I have written a good deal about the books of Pierre Louys and about the numerous illustrated editions of those works that have been published. I now want to consider how the work of the Marquis de Sade has been treated by the publishing trade. As many readers will appreciate, de Sade bears many striking resemblances to Louys- the Marquis was doubtless an inspiration to the latter and they both dealt with similar themes of transgressive sexuality in manners that were sometimes shocking and provocative. Sade was, though, much more of a philosopher than Louys, far more concerned with wider social and political questions. Very narrowly, the content of their books guaranteed stimulating material for artists to work with, so that publishers knew that illustrated editions would be likely to sell well within a certain market.

It’s interesting, therefore, to find that there are maybe twenty illustrated versions of de Sade’s key works (Justine, Juliette, Philosophy in the Bedroom and 120 Days of Sodom), not an insignificant number, perhaps, but dwarfed by the total of illustrated editions of Louys, which exceed one hundred and twenty on my latest reckoning. In the case of Sade’s most notorious title, 120 Days of Sodom, this may partially be explained by the fact that the manuscript of the text was only rediscovered and published by the poet Apollinaire and then by the surrealist Maurice Heine in the late 1920s. In point of fact, though, most of the editions of de Sade post-date the 1960s, suggesting that it was only in more recent decades that publishers felt that it would be acceptable to issue his works without the risk of public complaints and criminal proceedings.

I suspect that one of the first artists to respond to the works of Sade, since Bornet had illustrated the original editions of La Nouvelle Justine and Juliette in 1797, was the rather obscure French artist Fameni Leporini, probably in the 1930s. As others have observed, it seems very clear that the artist was working to a text (or texts), for otherwise some scenes make little sense to the viewer- their context is obviously lacking, as if they were meant to illustrate a narrative that is now absent. Personally, I regard his portfolios not as illustrations of specific titles, but rather as interpretations of the themes and scenes also addressed by de Sade (most obviously, I would suggest, Part Two of The One Hundred & Twenty Days of Sodom); this would seem to be confirmed by the inclusion of monks in a few prints as well as some images that show eighteenth century dress. Leporini was very capable of representing intense mutual passion between lovers, but he also reflected the violence and abuse of power that could be present in Sade’s works, meaning that he depicted not shared pleasure but dominance, distress and shame- an acknowledgment that male control and exploitation have often had the potential to distort interpersonal relationships.

In rather the same way, in the 1960s the German born surrealist Hans Bellmer produced a series of darkly erotic drawings and etchings inspired by the writer. These were interpretations of Juliette, Justine and 120 Days, but the works were unconnected to any edition of those books. The first was the drawing Life & Death (For de Sade) of 1946, A Sade from 1961 and culminating with the Petit traité de morale (A Little Moral Treatise) in 1968. Bellmer’s baroque images elaborate his figures’ anatomy in unreal ways that tend to dehumanise the subjects and distance the viewers. The results can be violent and disturbing, resembling dissection drawings, stressing that corporeality is close to decay and that lust verges on cruelty.

New illustrated editions of Sade began to be published during the 1930s. In 1931 Heine’s transcription of 120 Days, with 16 lithographs by Andre Collot, appeared. In the manner typical of Collot, the images were as explicit as this violent and pornographic text demanded. They recognised, nonetheless, that the pain and humiliation is shared in de Sade’s book, with seducers as likely to be whipped or degraded as their victims.

One of Sade’s most popular books has always been Justine- or the Misfortunes of Virtue. There was a German edition in 1900, with colour illustrations in eighteenth century style by an unknown author. These imitate Bornet’s plates from 1797, notably his tendency to pile up figures in improbable pyramids, and like their models the plates they are highly explicit. The book- probably consequentially- appeared in a very small print run. However, in 1931, the same year as Collot’s 120 Days, an English translation of Justine was published in New York, with 27 “spirited illustrations by Mahlon Blaine.” Blaine was a colourful character who liked to claim that he had been born on Easter Island. One dealer has described his work as walking “the razor’s edge between the grotesque and beautiful.” He was a self-taught illustrator notable for his darkly erotic images, which are to be found in books which also include Flaubert’s Salammbo (1927) and William Beckford’s Vathek (1928). As will be seen, there’s considerable vigour in his designs, as in the representation of Justine’s death seen below.

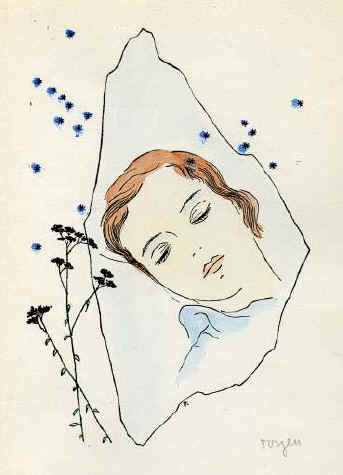

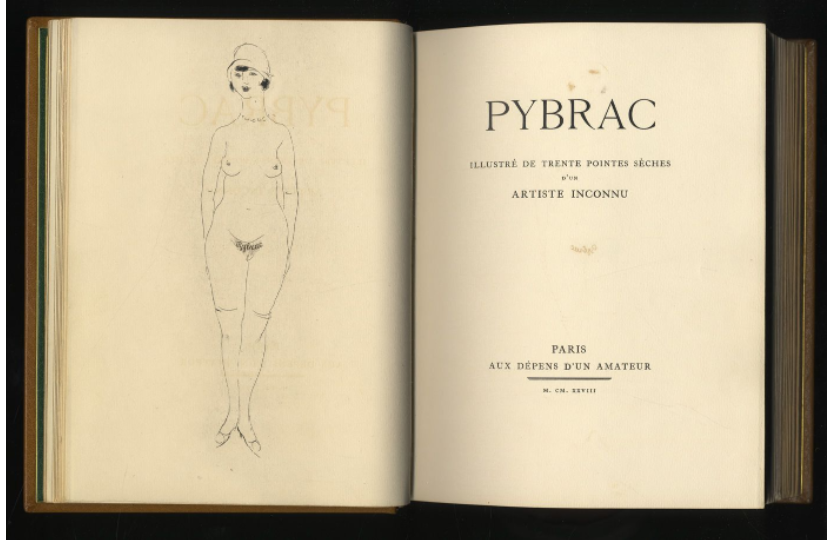

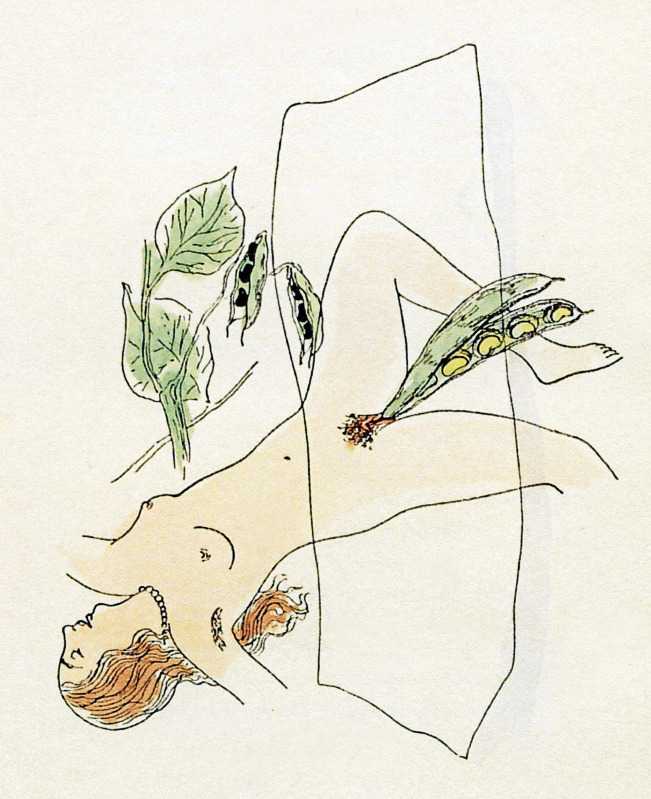

In 1932, the Czech surrealist Toyen (whom we have encountered before in discussing her illustrations for Pierre Louys’ Pybrac) provided plates for an edition of Justine. These match the rather abstract style of her work on Pybrac that same year. Toyen’s husband, Jindřich Štyrský (1899-1942) who was a surrealist painter, poet, editor, photographer and graphic artist, also designed a photographic cover for an edition of de Sade’s Philosophy in the Bedroom, as well as writing a study of the Marquis’ work.

A pause in publications followed until near the end of the war, when in 1944 a new edition of Juliette, illustrated by another Surrealist artist, the Argentinian Leonor Fini, appeared. The curator of a 2018 exhibition in New York on ‘Fini and the Theatre of Desire’ described how, for the artist, life was to be lived as an “investigation in the human psyche and, for her, gender and sexuality were the greatest ways to perform those kind of experiments, both on the canvas and in real time.” Fini illustrated about fifty books during her career, choosing authors and titles that coincided with her own interests. These included the Satyricon and works by Verlaine, Jean Genet and Charles Baudelaire. Fini’s twenty-two plates for Sade’s book responded in particular to the macabre elements in the text, emphasising skeletons and decay as much as erotica. This emphasis on mortality, I think, was her way of representing those aspects of de Sade’s work where carnal desire slips into cruelty and the reader/ viewer becomes uncomfortable and alienated.

Two years later another female illustrator, Lilian Gourari, provided twenty one plates for a new edition of Justine, ou Les Infortunes de la Vertu. I’ve been unable to find out much about Gourari (or Gourary), other than she illustrated only a few books- amongst them children’s books such as Les Neufs Lutins de la Montaigne (The Nine Gnomes of the Mountain). Her work on de Sade appears to be the most significant. She didn’t flinch from depicting the various misfortunes inflicted upon the hapless Justine.

A slowly accelerating flow of editions of de Sade had begun. In 1948 an edition of Eugenie de Franval (a story of incest and its punishment) appeared, with eight plates by Valentine Hugo (1887-1968). She was a writer and painter, best known for her work with Jean Cocteau and the Ballet Russes and her close association with the Surrealists (including an affair with Andre Breton). Her illustrations included editions of the Surrealist’s favourite, the Comte de Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror (1933) as well as the surrealist Paul Éluard’s Les Animaux et leurs hommes (1937) and Symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud’s Les Poètes de sept ans (1938).

Another version of Justine, this time illustrated by Schem, appeared in 1949. His twenty three coloured lithographs are typical of the sweet delicacy of his attractive illustrative work, featuring a good deal of nudity but nothing really shocking.

A hiatus followed during the 1950s, perhaps because the market seemed well supplied, but interest in de Sade revived in the ’60s with three new illustrated editions of his work. Curiously, all of these featured the work of young German artists. The eldest was Eberhard Schlotter (1921-2014) who worked as a painter in Spain and Germany. In 1967 he designed a set of sixteen etchings depicting episodes from Sade’s Philosophy in the Bedroom. The following year, the Polish-German Arwed Gorella (1937-2002) created 13 etchings for the second volume of Sade’s collected works (in German). The images- mostly portrait busts- remind me of those faces constructed from vegetables and fruit created in by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526-93)- except that Gorella (naturally) used naked bodies. Uwe Bremer worked on volume three of the same edition, using a radically different style but yet- like Gorella- capturing the same anatomical aspect of Sade’s work that so many other illustrators had identified.

In 1972 Johannes Vennekamp (b. 1935), the German artist and colleague of Uwe Bremer, produced a portfolio of thirteen etchings based on 120 Days. He too opted for a kind of diagrammatic graphic approach, in contrast to which was the refreshingly cartoonish work of caricaturist and illustrator Albert Dubout (1905-76), who illustrated Justine in 1976 with some exuberant and exaggerated images. Dubout (who was married to illustrator of Pierre Louys Suzanne Ballivet) worked on satirical magazines such as Le Rire and illustrated numerous books, including Rabelais Gargantua and Pantagruel; perhaps this background helped him to locate the humour in de Sade, finding his extreme situations so over the top as to be laughable rather than shocking. In 1979 Guido Crepax took the next logical step and rewrote Justine as an exquisitely illustrated graphic novel (see image earlier). A graphic novel version of Juliette, by Philippe Cavell, followed in 1983 (see cover image earlier). His other illustrated work includes an edition of Fanny Hill and various erotic novels such as Petites alliees by Clary F and Nini Tapioca by Beatrice Tessica.

Further illustrated editions have followed in the last few decades: these include (amongst others) Justine and Juliette by Martina Kugler (1945-2017) in 1991 and by Lisa Zirner in 2014. The former opted for simple pen drawings in an unusual ‘tribal’ or ‘primitive’ style, the latter for fifteen cheerful, bright, almost cartoonish illustrations which are notable for the joy and pleasure that she depicted amongst the participants. Interestingly, perhaps, in 1985 and 2006 respectively, both women had previously illustrated Histoire de l’œil by Georges Bataille, intellectual, philosopher and early associate of the Surrealists. The History is a 1928 novella that details the increasingly bizarre sexual perversions of a pair of teenage lovers. Bataille was heavily influenced by de Sade, making the separate publications quite closely linked.

Javier Gil (born 1961) created a series highly explicit pastels based on Philosophy in the Bedroom in 1996 whilst Alexander Pavlenko, who was born in Russian in 1963 but who now lives in Germany, has produced another portfolio of Sadean inspired works entitled A Sade- rather like several earlier German artists. Pavlenko’s approach was to produce rather exaggerated erotic images. Most recently, in 2014, the French illustrator Yves Milet-Desfougeres (1934-2022) created a series of quite crude-looking pen sketches to go with another edition of Philosophy; he too had also worked on Bataille’s Histoire de l’œil, in 2010.

Lastly, in 2000 a lavishly produced edition of Justine, with twenty designs by Cyriaque de Saint-Aignan, was published. These are impressive female nude studies, although not perhaps fully reflective of the book; the ‘glamour’ style of the pictures, most notably the frontispiece, which renders the virtuous and innocent Justine as a Carmen-like figure, seem at odds with the story.

What many of the illustrators of de Sade have confronted in the author’s texts is the risk that carnality can tip over into depersonalising cruelty, that a sense of the individual, consent and volition can be lost. This sets this body of work apart from many of the books I have previously discussed. Nevertheless, as I’ve proposed before, we see how the provision of illustrations with text can amplify the written word, reinforcing its impact as well as making the reader focus more closely upon what is being described or discussed. This can have an especially powerful effect with work such as de Sade’s.