Marcel Vertès (1895-1961) was a costume designer and illustrator of Hungarian-Jewish origins. He was born in Budapest and his first commercially successful works of art were sketches of corpses, criminals and prostitutes he made for a sensationalist magazine in Budapest (he subsequently published a portfolio of this work as Prostitution in 1925). Vertès later provided illustrations for many of the clandestinely printed publications opposed the continuation of the Hapsburg monarchy and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the aftermath of the First World War.

After the Great War, Vertès moved first to Vienna and thence, in 1925, to Paris, where he became a student of fine art at the prestigious Academie Julian. He quickly established himself on the Paris art scene, concentrating on illustration, painting and printmaking, especially lithography. He became a close friend and disciple of fellow émigré Jules Pascin, with whom he shared many tastes and interests.

Amongst the work Vertès undertook were forgeries of Toulouse-Lautrec’s works, which helped him earn his art tuition fees. His illustration commissions included working on various erotic books, which included several works by Pierre Louys. Amongst the titles Vertès illustrated were La Semaine Secrete de Venus, 1926, which was written by Pierre Mac Orlan, a leading author of erotic and spanking fiction during the interwar period in Paris (and another friend of Pascin’s); also Collette’s Cheri in 1929 and the collection of Guillaume Apollinaire’s poems, Ombre de mon Amour, in 1956. These may all have led to his commissions to work on several books by Louys, but it may also have helped that Vertès (like Toulouse Lautrec and Jules Pascin before him) seemed to have a good knowledge of the world of Parisian brothels, as demonstrated by his album of colour lithographs, Dancings (Dancing Halls) which he produced soon after his arrival in Paris in 1925. This showed gay as well as straight bars and clubs. It was followed up, in 1932, by a portfolio titled Dames seules (Women Alone), which comprised fifteen lithographs by Vertès illustrating aspects of lesbian life in the capital: couples together in their homes, women’s bars, women cruising for sex in the Bois de Boulogne and, in one case, a woman catching her girlfriend with some else.

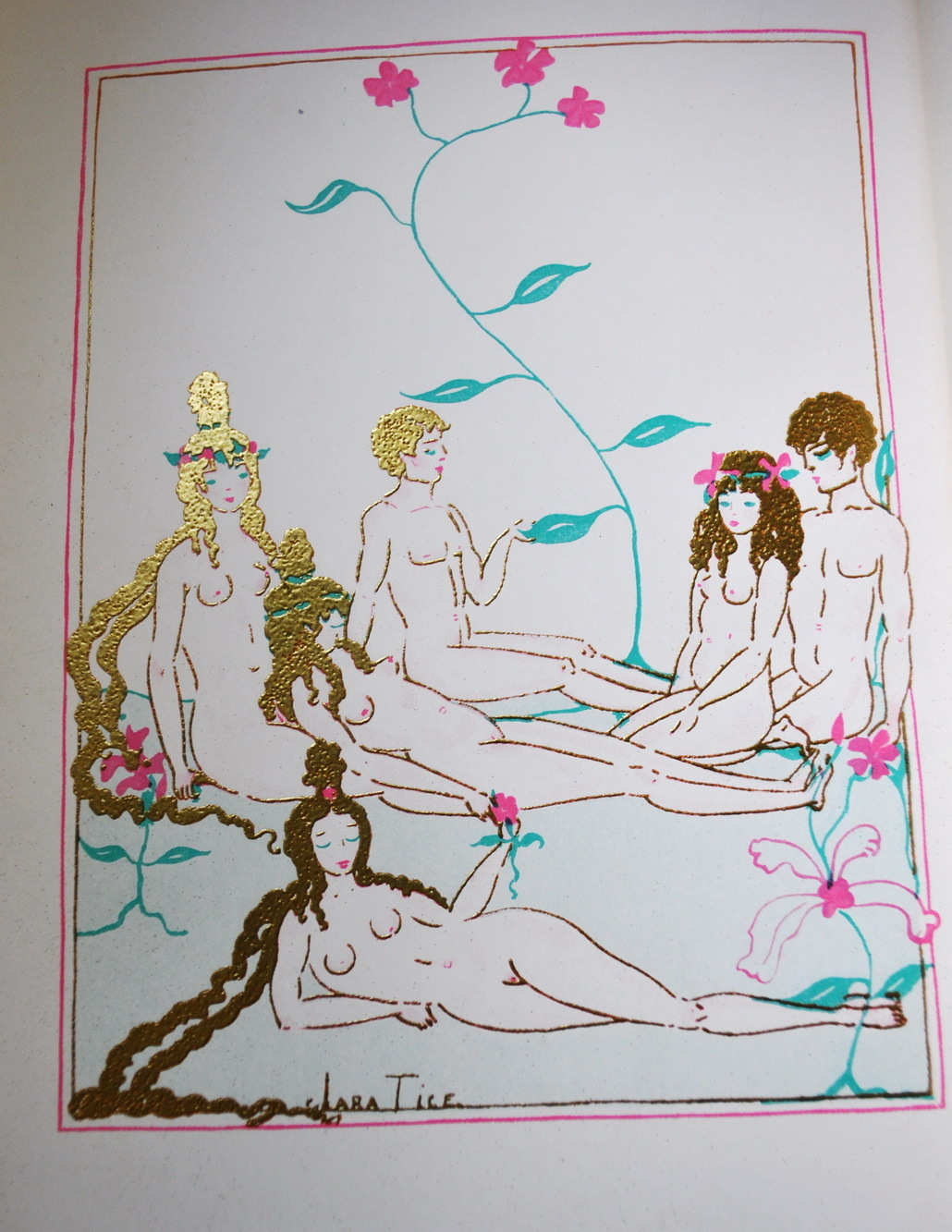

The artist first tackled Pierre Louys’ novel Trois Filles de leur mere in 1927. His seventeen dry-point prints were graphically faithful to the text; Vertès depicted all the perversities of the family at the heart of the novella. Next, Vertès illustrated Pybrac in 1928, unflinchingly recording the highly varied sex and sexuality that features in the hundreds of short poems that make up the collection. The artist also contributed plates to an edition of Les Aventures du Roi Pausole in 1932, which faithfully detailed the incidents of the story in thirty-eight pen and ink drawings. Six years later, he tackled Pierre Louys’ Poésies érotiques. Much like Rojan’s version of the previous year, Vertès provided thirty-two pencil and watercolour plates that fully portrayed all the lesbian and other incidents narrated in the verses.

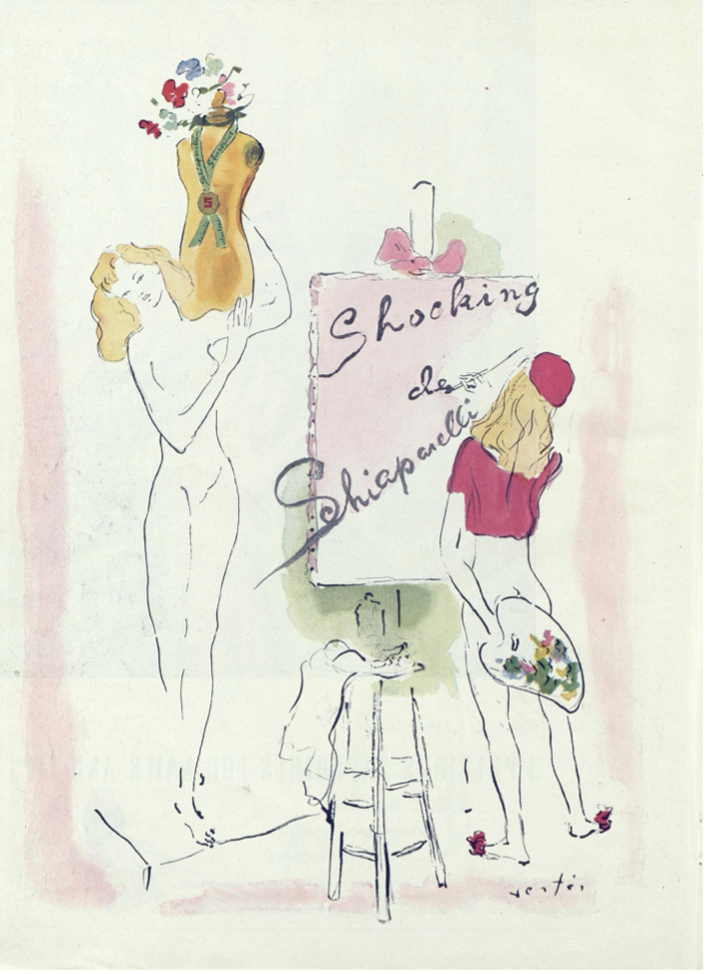

In 1935 Vertès made his first trip to New York in search of business contacts. Two years later he staged his first one-man exhibition in New York. That same year, in Paris, he provided the fashion designer, Elsa Schiaparelli, with advertisements for her new perfume called Shocking, work that was considered rather suggestive and a little shocking by some in the industry, with their hints of dryads and discrete nakedness. Schiaparelli herself obviously liked the artist’s work, for the campaign ran for seven years.

At the start of Second World War, Vertès returned to New York with his wife, escaping the Nazi invasion of France by just two days. Ten years later, he returned to live in Paris but still maintained his lucrative professional contacts in the USA. These led his work on the 1952 film Moulin Rouge about the life and times of artist Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec, for which Vertès won two Academy Awards; in addition, he painted the murals in the Café Carlyle in the Carlyle Hotel and in the Peacock Alley at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York. Furthermore, he designed the sets for Ringling Brothers’ Barnum and Bailey Circus in 1956, contributed illustrations to Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and was a jury member at the 1961 Cannes Film Festival. In France, his work was recognised when he was made an officer of the Legion d’Honneur in 1955, after designing sets for ballets at the Paris Opera. Vertès also published a number of books himself, including The Stronger Sex, Art & Fashion in collaboration with Bryan Holme, It’s All Mental, a satire on psychoanalysis, and Amandes Vert, an illustrated biography.

As his enormously eclectic output will indicate, Vertès was able to work in a variety of styles and media, turning his hand to almost any commission he received. In this, he resembled many of the illustrators I have described in my postings: whilst they may have regard themselves as painters or engravers, earning an income demanded that they were constantly flexible over subject matter and materials.

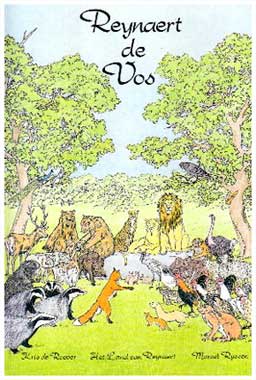

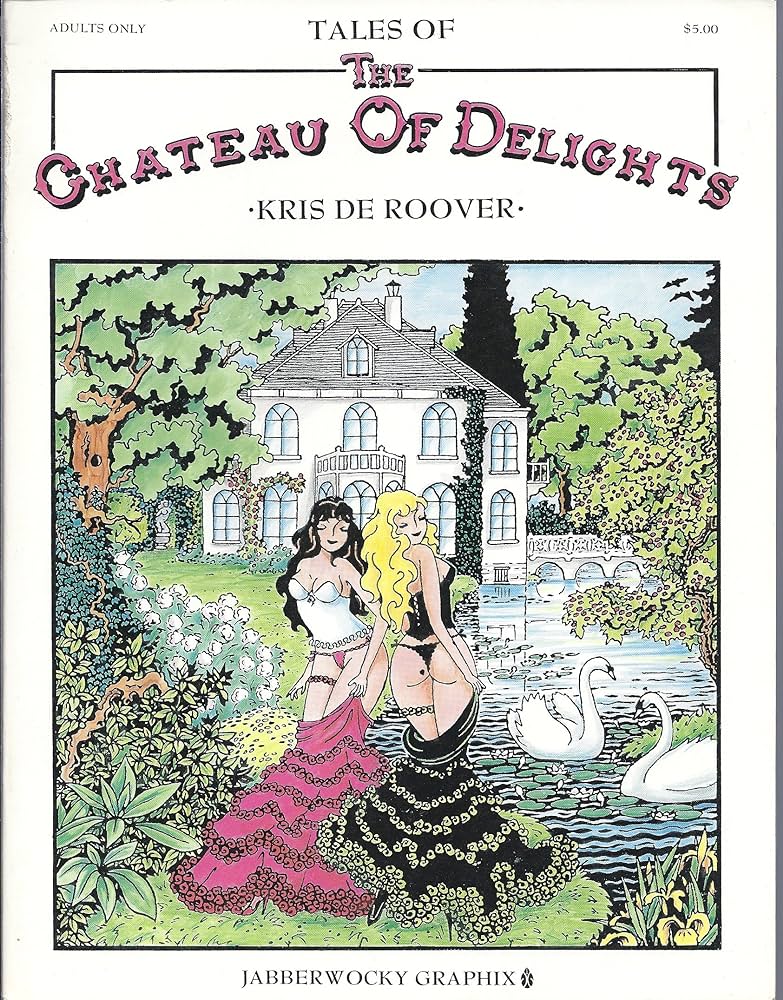

Kris de Roover (born 1946) was an artist from Antwerp, Belgium. He studied architecture before becoming an illustrator and, during his career, worked on illustrating a wide range of subjects, including erotica, with his designs being published across Europe and in the USA. De Roover employs revived the ligne claire style of comic art, which was pioneered in Belgium by Herge and other artists at Tintin magazine.

De Roover illustrated a comic strip version of Marcel Russen’s retelling of the medieval tale of Rynaert de Vos (Reynard the Fox, 1999), Die verhalen uit het kasteel der lusten- het verboden boek (1984- which was translated later as ‘The Chateau of Delights,’ 1990) and Pierre Louys’ L’Histoire du Roi Gonzalve et des douze princesses (1990). He also created the children’s comic De Tocht der Petieterkees (The Tour of the Petieterkees, 1989).

My interest here is de Roover’s work on Roi Gonzalve. His previous work on Het kasteel der lusten, had indicated a talent for erotica, but the uncompleted novel by Louys represented a challenge to his representational skills. The origins of the story itself are unclear; the king seems to be an invention of Louys, taking his name from the eleventh century king Gonsalvo of the counties of Sobrabe and Ribagorza in the Pyrenees (and, as such, being a neighbouring realm to the imaginary kingdom of Trypheme in Louys’ Les Aventures du Roi Pausole). The twelve princesses of the full title, and their unnatural relationship with their father, may be an echo of the twelve children that the god Uranus had with his sister Gaia in the Greek myth of the Titans. Moreover, one of these offspring, Cronus, had six children with his sister Rhea and two of these, Zeus and Hera, became husband and wife, although Zeus previously was married to his aunt, Themis, sister of Cronus and Rhea. Rather like cartoonist Georges Pichard in his earlier work illustrating Louys’ Trois filles de leur mere, it seems that the Spanish publisher of Roi Gonzalve considered that a graphic novel style would be the best way of tackling the adult content of the story, thereby creating some distance and unreality. De Roover accordingly seems to have depicted the king as a louche, Lothario-like figure in a dinner jacket with a large seventies moustache, a slightly dodgy looking monarch whose character was well suited to the plot of the unfinished text, such as it is.

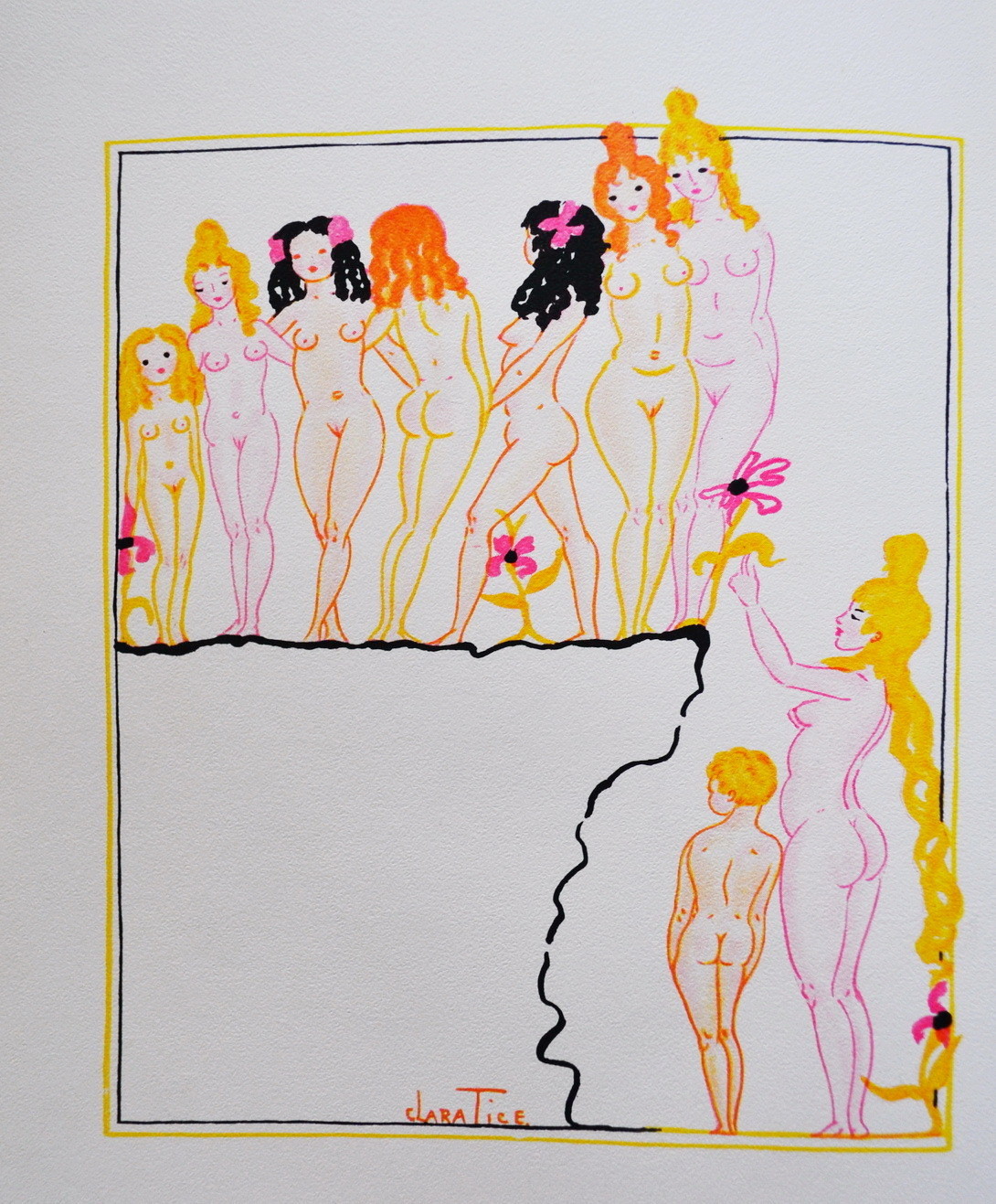

De Roover’s choice of style for the book involved emphasising elements in his previous work: his plates feature strong outlines and very brightly coloured designs, using blocks of colour for each figure or item and depicted in a very simple manner (a style that might be very suitable for a children’s book- although primary tones are distinctly stronger than those he used for Reynaert de Vos in 1999). De Roover surrounded these with a pen and ink border design of female nudes which closely resemble his delicate work in the Kasteel der lusten. These elements further help to reduce the challenging nature of the content and to lighten the mood, by making the novella seem more like an action comic. It’s notable too that de Roover, like Paul-Emile Becat before him, chose to depart from the text of the book and overall raised the ages of the princesses he drew, lessening some of the potentially controversial impact of Louys’ narrative, although his plates are still explicit and are clearly tied to the text with quotations of the passages depicted.

We may well wish to reflect upon the fact that the two most recent illustrators to work upon the posthumously published works of Pierre Louys felt that such a style was more suitable or acceptable. For more discussion of these issues, see my Pierre Louys bibliography. For more discussion of work of Vertes and de Roover and of the illustrated editions of the works of Pierre Louys in their wider context, see my book In the Garden of Eros, available as a paperback and Kindle e-book from Amazon.