The poems and novels of Pierre Louys were always destined for publication in illustrated editions. The writer himself was a decent draughtsman and photographer, whose images of his lovers were clear complements to his verse. His authorial imagination was such that he conceived of his works as a succession of ‘scenes,’ whether those might be imagined as theatrical or pictorial. What’s more, from the outset, his published work was quickly reissued in illustrated volumes, as commercial publishers appreciated how ideally suited they were to such editions. The text offered episodes readily translatable to visual form whilst the erotic content had an instant appeal to buyers. As I’ve argued before, the illustrated editions of Pierre Louys’ various books constitute a major literary corpus that also has considerable art historical significance: sixteen different works were illustrated by in excess of one hundred and thirty different artists and were issued in a total of over one hundred different editions.

The foregoing figures are impressive, but in concentrating upon them the danger is that the wider context within which such remarkable productivity was possible is taken for granted. We risk making the mistake of simply accepting that the publishers, artists- and market- were all available, but in reality a major contributing factor to the sheer wealth of artistic creativity that enhanced the writer’s own literary originality lies in the special circumstances of the book trade and visual arts in Paris during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Publishing & censorship

Perhaps the foremost facilitating factor was the relatively relaxed attitude of the French authorities towards the erotic book trade. Explicit depictions of sexual activity tended to be risky- which is not to say that out and out porn was not produced (but it was frequently undertaken covertly), nor that depictions of sexual contact were avoided where they could be defended as being ‘artistically justified.’ Editions of several of the more explicit works by literary authors included explicit plates- such as Guillaume Apollinaire’s Onze Milles Vierges (1942) and an edition of Paul Verlaine’s pansexual Oeuvres libres published by Jean Fort in Paris but which claimed to originate “À Eleuthéropolis” (near Hebron in Palestine). This attribution was a blatant attempt to pretend that the book was nothing to do with a French publishing house- one which was plainly still hedging its bets.

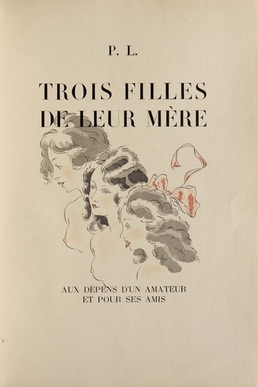

Many of the most explicitly erotic works of Pierre Louys were published following his death in 1925, and were accompanied by suitably graphic illustrations. Once again, these texts commonly alleged that they had been published outside France. For example, the 1929 edition of Bilitis apparently came from the Greek island Mytilene, where the heroine of the story lived, and the 1940 edition of Douze douzains de dialogues originated “A Cythère” (at Cythera, one of Aphrodite’s islands). The 1935 edition of the verse collection, Poésies Érotiques, claimed it came from Chihuahua, Mexico; the 1934 edition of Trois filles de leur mère alleged that it came from Martinique. These foreign publishers all sound highly improbable, and it’s surely likely that the authorities had a pretty good idea that they had really been produced in Paris. These stratagems aside, the book trade thrived for the first five decades of the twentieth century and, in its turn, encouraged a rich aesthetic community to complement it.

Paris- city of culture

Paris had been a centre of artistic excellence for several hundred years. In the recent past, of course, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Surrealism and other movements had been particularly linked with the city and, as a result, it had become a magnet for artists nationally and internationally, drawn by its schools, ateliers, salons, dealers and galleries.

A good example of the city’s draw for, and impact upon, painters may be the Bulgarian-born Jules Pascin (1885-1930). After studying and working in Vienna and Munich, he moved to Paris in 1905 and became immediately involved with the bohemian artistic and literary circles of Montparnasse, where he got to know painters and writers including Hemingway and Picasso. He enrolled at the academy run by Matisse and, on that painter’s recommendation, regularly visited the Louvre, where he copied the works of such eighteenth-century masters Greuze, Boucher, Van Loo, Watteau and Fragonard. Pascin’s own taste for erotica and nudes was doubtless reinforced by seeing these earlier painters’ canvases. Whilst Pascin was never commissioned to work on a book by Louys, he did produce a painting based upon Roi Pausole and, in the tight knit artistic community of the French capital, he knew illustrators such as Andre Dignimont and Marcel Vertès.

The artistic community of Paris was close-knit and somewhat incestuous and doubtless artists passed around news of possible commissions to illustrate books when they were drinking in Montmartre bars. The artistic capital of the world fostered talent in other ways, too: Auguste Brouet, who illustrated Louys’ Roi Gonzalve in 1933, earned money early in his career by producing cheap reproductions of paintings by other, much better-known artists- another good way of honing one’s skills and the instinct for what makes a good composition.

Magazines

A great deal of explicit material (written and visual) was tolerated by the French authorities and plainly contributed to a European perception that Paris was a uniquely ‘naughty’ place. Such an impression of ‘sauciness’ was doubtless further bolstered by the large number of magazines, such as La Vie Parisienne and Fantasio, in which suggestive images of glamorous nudes habitually appeared. The artist Chéri Hérouard is very typical of this genre. A good example of his output is a cartoon of a mermaid that appeared in Fantasio in 1921. The mermaid is seated, naked of course, on the sea floor, looking up at the bottom half of a woman in a bathing costume swimming above her. The image surely has a double entendre: the sea creature marvels amusingly at the strange behaviour of terrestrial beings, but at the same time we may enjoy the frisson of wondering if she is tempted by the shapely thighs and lower torso passing within touching distance. Topless or thinly veiled mermaids and nymphs regularly graced Herouard’s work, as did young beauties bound, or being either spanked or whipped, which were also popular with the artist. See too my post on the work of Georges Redon.

The importance of these magazines is not just what they tell us about the generally permissive mood in Paris, but also what they demonstrate about the artistic community working there. There was very evidently a pool of graphic artists with considerable skills in draughtsmanship and effective composition, upon whom the journal publishers could draw for cartoons, satirical sketches and other illustrations. Artists who worked on comic books or drew cartoons for newspapers and magazines included Jacques Touchet and Georges Beuville (both of whom worked on editions of Louys’ Roi Pausole), whilst Maurice Julhès, Pierre Lissac, André-Edouard Marty, Lucien Metivet and Maurice Leroy all illustrated Bilitis as well as drawing humorous sketches.

Graphic Novels

More recently, as I have described before, graphic novelists have been commissioned to work on Louys’ texts: Georges Pichard used his stark monochrome style to bring out the bleak depravity of Trois Filles in 1980 and Kris de Roover leavened the incest of Roi Gonzalve by means of bright colour blocks in 1990. Both these artists worked in established traditions, with Pichard drawing upon the inspiration of Robert Crumb and de Roover designing in the Belgian graphic style of ligne claire, initiated by Tintin’s creator Hergé. A close friend of Hergé was another Belgian, Marcel Stobbaerts, whose primary coloured and cartoonish illustrations of Pibrac from 1933- in which sexual explicitness and ribald humour combine- would seem to be another source of inspiration for de Roover.

Even more recently, the British artist, Robin Ray (born 1924), who uses the pseudonym Erich von Götha, illustrated an edition of a play by Louys, La Sentiment de la famille. Ray is known for the erotic and sadomasochist content of his illustrations and comic books. His most famous work is the series The Troubles of Janice, set in the time of the Marquis de Sade. The emergence of adult ‘comix’ (with an emphasis on the ‘x’) has provided a new medium for the presentation of Louys’ works to a modern audience.

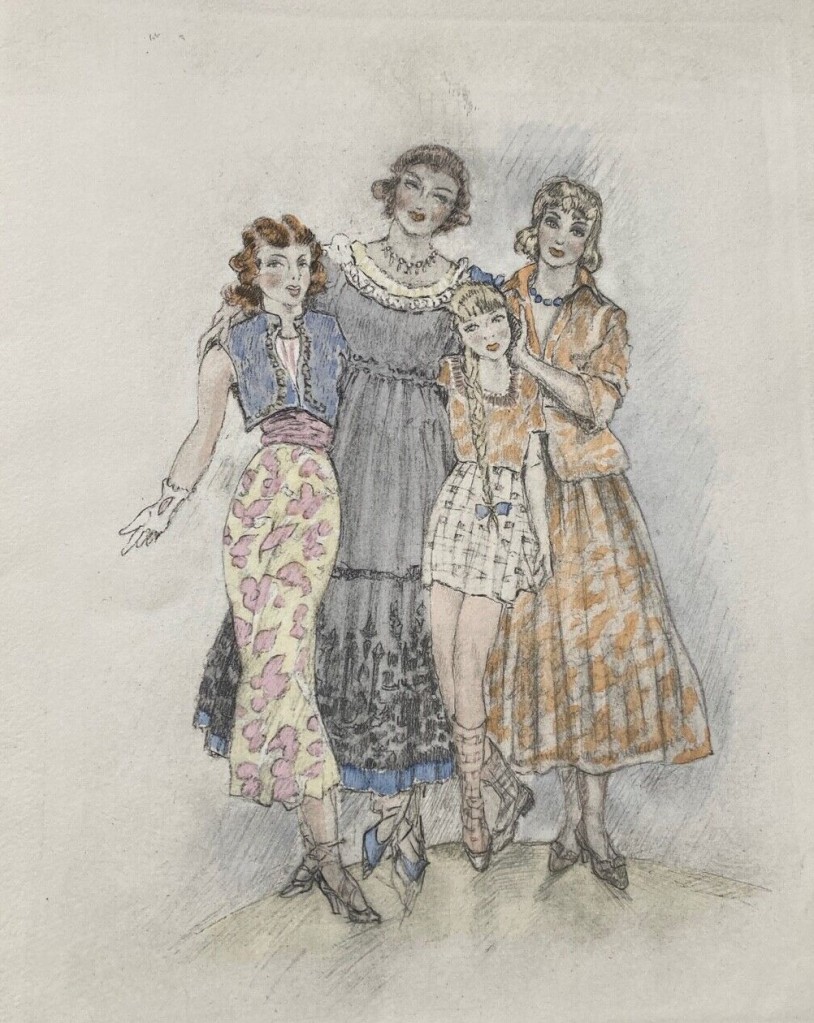

The design of pin-up images is also something for which quite a few of the illustrators of Louys have been known. Early in his career, Georges Pichard honed his characteristic female character in such images (see above). The same is true of René Ranson (Trois Filles, 1936) and Raymond Brenot (an edition of Sanguines, 1961)- their partially nude figures were often incorporated into adverts and calendars for products such as motor oil (see commercial art later).

Children’s Books

A form of illustration related to comics and cartoons is that of children’s books, and the list of artists who provided plates for these- but who also worked on texts by Louys- includes Pierre Lissac, both Pierre and Maurice Leroy, Rojan, Maurice Julhès, Pierre Rousseau and Renée Ringel. Although there was an obvious gulf between the books’ contents, those artists working in the junior, as well as adult, markets had very valuable skills and were plainly in demand. Publishers appreciated that they could instantly capture the essence of a scene in a concise and attractive image- one that could not just complement but enhance and propel forward the narrative beside which it was printed.

Commercial Art

Another branch of commercial art that also provided employment for talented draughtsmen was found in the continual demand for posters and advertisements and many significant painters and illustrators also made (or supplemented) a living by such work. Amongst the artists who undertook commercial design work (as well as illustrating works by Louys) were Nathan Iasevich Altman and Jean Berque (Bilitis, 1932 and 1935 respectively), Pierre Bonnard (Crepuscule des nymphes, 1946), André Dignimont (Bilitis, 1947) and Maurice Leroy (Bilitis, 1948) in addition to which there were those artists who were illustrators of multiple works by Louys- such as André Collot and André-Edouard Marty. Amongst the many multitalented and adaptable artists whose commissions included illustrations for magazines as well as Louys’ books were Georges Barbier, Luc Lafnet, Rojan and Louis Icart.

Finally, theatrical design was another source of income for jobbing artists, and illustrators who earned additional money creating sets and costumes included René Ranson and Georges Barbier. Barbier also designed jewellery whilst the painter and illustrator Pierre Bonnard made furniture.

French Literature

Furthermore, Pierre Louys did not write in an artistic vacuum, neither literary or pictorial. His period saw not just an outpouring of cheap porn paperbacks alongside frank, sexually themed poetry and novels from authors like Collette, Rimbaud, Verlaine and Apollinaire; there were also regular reissues of earlier texts- for instance, new editions of eighteenth-century work by Casanova, Laclos (Les Liaisons dangereux) and, of course, the rediscovered and newly popularised Marquis de Sade. Very many of these volumes were illustrated- very frequently by the same artists who worked on titles by Louys.

Independent of literary erotica, and the illustrations that accompanied those works, it’s important to notice that artists were also producing their own freestanding portfolios of adult imagery. The Austrian Franz von Bayros (1866-1924) is particularly significant in this genre, but French/ Belgian artists André Collot and Martin van Maele, and Russian émigré Rojan, deserve mention because all three also provided plates for books by Louys. Van Maele and von Bayros shared a distinctly gothic or grotesque taste; all of them explored the complex but controversial interplay between sex, sexuality, perversion and various degrees of force and violence (see too Jules Pascin’s pen drawings and his 1933 portfolio Erotikon or the Sade-inspired portfolios of Fameni Leporini).

What these conjunctions emphasise is the fact that the illustrators just mentioned didn’t only respond to the content of the texts by Louys upon which they were commissioned to work. Their independent collections demonstrate that those books were merely reflective of wider interests and obsessions in European society at that time. However, the purely visual representation of these themes in the portfolios brings these themes more starkly and unavoidably to our attention. Decadence and Bohemianism were not just meaningless labels- in the books and etchings we are often witnessing the first stirrings of sexual liberation and a permissive society. Louys- along with many others- was a harbinger of these shifts in social attitudes, although he may have felt that his promotion of Greek social values and an openness to greater diversity and freedom of personal expression fell on deaf ears in his time.

Summary

In conclusion, the illustrated editions of the many novels and poetry collections of Pierre Louys stand as a remarkable body of collaborative creativity, a literary and artistic legacy deserving of much wider critical study and popular appreciation. These joint productions underline the degree to which individual artists depend upon the work of others. Pierre Louys’ achievements arose upon the foundations of previous writers, painters and illustrators, who had created an aesthetic and intellectual environment within which he could develop his own particular vision. As for the craftsmen and women whose images enhanced his words, this brief review repeatedly demonstrates how multi-talented they were, able to produce memorable designs in a wide range of media.

A longer, fully annotated version of this essay can be downloaded from my Academia page.