In the course of researching my recent posting on Sound and Vision and the art of illustrating literary texts, I turned up a handful of new artists who were not previously familiar to me; all worked on Pierre Louys’ second novel, Aphrodite, and deserve a mention.

Edmond Malassis was one of the earliest illustrators of the book (1896- reprinted 1898); for brightness of colour and sheer energy of his plates and headpieces, I prefer his work to that of Antoine Calbet or Edouard Zier. His street scene is alive with gossip, rumour and sly seductive looks; the episode in which Chrysis discovers Rhodis and Myrtocleia in her bed is accurately portrayed- the young courtesan initially forgetting that she has company because she is so obsessed with her own appearance.

Perhaps the most interesting is Jean-Andre Cante (1912-77) who was a painter, sculptor, engraver and architect. He was a student at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Bordeaux between 1927 and 1934 and then worked as an illustrator until 1948. After this time, he became a teacher at the school of Applied Arts in Paris, whilst also switching his attention to new techniques for integrating works of art into concrete architecture. As a technician and researcher, he developed new materials to achieve this, in particular synthetic resins combined with polystyrene or polyvinyl chloride. His illustrative work is very pleasing and pretty, as in the cover image for an edition of Louys’ Aphrodite (above), from 1949. Reverting to the discussion of that earlier post, we see here the Ephesian flute players, Rhodis and Myrtocleia, depicted exactly as the Pierre Louys must have imagined them.

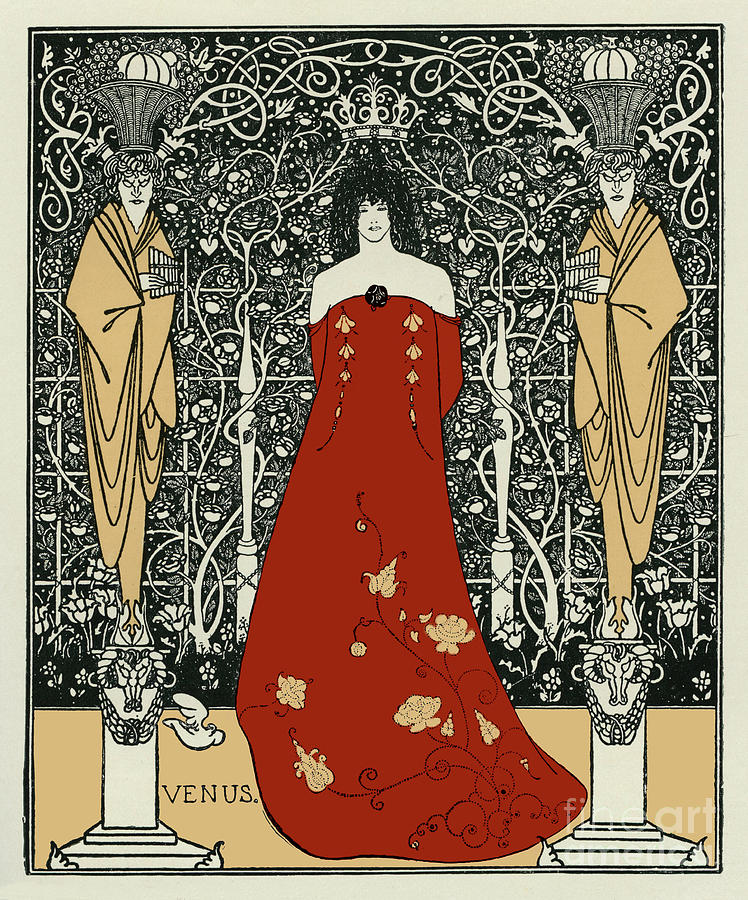

Pierre Rousseau (1903-91) was an illustrator and official French army painter. Amongst the works he illustrated were various literary and ‘adult’ titles, such as Flaubert’s Madame Bovary in 1927, an edition of Restif de la Bretonne in 1928, Alphonse Daudet’s Sapho (1929), Baudelaire’s Spleen in 1947 and Prosper Merimee’s Les ames de purgatoire in 1946. He also worked on numerous children’s books. In 1941 Rousseau illustrated a life of Marshall Petain that was, essentially, propaganda for the French regime then ruling that part of France not occupied by the Germans. It has to be noted that several of the contemporary writers whose works Rousseau illustrated during this period collaborated with the Nazis. Nevertheless, his work on Louys’ Aphrodite in 1929 is beautiful, with its use of simple blocks of colour and bold design. As can be seen below, in the image heading chapter 7 of Book 1 of the novel, Rousseau appreciated that there was little difference in age between Chrysis and the two Ephesian musicians, Rhodis and Myrtocleia, and in his illustration, he was faithful to the text by Louys.

Firmin Maglin (1867-1946) was a French painter and lithographer. He trained at two drawing schools in Paris and began exhibiting his work at the Salon of French Artists in 1890, at the Salon des Indépendants in 1895 and at the Salon d’Automne in 1903 and 1904. His paintings are mainly landscapes in a post-impressionist style, but he also produced orientalist work (such as Le Harem in 1935 and Les Jardins du Serail– The Gardens of the Seraglio). Maglin also designed lithographed illustrations for works of literature, supplying twelve engravings for an edition of Aphrodite in 1930: as noted before, these are in a rather dated style, although with a certain lively charm. The artist was rather older than the other illustrators discussed here and I suspect that he depicted the women in the styles of his youth, their hair piled on their heads as would have been fashionable around the turn of the century. His nudes remind me of another French artist of the same generation, Georges Picard (1857-1946), whose nymphs and faeries likewise looked like society ladies accidentally naked in the wrong surroundings. The ‘orgy’ scene below is notable for several reasons: in the background you can just about spot Rhodis and Myrtocleia providing the music, whilst the krater full to the brim with red wine in the foreground indicates how wild things might get later… (They do- in several ways: the musician Rhodis’ sister Theano, who’s a dancer, is dipped head first in the wine before being seduced- and then a slave is crucified).

A further- and apparently very commercially successful- edition of Aphrodite was published in 1931 by Carteret. The illustrator was Maurice Ray (1863-1938), a successful painter and illustrator who worked in a variety of styles, most notably producing nude and semi-nude female figures in Neoclassical and Orientalist (Egyptian) settings. This ideally suited him to work on Louys’ second book and he captured the decadent atmosphere very well- although we may remark how he has raised the ages of Rhodis and Myrtocleia in the plate shown below. The success of this edition of the book may well be ascribed to its plentiful illustration, for it included 32 watercolours by Ray along with twenty-five woodcuts taken from his designs by a Madame Moro-Ruffe.

In 1936 the artist Andre-Edouard Marty (1882-1974) worked on a further edition of Aphrodite. He was also later to produce some striking illustrations to Les Chansons de Bilitis. His work on Louys’ second novel is characterised by its bold art deco style and beautiful colouring. His strong lines and bright tones doubtless explain why Marty was also commissioned to design posters for the London Underground in 1933.

The Second World War caused a hiatus in a lot of publishing for obvious reasons, although I suspect that in occupied Europe the book trade discovered that the Wehrmacht offered an active market for some products- both the fine art and more trashy erotica. This may partly explain why in 1944 a new edition of Aphrodite appeared in Brussels, with an illustrated and coloured title page and fifteen plates designed by Renée Ringel. She was a prolific illustrator of books, from children’s works (Les plaisirs et les jeux, 1940) through to adult texts (such as Collette’s Claudine books and Ovid’s L’Art d’Aimer, ‘The Art of Love,’ also 1950- a title notable for featuring a lesbian couple on its title page). Ringel had an extremely attractive style, highly reminiscent of Mariette Lydis, or perhaps Suzanne Ballivet; sadly, I’ve been unable even to discover dates for her, although she was active during the 1940s and ’50s. The similarity between women Ringel drew and those of Lydis- as well as her focus upon the female characters in the book, lead me to suspect that she too was lesbian or bisexual. For example, the feast and bacchanal staged in part three of the book is, in the text, a mixed affair, but Ringel makes it look like a solely female orgia.

There’s also some indication that (like Edouard Zier before her), Ringel was influenced by Antoine Calbet’s 1896 edition of the book. We are told by Louys, very much in passing, that part of the reason that the story’s heroine, Chrysis, ran away from home aged twelve, and became a courtesan in Alexandria, is because her mother had been so protective of her, shutting up inside whilst other “little girls bathed in a limpid brook [near the house] where one found red shells under the tufts of laurel blossom.” Calbet turned this tiny mention into an illustration in the text; Ringel chose the same minor biographical detail and produced a very similar image. As with Zier’s image of Melitta with her mother, this seems to me to be more than just a coincidence but a deliberate homage.

Lastly, the artist calling himself Morin-Jean (1877-1940) also worked on an edition of Aphrodite in 1947. Morin-Jean initially studied law but switched to become an artist in 1911. Amongst his other illustrative work was an edition of Flaubert’s Salammbo (1931). His woodblock engravings are highly distinctive, their bold outlines being appropriate to the ‘antique’ subject matter, and the colour covers are simple but striking.

Once again, I feel that these designs indicate how good illustrations can enhance and add additional layers of meaning to the text that they complement. They are, in their own small way, a gesamtkunstwerk, a complete work of art in which media are combined to create a single, cohesive whole (one of the earliest literary examples might be the Almanac of the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) group in 1912). Theory aside, the pleasure of a beautifully designed volume hardly needs to be described or proved; there have been numerous illustrated editions of Aphrodite, one of the most popular popular books that Louys wrote, and these continue to be highly sought after by collectors (as most of my illustrations here show, as they are taken from various dealers’ websites). Books like these have to be appreciated as a whole, experiencing the plates alongside the story and enjoying their interaction in the imagination.

For a complete discussion of the illustrated editions of the works of Pierre Louys in their wider context, see my book In the Garden of Eros, available as a paperback and Kindle e-book from Amazon.