The Adventures of King Pausole (Les Aventures du Roi Pausole) was the fourth major novel written by Pierre Louys. It was published in 1900, two years after his modern romance, La Femme et le pantin (Woman and Puppet) and it returned to his habit of constructing fantasy lands, or utopias, although in this case he imagined a Pyrenean kingdom in the present day rather than a simulacrum of the Greek past.

King Pausole is the monarch of a modern day pagan kingdom. He rules benevolently and encourages a relaxed and carefree lifestyle amongst the population. The king himself has a wife for every day of the year and young people in his realm go around naked except for shoes and headwear until they marry; polygamy and polyandry are both permissible. The adventures of the novel’s title concern the king’s rather short journey from his palace to his capital in search of his daughter, Aline, who has fallen in love with a dancer called Mirabelle and has eloped with her. The two are found and matters are resolved, with Aline pairing up with a courtier called Giglio and Mirabelle meeting the young woman who will become the love of her life, Galatee.

As with his other major books, Pausole ran through over a dozen and a half illustrated editions. Just like my review of the illustrators of Bilitis, I have divided my discussion quite arbitrarily, looking at books issued before and after 1930. The date of Louys’ death, 1925, might have been more logical in terms of chronology and the book trade response, but one post would have been much bigger than the other; likewise had I split the material between and after the Second World War.

The first illustrated edition of Pausole was by Carlegle in 1901; this was reprinted in 1908 and then again in 1924, as we shall see. Charles Emile Egli (1877-1937) was born in Aigle in Switzerland and studied engraving in Geneva before moving to Paris in 1900 to attend the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He took the professional name Carlegle, at first working as a humorous illustrator; he contributed to many comic and satirical newspapers and journals and his work often featured nudity and sex. However, in 1913, having provided wood blocks for an edition of Daphnis et Chloe, Carlegle switched solely to the illustration of literature, to which he felt he was better suited. As well as Louys, he illustrated Virgil, Paul Valéry, Blaise Pascal, Paul Verlaine, Sappho, La Fontaine, Diderot and Anatole France.

The artist Pierre Vidal illustrated a further edition in 1906 (see head of page). Marie Louis Pierre Vidal (1849-1913 or 1929) was known for his images of French life during the Belle Epoque. Like another Louys illustrator, Morin-Jean, Vidal originally trained as a lawyer, but then took engraving and drawing lessons. His illustrative work included Flaubert’s Salammbo, Merimee’s Carmen, Balzac, Alphonse Daudet and Guy de Maupassant as well as Louys. For Roi Pausole, he designed a remarkable 82 colour plates, which were decorated in a style clearly of the first decade of the twentieth century. Lucien Metivet, whose illustrations of Louys have been mentioned before, also worked on a version of Pausole in the very same year, but the plates have little notable about them.

There then seems to have been a lull in demand for the text, as it was only two decades later, after the end of the Great War, that interest revived. In 1923 an edition with woodcuts by Fernand Simeon (1884-1928) appeared. Simeon was a painter and watercolourist, but he specialised in the wood-block printing of book illustrations and was renowned for his skill in the technique. The Simeon edition was quickly followed in 1924 by a new edition again illustrated by Carlegle, who provided a generous 87 colour illustrations, all reflective of the then current fashions. The bright, primary colours of the 1924 edition contrast pleasingly with the austere black and white drawings from 1906, emphasising the cartoonish elements of the draughtsmanship.

With the death of Pierre Louys in 1925, publishers saw an opportunity and further editions followed over the succeeding five years. The first included designs by Clara Tice, whose work we have encountered before. She created a full colour frontispiece and nine other two colour full-page plates for an English language translation in 1926. As we saw in her illustrations for The Twilight of the Nymphs, there is the rich use of gold coupled with bright pinks and greens and a childlike innocence to the drawing.

Two other English translations were published in the United States during the 1920s. Firstly, the ‘Society of Sophisticates’ issued a version in 1920 illustrated by Lotan Welshans (1905-85). Then, in 1929, a new edition with plates provided by satirical draughtsman Beresford Egan (1905-84) appeared. Both books seem to have been reprinted a number of times. As you’ll see, Welshans’ designs are attractive, but they can’t compete with the colourful and highly stylised plates from Egan.

Two further French editions came out in 1930. The first was a lavish, limited-edition printing illustrated by the Italian artist Umberto Brunelleschi (1879-1949) with seventeen pouchoir (stencilled) colour illustrations. Brunelleschi moved to Paris in 1900, where he worked as a printer, caricaturist, book illustrator, set and costume designer. These are gorgeous, full-page plates, in a striking art deco style, which bring out the full erotic nature of the text, although the artist makes the king look rather younger and more vigorous than Louys’ text would suggest.

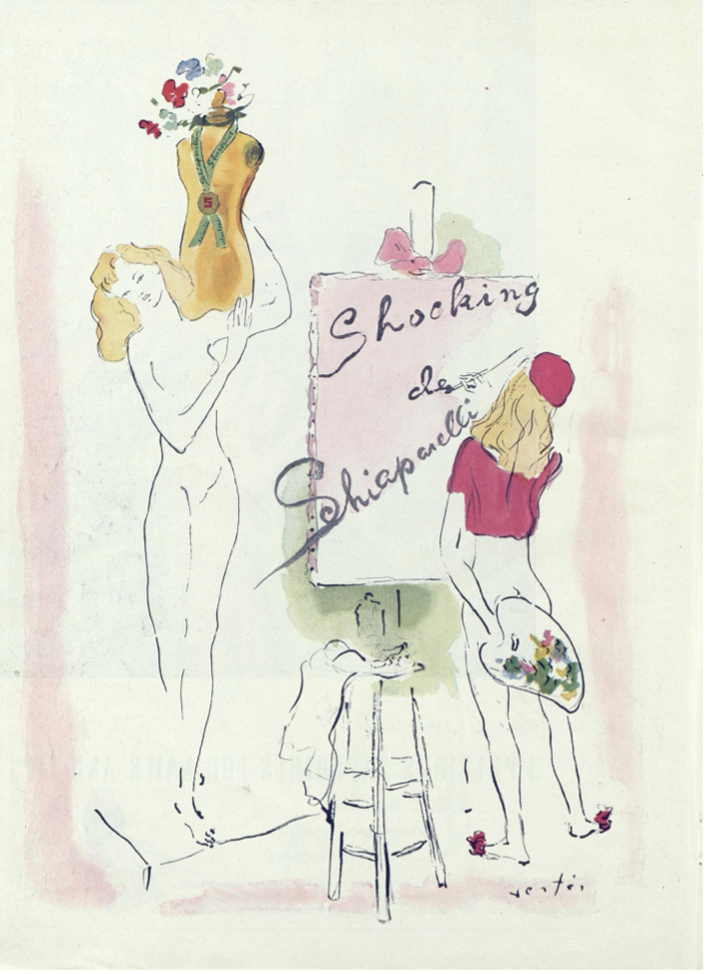

The second edition of 1930 was rather less ambitious and extravagant. It was illustrated in a more conventional style by Nicolas Sternberg (1901-1960). Like another illustrator of Louys, Marcel Vertes, Sternberg was born into a Jewish family in Hungary. Little is known about his early years, but he spent some time in Munich, where he may have been influenced by Expressionism, before arriving in Paris. There he established a career as a prolific artist and illustrator of books and magazines such as Elle. Sternberg survived the Second World War by hiding under a false identity.

Sternberg is known for his nude studies, as well as for his portraits of women, dancers and theatre actors. He also provided illustrations for the erotic and fetish novels for which Paris was famed during the interwar years, something which may have recommended him for work on Louys’ novel. Sternberg’s faces are always expressive, something of which can be seen in his work on Pausole. The characters’ faces, with their pouting lips, have a charming innocence at odds with the nudity that pervades the text. His King Pausole is again rather more youthful and virile looking that Louys suggested; he has a harem of 365 wives and Sternberg’s rendering suggests that the king is fully up to the challenges that might present to him.

As stated, the review of editions of Roi Pausole will be continued in a further post. For more information on the writing of Pierre Louys, see my bibliography for the author and my own essays and books on his work.

For a complete discussion of the illustrated editions of the works of Pierre Louys in their wider context, see my book In the Garden of Eros, available as a paperback and Kindle e-book from Amazon.