Cornelis Kloos (1895-1976) was a Dutch painter and sculptor in bronze and terracotta with something of a controversial reputation. He was born into a wealthy mercantile family in Rotterdam and considered a number of career options as a young man. After finishing school he spent a period undertaking officer training in the army; this experience meant that, when the First World War began, he was immediately despatched to border guard duty, trying to catch smugglers entering occupied Belgium. He had planned to visit Tibet but this adventure was cancelled and his further education was put on hold until 1919.

Kloos then studied and successfully graduated in mine engineering (even though drawing had been his hobby from an early age, art was not initially something he considered as a career). Whilst studying engineering, he also attended philosophy lectures at the university, an interest that stayed with him throughout his life (for example, when his daughter reached fifteen, he told her she was old enough to start reading Plato). The young student then opting for the arts, undertaking his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in The Hague and passing the five year course in only eighteen months, which then qualified him to work as a drawing teacher. Having the guarantee of a steady income, he married, and, for a honeymoon, travelled around Europe. The young couple settled in Paris where he studied painting with the Cubist André Lhote at his academy in Montparnasse, Paris (although Lhote had very little direct or immediate impact upon his student’s style). Kloos then studied for three months at Hans Hoffmann’s Schule für Bildende Kunst (School of Fine Art) in Munich; Hoffmann became a major figure in Abstract Expressionism, but during the twenties was still a fairly conventional figurative and landscape painters. Kloos then returned home to teach drawing at the Hague Academy; during the 1930s his career as a painter took off and his teaching duties were relegated to evenings only.

Kloos took part in three consecutive Olympic Games in the art competitions- in 1928, 1932 and 1936. His entry Springende meisjes for the 1932 Olympics has been lost, but a reproduction survived. It is reported that the German Minister for Propaganda, Heinrich Goebbels, admired and wanted to buy the painting after the exhibition. However, he asked Kloos was to change the dark-hair of the gymnasts to blond, which- to his credit- he refused to do. The purchase did not proceed.

When the Second World War broke out, Kloos was briefly recalled to military service before Germany occupied the Netherlands. During the war, he apparently covered espionage activities noting down coastal troop positions by going on ‘painting trips’ to the dunes along the North Sea coast. After the war, Kloos was a lot poorer than he had been but he struggled along, living frugally and dedicated to his art. Sadly, by the 1950s, interest in his style of unfashionable pictorial and figurative work steeply declined whilst he had no sympathy at all for modern abstraction. Later in life, Kloos concentrated on writing about aesthetics and trying to establish a museum that would teach people to understand art, but these projects came to nothing and he felt considerable disappointment and frustration.

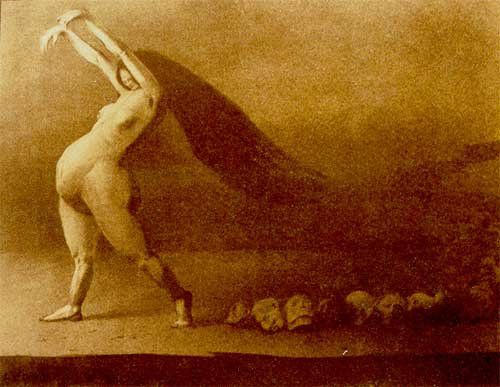

Although he produced some landscapes, Kloos concentrated upon nudes, painted in a realist style and almost exclusively using young women as his models. One Dutch auctioneer has said that the artist “obsessively painted and drew nude young girls in a way that came dangerously close to the boundaries of the pornographic – at least in our puritan times.” Another critic has spoken of Kloos’ “meisje fascinatie”- his ‘girl obsession’ and it is true that his liking for posterior pictures of the naked figures treads a very fine line between academic life study and ‘glamour’ shot. The artist’s daughter Carola has described how “He always sat in his studio, often with young girls as models, whom he sketched; he made his paintings based on the sketches. The models met him on the beach, for example, where he sat down to draw (which was always a crowd pleaser).” She also said of her father that, if he could be blamed for anything, it was his rather old-fashioned views on the nature of feminine beauty: “Woman is meant to allure,” he said. Carola does not try to defend his views and recognises that there in his work there “may have been sublimated sexuality, but can’t we say the same about the ancient sculptors or the Renaissance painters with their female nudes?” The parallels between Kloos’ work and that of Balthus are very clear; both artists had a lifelong obsession with a particular sort of model (although the young women painted by the Dutch artist are generally a little older than the adolescents depicted by the French painter). The image below- Meisje met roos (Girl with a Rose) has a pose very similar to that adopted by the models in numerous studies by Balthus, which makes me suspect that Kloos must have been familiar with the French artist’s work. I have shown an example of one of his paintings of Thérèse Blanchard; he created multiple pictures of girls in extremely similar postures.

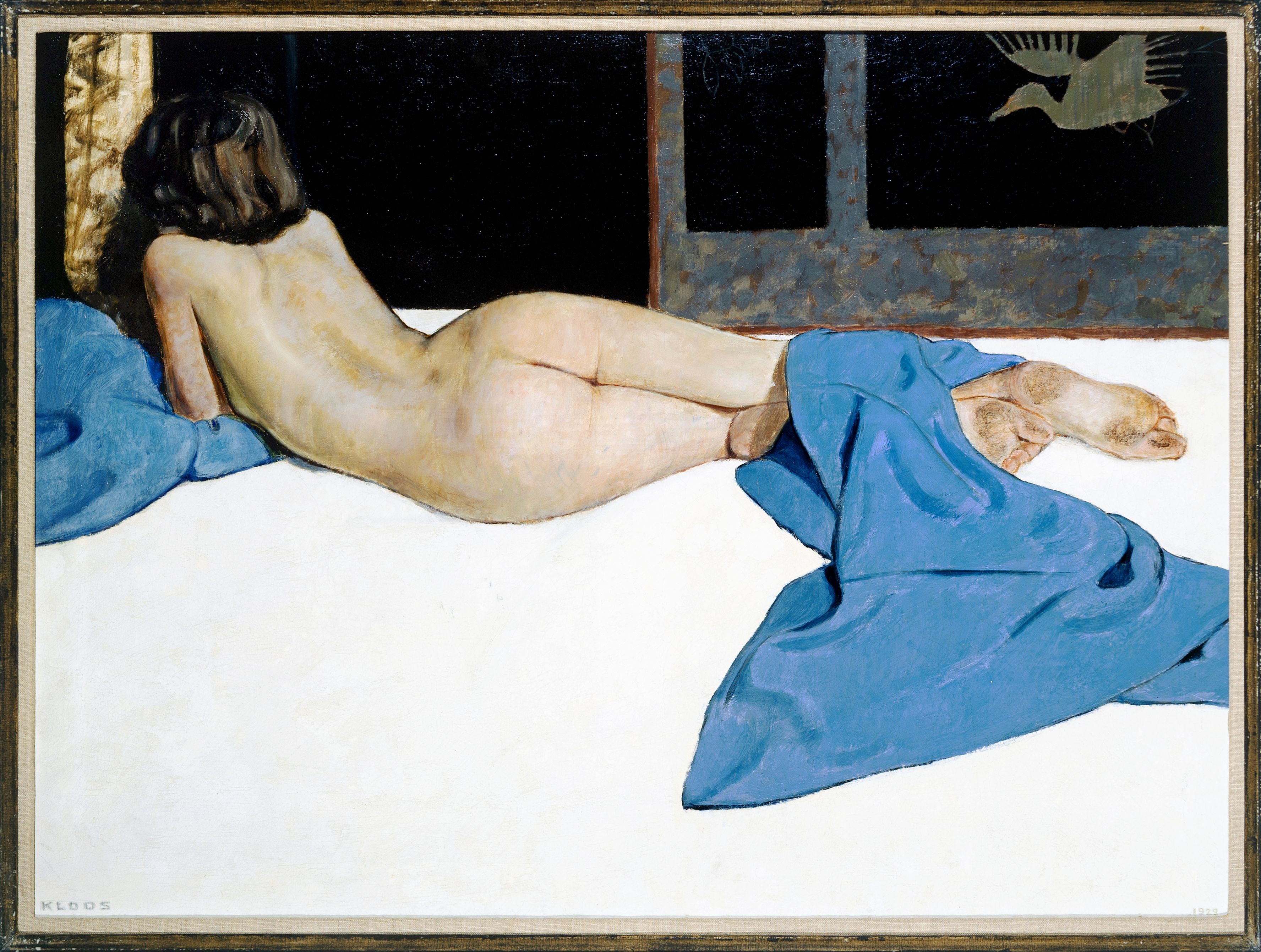

Many of the Kloos’ pictures are consciously sensual in their poses. As we’ve read, he often drew his models in the studio, an example being Naakt met blauwe doekt (c.1930), a sensual study that imitates Velazquez’ Rokeby Venus, yet at the same time is honest and unsentimental enough to show the dirty soles of the model’s feet.

Just as frequently, though, Kloos painted outside, in full sun: thus, Twee meisjes zittend op een strandlaken (c.1930, above) presents us with two glossy skinned girls sunbathing, Gondola of 1952 has its young subject stripping off on a pontoon before a swim and Springen (Jumping) from 1952, which is a kind of follow-up- two naked girls leaping into the water- and which must also echo his Olympics entry. It seems extremely likely such healthy, active nudity outdoors (somewhat akin to the output of Fidus) would have appealed strongly to Goebbels.

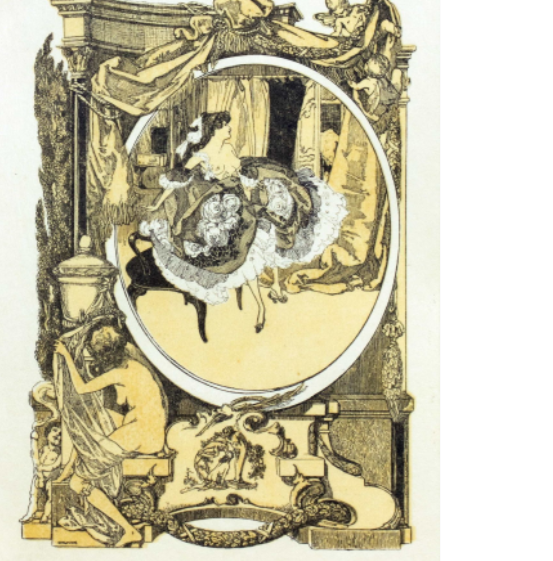

Despite the clear sensuality that imbues much of his work, Kloos often incorporated a sense of bizarre humour that has close parallels with the work of Austrian illustrator Franz von Bayros. In multiple paintings created post-war he incongruously juxtaposed young nudes outdoors with wildlife, such as Liggend naakt met hert, Alligators (1951), Ape Ring and Polar Bears (both 1952), as well as with sea-lions, a flock of sheep, a wolf and lions. The models’ responses to their circumstances vary- from surprise, through embarrassment at being seen naked, to fearless confrontation with the wild beasts. They seldom look threatened or truly vulnerable.

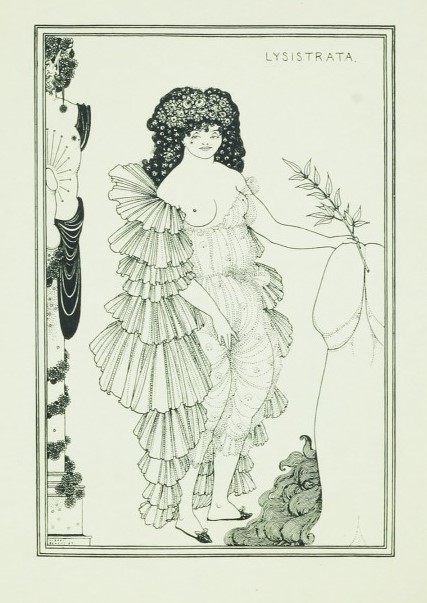

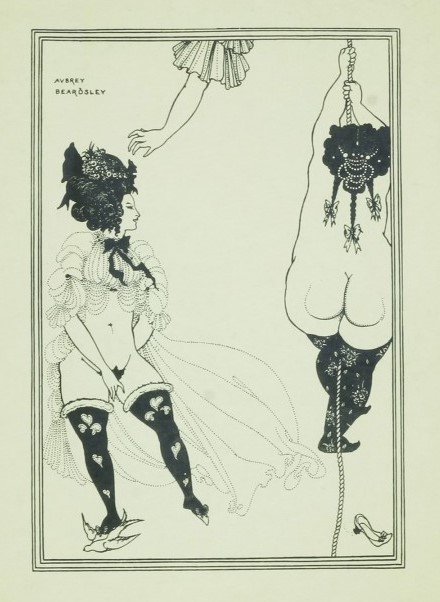

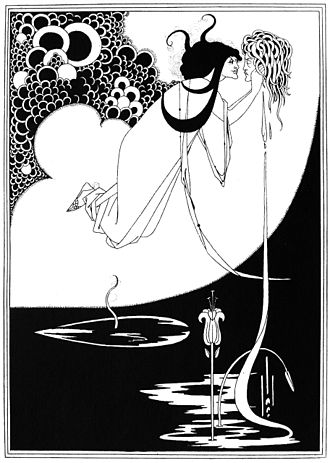

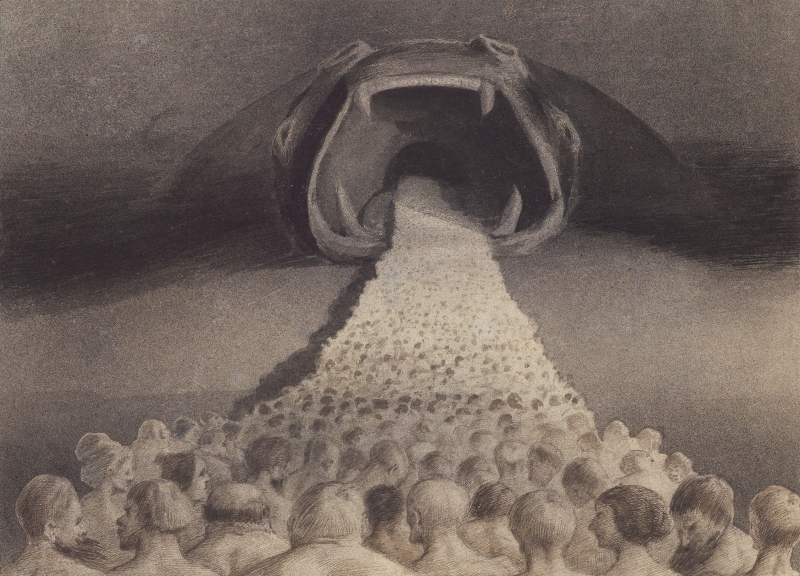

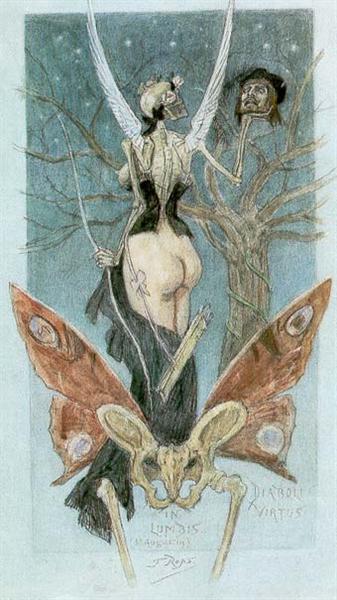

The sheer surrealism of these watercolours tends to distract from the nudity; they seem charmingly silly rather than erotic. Kloos is almost unique in the playfulness of these pictures, but they arguably stand in an identifiable heritage of western European fine art- over and above von Bayros bizarre bestial encounters. Surrealism probably contributed to Kloos’ ideas: for example Dali and, more particularly, Max Ernst, whose collaged novels, Loplop (1930) and Une semaine de bonté (1934) feature strange creatures, often part-human and part-beast. Belgian Symbolists such as Fernand Khnopff and Felicien Rops featured animals as significant presences in some of their images- and we might, perhaps, trace the inspiration all the way back to The Garden of Earthly Delights by Bosch.

Several of the artist’s later works also situated the nudes in exotic environments, from Greek and Egyptian shrines (Aphrodite) through African villages (White Beauties) to eastern temples, thereby also placing Kloos within the orientalist genre. What differentiates Kloos here is that these were purely imaginative works, their far-flung settings merely providing an intriguing backdrop for his figures. Mountains often form the background for his nudes too, obviously not a familiar feature in the Low Countries (see, for example, Meisje In Weiland, Springende Meisjes, Meisjes In De Wei, Meisje In Weide Met Huis, Liggend Meisje Met Koe or Meisje en Schapen). The scenery creates interest but probably adds little to the message of the pictures; their titles, however, tend to confirm that “meisje fascinatie” we saw attributed to the artist earlier.

All in all, Cornelis Kloos’ oeuvre is distinctive. There is much that seems uniquely personal to him, yet many aspects of his work locate him within wider trends of contemporary art as well as within European painting heritage. He is instructive about prevalent trends and themes amongst painters and illustrators during the early twentieth century, shedding light on the parallel tendencies in book illustration, which we have seen played out in the responses of artists to the work of Pierre Louys, Verlaine, Apollinaire, de Sade and others.