As I have described previously, as well as being an author, Pierre Louys (1875-1925) was something of a visual artist- and a collector and connoisseur of art. He collected classical and modern sculptures, being a friend of Rodin, and wrote on the subject in journals. He was a skilled photographer and took pictures (as well as making drawings) of nude women, a few of which survive.

The author’s knowledge of classical sculpture, as well as of the period’s literature, seems to have fed into his writing. For the ancient Greeks- and their imitators, the Romans- the perfect human body represented an ideal that symbolised the Olympian gods. These ideas, and examples of their work, came to shape Western European concepts of beauty and the highest art from the period of the ‘Renaissance’ in classical art and learning, as a result of which life drawing became a fundamental element of an artistic education in the academies. Louys reflected these principles, but he had other reasons for depicting nude sculptures as well.

An initial, small, example will give some idea of the other messages that Louys may have wished to convey through reference to figurative art. At the conclusion of Les Aventures du Roi Pausole (1900) the two young lovers meet in the Royal Park, under the statue of Felicien Rops (1833-98). It may be surprising that this Mediterranean kingdom has erected a monument to the recently deceased Belgian artist, but his highly erotic paintings and engravings of nude women seem perfectly suited to the relaxed atmosphere of the kingdom, which celebrates sex and sexuality as natural and praiseworthy. It is a small joke, or hint, by the writer, indicating his broader attitudes. Earlier in the book, too, Princess Aline has an assignation with the dancer Mirabelle beneath a statue in the royal gardens. This is a fountain known as the Mirror of the Nymphs, above which are “entwined two marble nymphs;” I suspect that this pair are intended as a symbol or reflection of the fact that the pair are about to elope and become lovers.

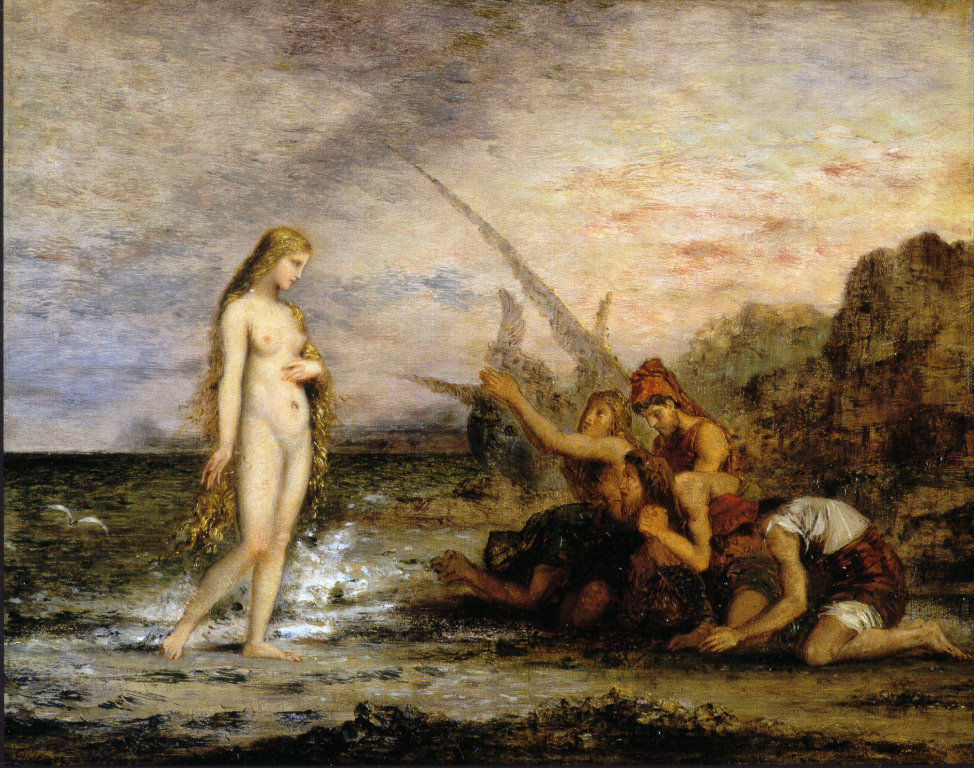

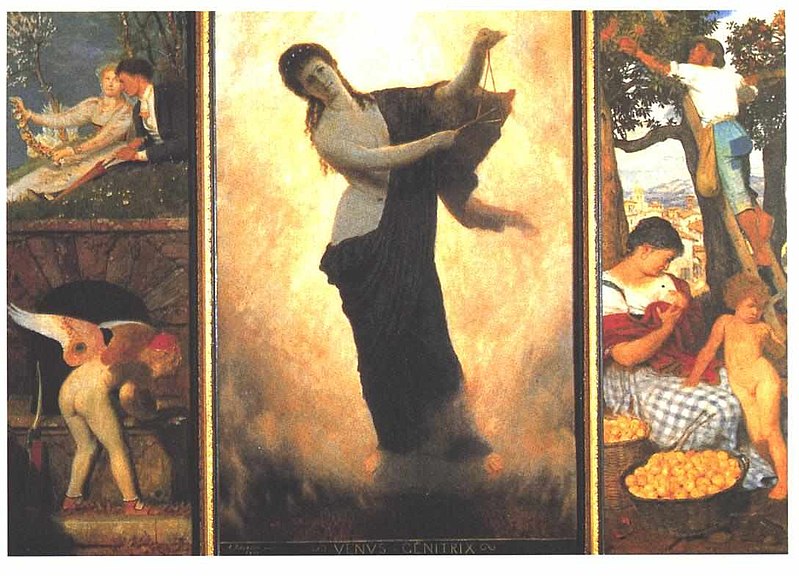

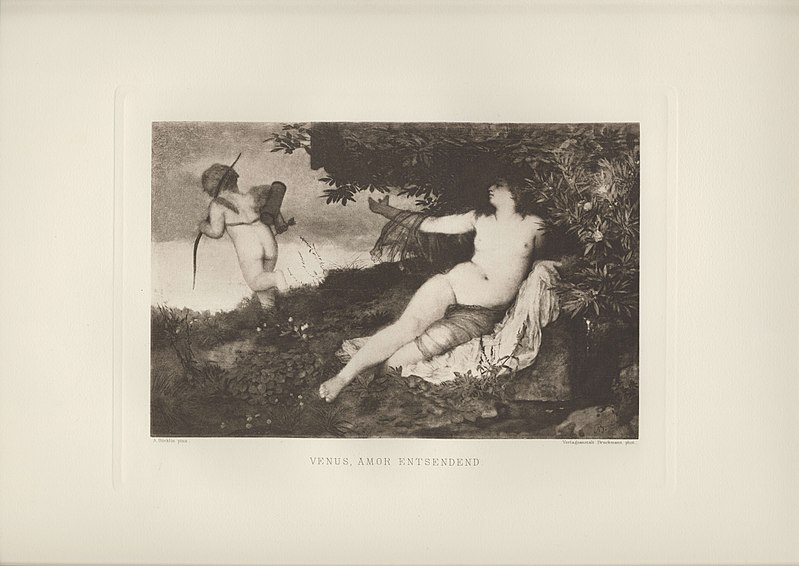

Sculpture and statuary play a major role in Pierre Louys’ second novel, Aphrodite (1896). Louys effectively framed this work with two sculptures. The first represents the goddess Astarte/ Aphrodite and has been modelled upon the young queen of Egypt herself, Berenice, by a handsome Greek sculptor, Demetrios. He partakes of some of the characteristics of the historical sculptor Praxiteles, whose statue of the Aphrodite of Knidos is famed and of which Louys wrote “you were born from the senses of Praxiteles” (‘Aphrodite’ in Stanzas).

“The statue of Aphrodite was… the highest realisation of the queen’s beauty; all the idealism it was possible to read into the supple lines of her body, Demetrios had evoked from the marble, and from that day onward he imagined that no other woman on earth would ever attain to the level of his dream. His statue became the object of his passion. He adored it only, and madly divorced from the flesh the supreme idea of the goddess, all the more immaterial because he had attached it to life.”

Aphrodite, Book 1, c.3

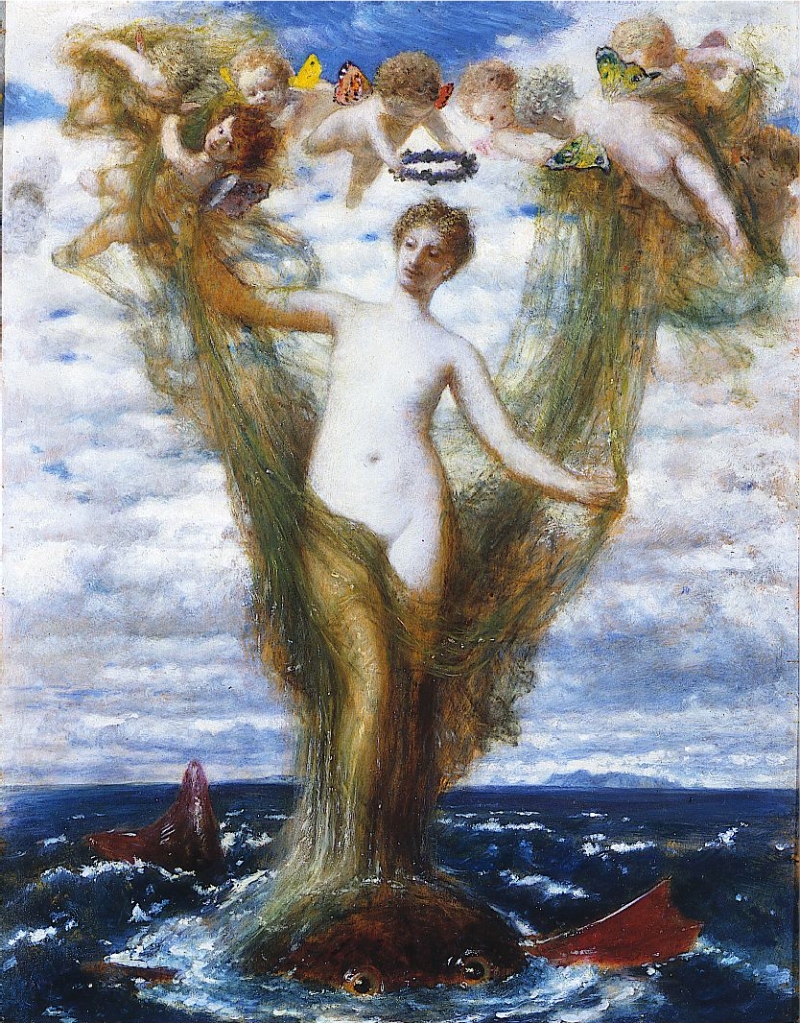

Demetrios has become the queen’s lover whilst sculpting her naked, but he now finds her inferior to the ideal beauty he has created: “The arms of the Other were more slender, her breast more finely cut, her hips narrower than those of the Real one. The latter did not possess the three furrows of the groins, thin as lines, that he had graved upon the marble.” He tires of Berenice and takes multiple other lovers, but none can compete with his own work, now set up in the shrine of the goddess at the heart of the city. Like Pygmalion, the mythical sculptor who falls in love with his own statue, Demetrios goes to the temple to commune with his creation: “O divine sister!’ he would say. ‘O flowered one! O transfigured one! You are no longer the little Asiatic woman whom I made your unworthy model. You are her immortal idea, the terrestrial soul of Astarte, the mother of her race. You shone in her blazing eyes, you burned in her sombre lips, you swooned in her soft hands, you gaped in her great breasts, you strained in entwining legs, long ago, before your birth… I have seen you, evolved you, caught you, O marvellous Cytherea! It is not to your image, it is to yourself that I have given your mirror, and yourself that I have covered with pearls, as on the day when you were born of the fiery heaven and the laughing foam of the sea, like the dew-steeped dawn, and escorted with acclamations by blue tritons to the shores of Cyprus.’”

Demetrios now dreams of other sculptures he wishes to create: “Beautiful feminine forms took shape in his brain… it was distasteful to his youthful genius to copy conventions… Ah! how beauty had once more taken him for its own! how he was escaping from the clutches of love! how he was separating from the flesh the supreme idea of the goddess! In a word, how free he felt!”

It is at this point that Demetrios first encounters the courtesan Chrysis and is overwhelmed by her beauty and the desire to possess her. She resists, consenting only to succumb to him if he steals three treasures for her, one of them being the pearl necklace worn by his own sculpture of Aphrodite. Demetrios is so intoxicated with her that he forgets his wish to be free of the fleshly reality of real women and consents to do what she wants- even committing murder in the process. His theft from the statue of Aphrodite in the temple proves to be an almost erotic event:

“He saw, in a glory of moonbeams, the dazzling figure of the goddess… Demetrios lost himself in ineffable adoration. He believed in very truth that Aphrodite herself was there. He did not recognise his handiwork, for the abyss between what he had been and what he had become was profound… He fixed his eyes upon it, dreading lest the caress of his glance should cause this frail hallucination to dissolve into thin air. He advanced very softly, touched the pink heel with his finger, as if to make sure of the statue’s existence, and, incapable of resisting the powerful attraction it exercised upon him, mounted to its side, laid his hands upon the white shoulders, and gazed into its eyes.

He trembled, he grew faint, he began to laugh with joy. His hands wandered over the naked arms, pressed the hard, cold bust, descended along the legs, caressed the globe of the belly. He hugged this immortality to his breast with all his might… He kissed the bent hand, the round neck, the wave-like throat, the parted marble lips. Then he stepped back to the edge of the pedestal, and, taking the divine arms in his hands, tenderly gazed at the adorable head. The hair was dressed in the Oriental style, and veiled the forehead slightly. The half-closed eyes prolonged themselves in a smile. The lips were parted, as in the swoon of a kiss… The recollection of Chrysis passed before his memory like a vision of grossness. He enumerated all the flaws in her beauty…”

Aphrodite, Book 2, c.4

Despite his impossible conflict between desire for the unattainable love of a marble goddess and a woman who is taking advantage of him, Demetrios carries out the thefts as promised. Triumphant, Chrysis then displays herself, adorned with the stolen treasures, before the people of Alexandria. She is immediately arrested and, for her crimes, is sentenced to death by drinking hemlock. The role of Demetrios in this sacrilege is unknown and he returns to his dreams of sculpting perfect, divine beauty and decides to immortalise Chrysis. He has clay delivered to visit the prison where her body lies:

“Chrysis’ face had little by little become illumined with the expression of eternity that death dispenses to the eyelids and hair of corpses. In the bluish whiteness of the cheeks, the azure veinlets gave the immobile head the appearance of cold marble… Never, in any light, even in his dreams, had Demetrios seen such superhuman beauty and such a brilliancy of fading skin… [He undressed and positioned the body.] He removed the jewellery “in order not to mar by a single dissonance the pure and complete harmony of feminine nudity. Demetrios cast the dark lump of clay upon the table. He pressed it, kneaded it, lengthened it out into human form… The rough figure took life and precision… When night mounted from the earth and darkened the low chamber, Demetrios had finished the statue. He had it carried to his studio by four slaves. That very evening, by lamplight, he had a block of Parian marble rough-hewed, and a year after that day he was still working at the marble.”

Aphrodite, Book 5, c.3.

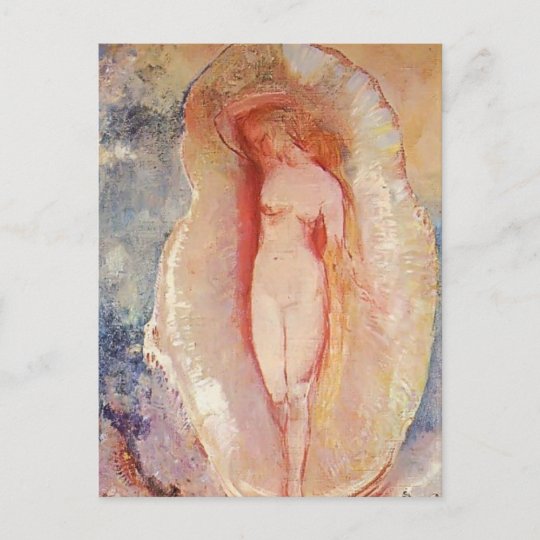

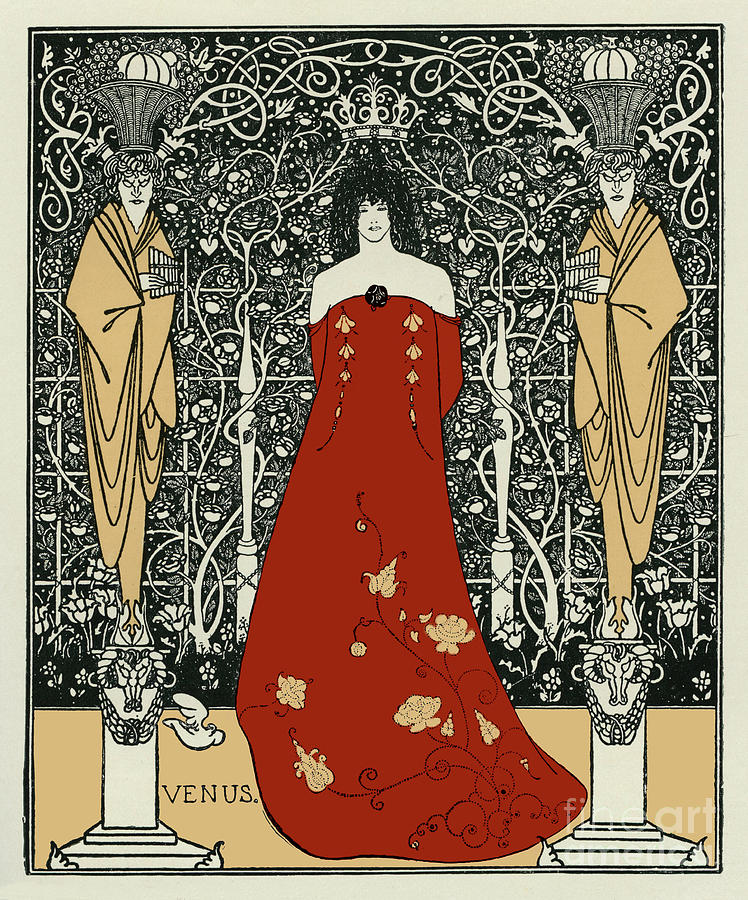

The statutes of Aphrodite and Chrysis are the highest expressions of the sculptor’s art, but they are not the sole functions of images in the ancient world that Louys recreated. Within the precincts of the temple of the goddess in Alexandria, there reside numerous enslaved ‘holy courtesans’ who serve the worshippers. Each woman has a little idol of the goddess that she brought with her from her native country. Some venerate the goddess in symbolic form but most of them have a little statuette, typically a roughly-carved figure that emphasises the breasts and hips. The same kind of little votive effigy is found in Les Chansons de Bilitis. When Bilitis first meets her future wife on Mytilene, she has a terracotta statuette of the goddess around her neck:

“The little guardian Astarte which protects Mnasidika was modelled at Kamiros by a very clever potter. She is as large as your thumb, of fine-ground yellow clay.

Her tresses fall and circle about her narrow shoulders. Her eyes are cut quite widely and her mouth is very small. For she is the All-Beautiful.

Her right hand indicates her delta, which is peppered with tiny holes about her lower belly and along her groins. For she is the All-Lovable.

Her left hand supports her round and heavy breasts. Between her spreading hips swings a large and fertile belly. For she is the Mother-of-All.”

Bilitis, songs 50 & 51

Perhaps it was to such statuettes that Louys referred in his poem Aphrodite when he addressed the “goddess in our arms so tender and so small.” These humble little figures, intended for private rather than public devotions, have a direct personal connection with their worshippers and emphasise the sexuality of the goddess far more explicitly than Demetrios’ noble statue.

The depiction of individual desire and carnality is, arguably, much more the proper function of art in Louys’ novels and poems. The short story The Wearer of Purple (L’Homme de pourpre) which is part of the collection of stories titled Sanguines, published in 1903, tells of the Athenian artist Parrhasius and how he created a famed picture of torments of Prometheus. In addition, though, we hear of him painting an image of a ‘Nymph Surprised,’ that is, being raped, by two satyrs. Parrhasius likes to dash off small pictures of sexual subjects as a form of relaxation, as he tells the narrator of the story, a sculptor called Bryaxis (a name taken by Louys from a real Greek sculptor, who worked around 350BCE):

“I am fond of these pictures dealing with intense emotion and I never represent man’s desire except at the moment of its paroxysm and of its fulfilment. Socrates… wished to see me paint the emotion of sexual love in looks and thoughts. It was an absurd criticism. Painting is design and colour; it only speaks the language of gesture, and the most expressive gesture is that from which its triumph proceeds.”

L’Homme de pourpre, Part 4

In accordance with this, Parrhasius has painted Achilles at the moment of slaying a foe and Prometheus being tortured by an eagle eating his liver. Noble as these works may have been, one suspects that they lacked the impact of the two others we are told about. Besides the ‘Nymph Surprised,’ we hear an account of how the painter Klesides took revenge on Queen Stratonice of Ephesus by means of pictures. She had treated him with dismissive contempt when posing for a portrait she had commissioned from him, so he painted two pictures of her in compromising poses with a man, whom he modelled upon a coarse sailor he had met on the dockside. These were then displayed for all to see on the walls of the palace and huge crowds assembled to enjoy them; the queen had to hide her vengeful rage and pretend to admire the images as well.

It is worth also adding that, in this story, Louys indicates some knowledge of Greek painting. In his Lectures Antiques he had translated the poems of Nossis, in which there are several references to portraiture. Moreover, the author seems to have been aware of developments in ancient artistic techniques. Parrhasius is described, in some detail, creating his pictures with hot wax. He uses a method allegedly employed by the renowned Polygnotus which has recently come back into fashion:

“His little wax boxes were placed in a box already stained with use. He carefully dipped the fine wire heated in the stove, removed a droplet of coloured wax, placed it where he wished and mixed it with the others with a certainty of hand which sometimes made me smile with enthusiasm. [As he proceeds, Parrhasius explains how he pigments the wax.]

Towards the end of the day he stood up, shouting to the apprentices: ‘Heat the plate!’ Turning towards me, he said: ‘It’s finished.’

They brought him the red plate which was throwing off sparks. He grabbed it with long pliers and moved it very slowly in front of the horizontal board, where the wax rose to the surface, fixing its multicoloured soul to the dry wood.”

L’Homme de pourpre, Part 4.

Polygnotus was an artist of the mid-fifth century BCE who is known for having painted various frescoed murals; it is probably his fame that made Louys associate him with the technique of ‘encaustic’ painting. However, it was another Greek artist, Pausias, from the mid-fourth century, who is said to have originated the process; Louys seems to have transferred this to the better known Parrhasius, who flourished before 400BCE. He was famous for his skill and the realism of his works and, after his death, some of his drawings on boards and parchment were preserved as models for other artists. The anecdote about relaxing over obscene paintings was told of Parrhasius, as was a story (relayed by Seneca) that he tortured a slave to death to create an authentic image of Prometheus. Nowadays, we are most familiar with encaustic paintings from the portraits created for mummies in Hellenistic Egypt during the first two centuries CE (see top of page) and, later, from Orthodox Greek icons.

Even more expressly sexual than the figures of Aphrodite is the sculpture created in Louys’ utopian country, L’Île aux dames. On ‘Lesbian Island,’ in the middle of the capital city, erotic statues of women making love are displayed on the Bridge of Sappho that leads onto the island. There, the Museum of Lesbos, naturally, displays erotic statutes and paintings for the delectation of its purely lesbian visitors.

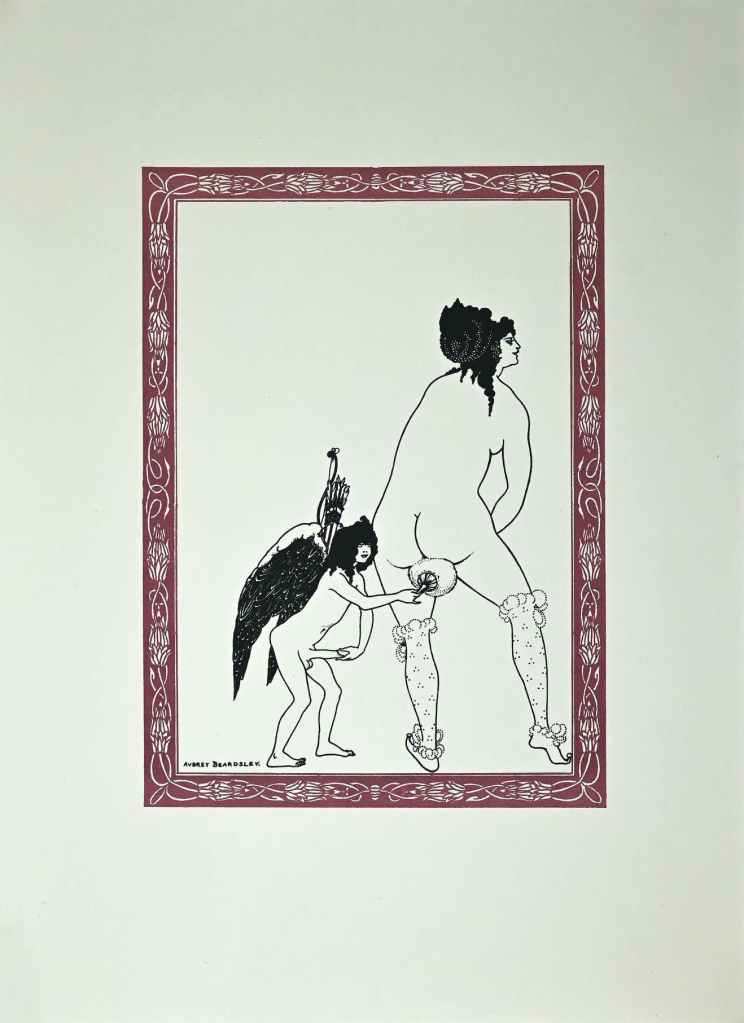

Lastly, the Handbook of Good Manners for Young Girls demonstrates unequivocally how fine art may connect with carnal desires. Here is the advice for polite young ladies visiting a museum:

“Do not climb on the bases of ancient statues to use their virile organs. You must not touch the objects on display; neither with your hands, nor with your bum.

Do not pencil black curls on the pubis of naked Venuses. If the artist represented the goddess without hair, it is because Venus shaved her mound.

Don’t ask the room attendant why ‘The Hermaphrodite’ has balls as well as breasts. This question is not within his competence.”

At the Museum

The final reference is to the famous sculpture now known as the Hermaphrodite endormi, which was discovered in the Baths of Diocletian in Rome in 1618. In 1620 Bernini carved the mattress upon which the figure can now be seen reclining in the Louvre Museum. The Handbook’s second warning has to be understood as a prohibition against defacing museum exhibits; in fact, the Greek habit was to paint their statues to make them more lifelike, a fact of which Louys was well aware and had alluded to it in his description of the statute of Aphrodite as being “lightly tinted like a real woman.”

In summary, art in the works of Pierre Louys exists to evoke the human passions, primarily those of lust and desire. Partly this is because the goddess Aphrodite/ Astarte/ Venus/ Ishtar was worshipped through carnal love; partly because sex and sexuality were regarded as such fundamental aspects of humanity by Louys.

A full, annotated version of this essay can be downloaded from my Academia page.