Léon-Jean-Bazile Perrault (1832-1908 ) was French artist who catered to affluent bourgeois taste by producing beautiful pictures to decorate their homes. Inspired by his teachers, François-Édouard Picot and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, who were both master painters in the Academic style of the nineteenth-century, Perrault perpetuated their emphasis upon mythology and idealisation. Like them, too, Perrault drew upon the eighteenth century artistic tradition of painters such as Jean-Antoine Watteau and François Boucher, who both painted idealised subjects as well.

Léon-Bazille Perrault was born to a poor family in Poitiers. At the age of fourteen he began drawing lessons as a way of earning extra income for the household; he displayed considerable talent and was soon helping to renovate local churches. Winning a drawing competition when he was 19 enabled Perrault to afford to travel to Paris to begin his formal artistic training, which began under Picot and was continued with studies under his friend Bouguereau at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Like Munier before him, Perrault was deeply inspired by his teacher and the latter painter’s influence certainly shows in their shared style and subjects.

Perrault’s career began during the Second Empire of Napoleon III. This was a period marked by a middle class taste for works of art that were superficially beautiful rather than intellectually demanding or avantgarde. Painters such as Perrault, Bouguereau, Cabanel and Munier all supplied that market. Like his contemporaries, Perrault met this commercial demand with mythological figures, pictures of children, nudes and some genre scenes. What proved popular at exhibitions and sold best as either paintings or as engraved reproductions were pictures that offered an idealised version of contemporary life. Nonetheless, these paintings were also awarded prizes at exhibitions; Perrault received a number of awards and professional honours for his work.

Just like Bouguereau and Munier, a very important element in Perrault’s output were his pictures of children. A contemporary article in the magazine The Century described how:

“…it is not extravagant to add that no painter of children, from the time of Albano to the present day, has more perfectly rendered the inner structure and subtle modelling of surface, the peculiar quality and graceful action of a child, in perfect physical beauty and health; and all artists know that children are the most difficult of subjects.”

‘The Child in Art: Perrault’s Le Reveil d’Amour,’ The Century, vol. 46, 1893.

Whether Perrault’s young subjects were depicted playing a game, working in the countryside or were located within some mythological story and setting, they were all highly sentimental images which played upon the Romantic stereotype of childhood: its innocence and vulnerability, prettiness, endearing naughtiness and charming imitations of adult occupations. This can be seen particularly in Perrault’s numerous paintings of sleeping babies, angels, putti and cupids (pursuing a theme already profitably exploited by Bouguereau) or in his images of maternal or sisterly tenderness, which again feature sleeping babies or dependent toddlers and appealed to the same market. Also, like Munier, Perrault played upon his buyers’ parental emotions, as with En penitence (In disgrace) seen above; we as viewers are involved and appealed to by the image: the girl in her pure white shift seeks our comfort for some misdeed. There was, too, shameless sentimentality and schmaltz in the manner of Munier. Perrault painted a number of pictures of girls with cats and kittens, which surely meant to delight and charm in a very cynical way.

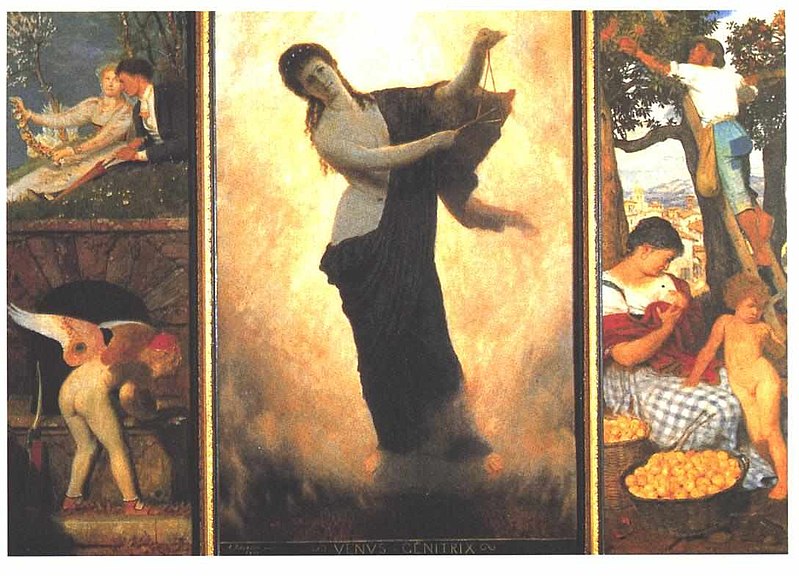

Perrault’s images fitted into the ‘Romantic’ view of the child as pure and innocent, yet he added another layer to this. Just like Bouguereau and Munier, Perrault allowed a hint of adult awareness to creep into his images. Girl with Dove (seen below) is very much in the Greuze style in which the soft vulnerability of the bird is knowingly juxtaposed beside the exposed flesh. The dove is white and pure; her shed shift is white and pure and yet there is an undeniable subtext in the plump bird pressed to the chest. Boucher (mentioned earlier) also did the same in the eighteenth century as in his rather more blatant Venus with Two Doves. Audiences were expected to spot these resonances- which they must have done too in the painting The Education of a Sparrow (1894)- for which, see below. Doubtless, too, Perrault’s At the Fountain was an almost obligatory nod to Greuze’s Broken Pitcher, though sanitised and harmless. We might note as well how similar his girls look to those of his mentor and peer Bouguereau and how- again like his master- the girls are often found perched on convenient blocks of stone.

As with Bouguereau, Perrault’s countryside could be idealised- witness the classical fountain where the girl is filling her jug (above)- but, despite the risk of putting off buyers, he seemed readier to acknowledge the life of toil that poor rural children faced: The Wood Gatherer and The Lumberjack’s Daughter both have heavy burdens to carry. Away from Home (1879) shows a girl with a violin- a street musician- standing outside in the snow; Out in the Cold (1890) depicts a brother and sister shivering on a frosty step in the street (see too Les Jeunes Mendiants). Bouguereau painted very similar subjects, but made them sunny and hopeful. Perrault could be more honest- yet then again, The Apple Picker (1879) and The Snack (1880) make basic country fare look simple and wholesome- rather than indicative of poverty- which the girls’ lack of shoes implies.

Equally, despite the occasional hints that a living has to be earned, there is also plentiful time for picturesque and endearing play, by the sea or by pools, as we see in After the Swim (above), in which the little girl has gathered a bouquet and crosses her feet in an endearingly awkward manner. Like Bouguereau, Perrault often painted gypsy girls, and they are rendered as exotic and colourful creatures, wearing distinctive costumes and introducing an orientalist element into his work. Unlike Bouguereau, though, his subjects far less often engage with the viewer in a knowing two way exchange (although see Girl with Kittens). His master would have exploited far more the opportunities for suggestiveness presented by the hints of bared flesh in The Mirror of Nature, Crossing the Stream or The Wood Gatherer. Instead, for Perrault white dresses or blouses and flowers stress the Romantic notions of natural and pure innocence (Spring or A Crown of Flowers).

For more information on Victorian era art, see details of my book Cherry Ripe on my publications page.

To summarise, Perrault was described in the 1893 article in The Century as “a polished French gentleman… suave and affable in his manner, tall and vigorous, a serious worker… his studio is richly and picturesquely furnished, after the usual luxurious manner of successful Parisian artists. It is, however, not a place of leisure, for Perrault is one of those modern painters who do their ten hours a day of hard work. He was the air of a well-to-do, practical man of the world.” He had learned the work ethic of his mentor Bouguereau and had realised that long days at the easel, giving the public what the public wanted, meant commercial success.

See too my book on nineteenth century painting on the books page.