierre Louys, see my bibliography of his work; for details of my own writings on his novels and poems, see my books page.