As some readers of this blog may already be aware, I also write the British fairies blog on WordPress. This latest posting sits somewhere between my two sites, but as it takes a more pragmatic and non-folklore perspective, I put it here.

If you’re determined to find a rationalising and ‘psychological’ explanation for the belief in fairies, a fruitful approach may be to view them from the perspective of the British landscape. It’s arguable that they are a medium for representing aspects of the land and climate. One way of explaining the fairy faith is to see it as a way of articulating what’s sometimes called the genius loci- the spirit of place- that people have sensed over the centuries in particular places.

Paul Nash, Earth home, or The fortress

Spirits of place

Many British writers and artists have responded in mystic fashion to the British landscape. The landscape visions of William Blake and Samuel Palmer were shared by later artists, especially by Paul Nash. His writings disclose a strong sense of the unique character of places and the power of those with links to antiquity. Of Wittenham Clumps, which he painted repeatedly, he said:

“I felt their importance long before I knew their history… [The landscape was] full of strange enchantment, on every hand it seemed a beautiful, legendary country, haunted by old gods long forgotten.”

Later in his life, Nash encountered the stones of Avebury. Writing in Country Life in May 1937, on The Life of the Inanimate Object, he explained that “it is not a question of a particular stone being the house of the spirit- the stone itself has its spirit, it is alive.” This idea of animating inanimate objects was very old indeed, “a commonplace in fairy tale and and occurs quite naturally also in most mythologies.” Sketching at Silbury Hill near Avebury, he recalled that-

“I felt that I had divined the secret of that paradoxical pyramid. Such things do happen in England, quite naturally, but they are not recognised for what they are- the true yield of the land, indeed, but also works of art; identical with the intimate spirit inhabiting these gentle fields, yet not the work of chance or the elements, but directed by an intelligent purpose ruled by an authentic vision.”

For Nash there was magic in ancient and significant places that was still real and tangible, even in the mid-twentieth century. His art tried to express and to contact those deep forces of the English landscape.

Paul Nash, Silbury Hill

In traditional folklore, some fairies have been inextricably linked to specific locations. The brownies are the best example, being tied to an individual farm or dwelling, but spirits might also be associated with particular natural features- caves, pools, groves or fords, for instance. Morgan Daimler in her recent book Fairies called these ‘land spirits.’

The intimate associations with certain landscape features has encouraged writers to speculate upon the nature and role of these beings. In her book Faerycraft Emily Carding describes fairies as nature spirits of place who are “the inhabitants and guardians of the inner landscape of our world, just as we are of the outer landscape.” They are “the spiritual life force within the land.” In Sirona Knight’s conception, “the strength of fairies comes directly from the power of the land. The generations buried in the land give it tremendous sacred power. This sacred power is the power of the fairies.” (Faery magick, c.1) Other writers have linked the fays to ley lines; they are ancient spirits magically tied to certain places of the earth.

David Inshaw, Silbury by night.

‘These gentle fields‘- the personality of the land

Fairies may equally be a means of expressing the particular landscape character of different parts of the country. I have discussed these manifestations in detail on the British fairies blog, but the various fairy forms may be reflections of:

- the unique conditions (and perils) of certain English rivers and ponds, which are personified as lake maidens and river spirits, many of whom are perilous to humans. Examples are Peg Powler on the upper Tees and the widespread Jenny Green Teeth;

- the harsher conditions of the Highlands, the less forgiving nature of the mountains and lochs, might perhaps have been animated through the monstrous water beasts that are such a feature of Scottish folklore. The kelpies, shellycoats and other man-eating beasts of the far north are born of tougher climes.

I always hesitate to be too reductionist and determinist about such matters, but it is undoubtedly the natural tendency of people to imbue the world around them with personality; the tiddy men of the Fens may be another good example, but many of the ‘tribes’ of British fairies (pixies, spriggans, hyter sprites and the like) are quite parochial in their occurrence and might, as such, symbolise or portray particular features or traits of that locality.

Even if we reject such close ties between fairy character and the territories they inhabit, I think we can still see the fays as a response of the British people to the British environment. Even if they are not characterisations of specific landscape features, the still reflect a particular spirit of place. From a common core of elvish traits, over the medieval centuries the British have elaborated their many fairy tribes, each unique to its region.

Another conception of fairy nature is to see them as protectors of the land. This aspect of their nature is particularly emphasised in the modern fairy faith, but it has older roots, at least as far back as the nineteenth century. In the Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The moon of Gomrath, two novels rooted imbued with the spirit of place of Alderley Edge, Alan Garner portrayed how the elves might fall ill as Britain is progressively polluted. From this it is a short step to envisage the fairies of Albion as being dedicated to the preservation of their land- a role I have dramatised myself in The elder queen and in Albion awake!

David Inshaw, Silbury Hill on starry night

The spirits of Albion

The resonance of these ideas derives from a tight bundle of associations. Fairies have very often been connected in folklore with standing stones and megalithic burial chambers. They are thus in some way related to our ancestral dead and, by conceiving of them as spirits of place, we are reaffirming our deep roots in the land, re-establishing connections to racial and national origins and reasserting a sense of belonging to, relating to and respecting the land on which we live and depend.

Fairies and elves may therefore be seen as personifications or embodiments of the spirit of Albion.

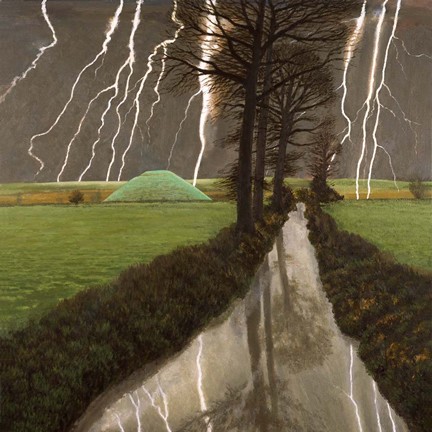

David Inshaw, Storm over Silbury Hill

For more discussion of this general subject, see my 2022 book The Spirits of the Land- Faeries and the Soul of Britain (available on Amazon/KDP as a paperback or e-book).