In 1975, the artist, lecturer and art historian Peter Webb wrote about the work of the Austrian illustrator Franz von Bayros, describing his illustrations of erotic literature and his “skilful drawings that reflected fin-de-siecle extravagance and showed a great debt to Aubrey Beardsley. He conjured up a world of guiltless sex, a carefree world of sexual pleasure only occasionally marred by harsher realities.” Von Bayros’ inspiration by Beardsley (as well- to a lesser extent- by Felicien Rops) is clear, but it struck me recently, when working on my study In the Garden of Eros, how their influences might also be traced to Jean Traynier, illustrator of Cydalise by Pierre Louys.

Aubrey Beardsley was a self-taught artist who had learned his craft from studying illustrated books and ancient Greek painted vases. He was inspired and encouraged by Edward Burne-Jones, but (as Edward Lucie-Smith wrote in Symbolist Art) the young man emphasised what was perverse in the older painter’s work. Beardsley is known for his sharp penwork, his “linear arabesque,” which he balanced against bold contrasts of black and white. Lucie Smith described how Beardsley was a natural illustrator, able to “think of the design as something written on a surface, whose essential flatness must be preserved in order to balance the type which appear either on the same page or on a facing page.” He was a founder of the Art Nouveau style, hugely influential across Europe, and, through his work, book illustration came to be dominated by the new Symbolist and Art Nouveau ideas: “Partly art and partly craft, illustration rapidly assimilated itself” to the new decorative movement- as we have seen, for example, with Henri Caruchet.

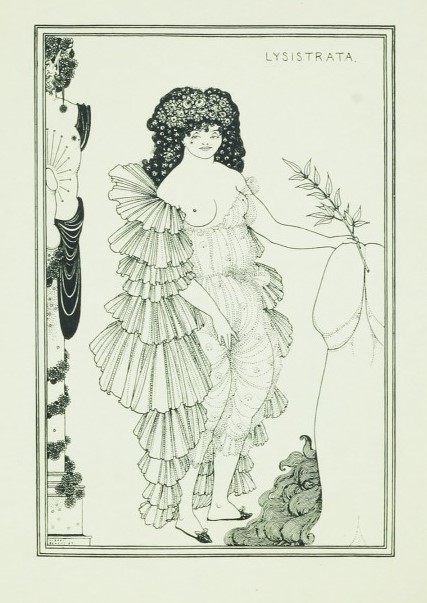

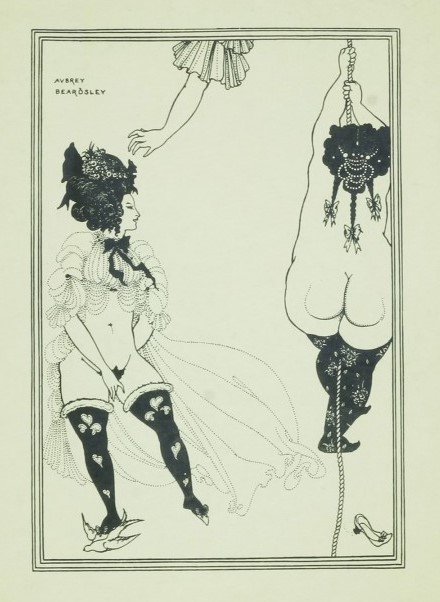

Beardsley is renowned for the highly erotic nature of much of his illustration. His work on Aristophanes’ play Lysistrata (1905) is characterised, in particular, by men caricatured with enormous phalluses and, quite commonly, large, mature women with big bosoms and bottoms. He depicted sexuality and bodily functions with a startling honesty that offended many at the time. Webb was perfectly correct to spot the lineal influence, for the work of von Bayros bears many close parallels with that of Beardsley: not only is his sharp graphic work comparable (both artists depicted fabrics in a masterly fashion), but there are the exaggerated phalli (which may also be found in Rops), the obese and lascivious women, the preternatural and precocious children, and (even) in one plate, from his collection Im Garten der Aphrodite, a scene in which woman ecstatically rubs herself along a taut rope (something which instantly reminded me of the engraving of ‘Two Athenian women in distress’ from Lysistrata reproduced above). Odd forms of excitement like this are typical of the illustrator’s images: compare as well ‘Le Collier‘ (The Necklace) from von Bayros’ portfolio of 16 prints produced under the pseudonym of Chevalier de Bouval in about 1925.

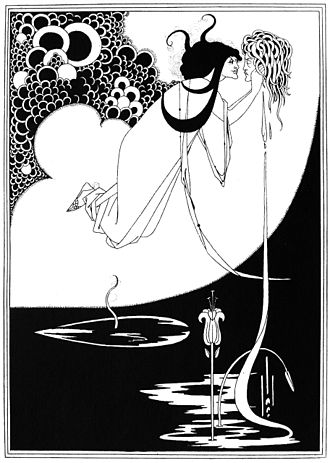

Both Beardsley and von Bayros illustrated Salome and John the Baptist- in the case of Beardsley, for Oscar Wilde’s play Salome (1896). Each artist also detected and portrayed something unwholesomely sexual in the relationship between the princess and the executed prophet- in one plate by von Bayros he showed Salome breast-feeding the severed head of the Baptist, which lies on a plate. Decapitated heads and skulls were, in fact, common in the Austrian’s’ work, another part of the cloying atmosphere of macabre perversity that he constructed.

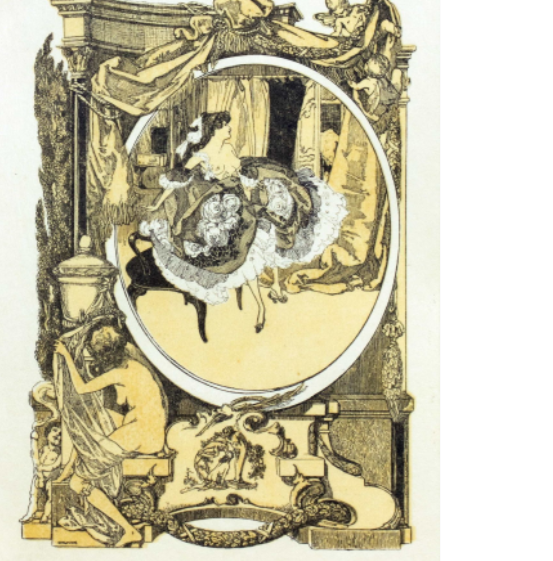

These two earlier artists seem to have provided clear models for Jean Traynier when he came to taking on erotic works such as Louys’ Cydalise in 1949 and a 1957 edition of Point de Lendemain, ou la nuit merveilleuse (No Tomorrow, or the Wonderful Night) by Dominique-Vivant Denon (1747-1825). In the case of the latter, the eighteenth century setting reminds me of many works by von Bayros, such as his 1905 portfolio Fleurettens Purpurschnecke- Erotische Lieder und Gedichte (Fleurette’s Purple Snail- Erotic Songs and Poems from the Eighteenth Century) and John Cleland’s novel, Die Memoiren der Fanny Hill (1906). In part, these images simply mirror the era of the works being illustrated, but their erotic nature (and that of other writers such as Laclos and de Sade) generally imparted an aura of licentiousness to the entire period- so that wigs and beauty spots came to act as visual symbols for a certain liberated sexuality: Beardsley’s plates for The Rape of the Lock, as well as the general mood of his Lysistrata, are cases in point; in addition, see my book, Voyage to the Isle of Venus.

As for Traynier’s monochrome engravings for Cydalise, two of the plates feature exaggerated, ‘fantasy’ phalli directly comparable to those seen in Lysistrata, and surely inspired by them, possibly by way of either von Bayros or Rops- or just as likely directly. Comparable ‘erotic dream’ images, albeit in very different styles, may be found in the 1932 edition of Pybrac by the Czech surrealist Toyen and in recent work by the British graphic artist Trevor Brown. In addition, the black and white style adopted for both works by Traynier repeats that of von Bayros and Beardsley, suggesting that, for him, it seemed suitable for depicting powerfully erotic scenes. Another small detail which may indicate a derivation from Beardsley’s Lysistrata are the many bows the decorate the hair of Traynier’s female figures- an elaborate and distinctive touch.

The influence of von Bayros might also be traced in similar details. I have discussed previously the pseudonymous erotic illustrator Fameni Leporini. The impact of Claude Bornet’s 1790s illustrations to de Sade seems clear, as both opt for naked bodies stacked up improbably in their renderings of orgies, but the morbid mood of von Bayros may also be detected. Leporini, too, preferred pen and ink for his designs and we may identify in them various traits and details that appear to have been borrowed from the Austrian: the mood of perverse cruelty and of lesbian passion that suffuses a good deal of his work and certain specific scenes which could be derived more directly from examples by von Bayros.