Vienna at the turn of the last century still retains for us an aura of decadence and bohemianism. This is derived from a number of sources- the famous paintings of Gustav Klimt (and a little later, those of Egon Schiele); the researches of Sigmund Freud into the unconscious and the nature of sexuality; the writing of Felix Salten and his outrageous pretend biography of prostitute Josefine Mutzenbacher.

Another, less well known strand in this aura of fin-de-siecle debauchery must be the art of Franz von Bayros, although his collections of prints are far less well known than the paintings of Klimt and Schiele.

Some artists dare to be as explicit and as provocative as possible. Unquestionably, Franz von Bayros (1866-1924) was one of these. He was a commercial artist, illustrator and painter who is usually classed as part of the Decadent movement and who regularly utilised erotic themes and fantastic imagery. The explicit content of his phantasmagoric erotic illustrations mean that von Bayros is often compared to Félicien Rops and Aubrey Beardsley, yet he is probably more scandalous than either of them. He was often called ‘Marquis Bayros’ in reference to the Marquis de Sade.

Bayros was born into a Spanish noble family in Zagreb, which was at the time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and, aged seventeen, he entered the Vienna Academy, where his friends included Johann Strauss. After the breakdown of a marriage, Bayros moved to Munich to continue his art studies. He subsequently travelled and exhibited widely in Europe, staging his first exhibition of work in 1904. Thereafter, he embarked upon a career illustrating books, particularly those with an erotic content, such as Fanny Hill which was published in 1906. He also designed portfolios of his own erotic fantasy art. In 1911 Bayros published his most famous and controversial work, the portfolio Erzählungen am Toilettentische (Tales from the Dressing Table). This collection featured extensive scenes of lesbian bondage, group sex, and sado-masochism- themes that dominate his entire output. It was possibly unsurprising that he was later arrested and prosecuted by the state censor, leading to his exile from Germany. He returned to Vienna, but felt increasingly depressed and alienated.

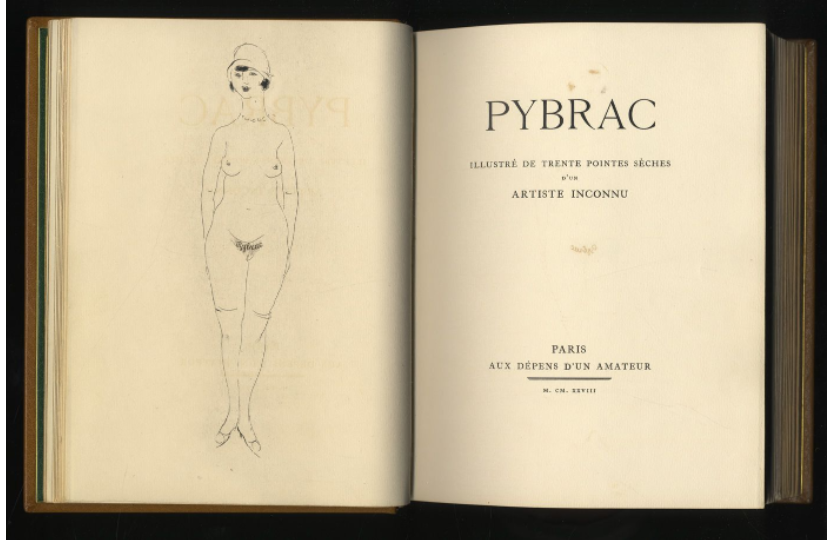

Von Bayros produced a stream of erotic prints (albeit in quite limited editions) during the first decades of the twentieth century. These began with the 1905 collection Fleurettens Purpurschnecke (‘Fleurette’s Purple Snail- Songs and Poems from the Eighteenth Century’), a limited-edition portfolio of black and white drawings illustrating eighteenth century ‘Erotische Lieder und Gedichte’ (Erotic Poems and Stories).

In 1907 he issued four collections- the Geschichten aus Aretino (Stories from Aretino) of fifteen engravings; Die hübsche Andalusierin (The Pretty Andalucian Girl), which follows the sexual life of a woman called Aldonza; Die Grenouillère, the French title of which refers to a one-piece pyjama suit but has the sense of the English colloquial ‘birthday suit’- in other words, nudity; and Die Bonbonnière (The Box of Sweets), comprising two portfolios of six prints each, the etchings being accompanied by short poems.

Erzählungen am Toilettentische was published under the name of ‘Choisy le Conin’, which von Bayros had adopted for the French market- partly to appeal to a Francophone public and partly to conceal his true identity. However, the cover of the collection stated his true name, leading to the censorship action in Munich over the sexual content. The Geschichte der Zairette, also released in 1911, likewise includes a high degree of adult lesbian erotica.

Bilder aus dem Boudoir der Madame CC (Pictures from the Boudoir of Madame CC), was privately published in 1912 and was a collection of thirty existing etchings, brought together under a suggestive title. The images include a mix of heterosexual and lesbian activity with a good deal of fetish bondage. Im Garten der Aphrodite (In Aphrodite’s Garden) was a portfolio from 1910 comprising eighteen etchings which was published at the same time as Bilder aus dem Boudoir and shared nine images with it. It largely depicts adult women seducing younger girls. Finally, Lesbischer Reigen (Lesbian Roundelay) was published in 1920. It was von Bayros’ last erotic portfolio, comprising just six etchings, and shows adult female couples. Von Bayros’ work for private clients is also highly enlightening. He was commissioned to design numerous ex libris book plates, and these were uniformly erotic in content. Inevitably, his clients shared his strange erotic tastes: for example, Stephan Kellner’s 1910 library plate pictures a girl crouching naked in front of a large snake.

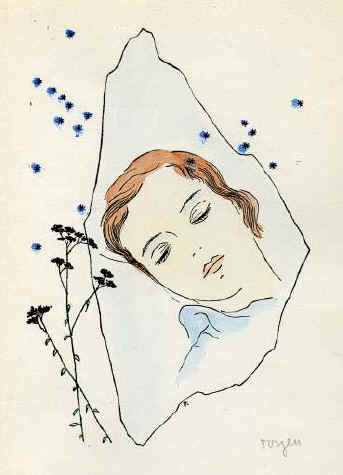

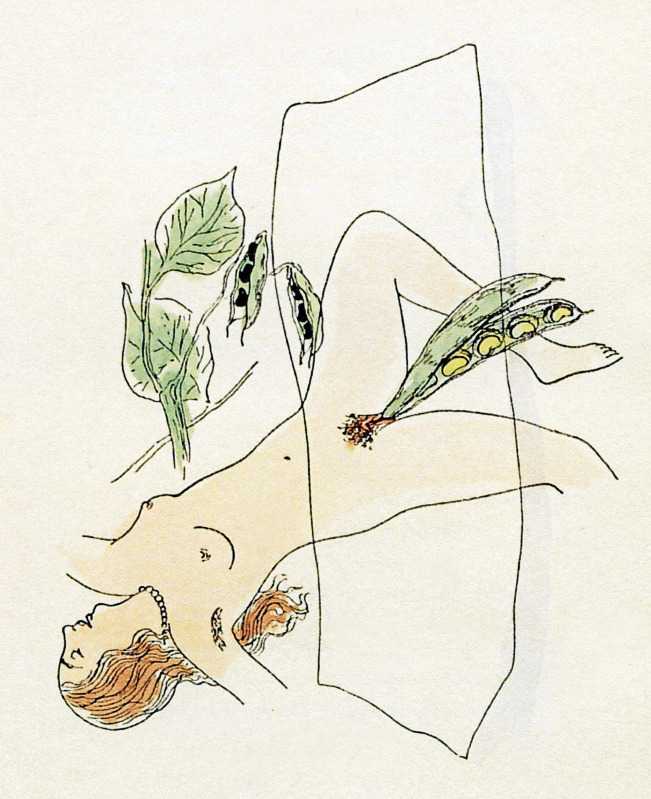

Another late work by von Bayros is the three volume Bayros Mappe set, published in about 1920. It returns to book illustration, with one volume focused upon the legend of Isolde and another comprising six coloured drawings on the subject of Salome, a Decadent favourite. He then illustrated Dante’s Divine Comedy in 1921, not a surprising choice perhaps. Sinnlicher Reigen– ‘Sensual Dance (Pan)’- is another colour image of the same date as the Bayros Mappe. It is a more typically bizarre von Bayros scene, which is taking place in the porch of an elegant house. The focus is Pan, a huge hooved figure, who is dancing arms linked with two women. One is fully clothed in black, including a hat and coat, and is rather calm and static; the other is naked except for her white high heels and is cavorting excitedly. In the foreground, with her back to us, is a young plump fauness, naked and with her golden hair in a bun. The juxtapositions of clothed and naked, young and old, human and mythical, coupled with an ambiguous atmosphere of sensuality, are typical of the artist. You are often unsure whether we are witnessing scenes in the real world or in some sort of febrile dream.

While von Bayros had risen to the highest cultural and artistic circles in Munich, it was difficult for him to re-establish himself in Vienna. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 prevented a long-planned for emigration to Rome. The defeat and collapse of Germany and Austria in 1918 led to severe depressions in the last years of his life. Although he enjoyed considerable success with his beautiful watercolour illustrations for the Divine Comedy, the work on the drawings exhausted him both physically and mentally. Devaluation of the Austrian currency added to his problems and von Bayros died in poverty in Vienna in 1924. One of his very last publications, a portfolio of sixteen prints issued in 1925 under the name of the Chevalier de Bouval, is typical of von Bayros’ entire output: it features solely women, seen occasionally alone but usually in pairs in bedrooms, where they engage in a range of more or less unusual practices together. The engravings are all completed in the artist’s typical style of very fine penwork, attention to detail and rich depiction of fabrics- whether voluminous lacy dresses or the cushions upon which the figures recline.

The reputation of Von Bayros has risen in recent decades as there has been a rediscovery of his weird and decadent art. He has been praised for “the bizarre sexual anarchy that he created in the sedate and decorous boudoirs of the early 1900s. Powerful females populate his exquisite, beautifully detailed drawings where sexual perversity is rife, and the byword is luxurious decadence.” The world that von Bayros imagined was radically at odds with the bourgeois society he knew and whose members purchased his works. His women seem to be part of that world, yet they actually inhabit a parallel existence where men are largely absent and strange fetishes and practices dominate. I think that, alongside the clear eroticism of von Bayros’ work, there is also a strand of bizarre humour, an element which must be considered when assessing the overall tone of his work.

The work of von Bayros may profitably be compared to that of the closely contemporary Martin van Maële. The latter’s collection of forty drawings, La Grande Danse macabre des vifs, was published in Brussels in 1905 by erotic specialist Charles Carrington. This ‘dance macabre’ examined in frank, if blackly comedic, detail a wide range of sexual preferences, including juvenile explorations, rape, oral sex, lesbian encounters and age-discrepant desire. In very many respects, van Maële’s baroque and uninhibited fantasies parallel the contemporary erotic visions of von Bayros. Both reveal something of the psyche of the age, crystallising or laying bare attitudes and appetites which were generally hidden but which, in visual form, were far less mediated or disguised.

I have refrained from reproducing illustrations from the portfolios such as Erzählungen am Toilettentische and Im Garten der Aphrodite, but von Bayros’ work is readily available online, from art and antique dealers and book sellers, and from Amazon and the like in the form of collections of his pictures. For more discussion of the works of von Bayros in their wider context, see my book In the Garden of Eros, available as a paperback and Kindle e-book from Amazon.