James Archer, The death of King Arthur

There is no more British myth than that of Arthur and the Round Table, the so-called ‘Matter of Britain.’ Arthur is depicted as hero-saviour. If the original Albion was a mythical giant, the huge personality of Arthur is his present embodiment, a giant figure who overshadows almost all others from both history and fable.

John Garrick, The death of King Arthur

Arthur’s return

“Vain it is, to seek for the grave of Arthur.” (Y beddau/ The graves)

The Matter of Britain is woven into the geography of the British Isles: from Lyonesse (Cornwall), through Glastonbury and Cadbury (Camelot) to Arthur’s Seat near Edinburgh. This is not historical geography, though, but rather living myth and prophecy, because of the promise that King Arthur is not dead and shall return.

As is well known, Arthur was mortally wounded fighting his nephew Mordred, but he did not die on the field of battle at Camlann. Instead, he was carried away to be healed by the fay maidens Morgan and Nimue. From this myth of fairy salvation, a wider supernatural nature developed. Layamon, in his Brut of around 1190, recorded that:

“Bruttes ileveð ɜete þat he beon on live,

And wunnien in Avalun mid fairest alre alfen,

And lokieð evere Bruttes ɜete whan Arður comen liðe”

“The British believe yet that he is alive,

And dwells in Avalon with the fairest of all the elves

And the British ever yet expect when he shall return.”

As we have seen from the old Welsh verse, Arthur lacked any known grave, so that the story of his survival was fostered (William of Malmesbury, The deeds of the kings of England, 1125). This idea became firmly established amongst the Welsh, Cornish and Bretons, and then spread to the English:

“He is yet in Avalon, awaited of the Britons; for they say and deem he will return from whence he went and live again.” (Wace, Roman de Brut, 1155)

“Yet your relations the Britons deny his death and regularly expect his coming.” (Henry of Huntingdon, History of England, 1154)

Monastic writer Gerald of Wales was particularly outspoken on the subject. In De principis instructione (of about 1195) he mentioned the discovery of Arthur’s tomb at Glastonbury, adding:

“… the legends had always encouraged us to believe that there was something otherworldy about his ending, that he had resisted death and had been spirited away to some far-distant spot.” (I, 20)

Gerald returned to the subject in his Speculum ecclesiae of about 1216, in which his views on his fellow Welshmen’s beliefs about Arthur are made rather more forcefully:

“Many tales are told and many legends have been invented about King Arthur and his mysterious ending. In their stupidity the British people maintain that he is still alive…. [and that] the King will return in strength and power, to rule over the Britons, as they think… wherefore they await his coming, as the Jews their Messiah…” (II, 8-10)

Gerald then repeated, in greater detail, his account of the discovery of the king’s tomb at Glastonbury Abbey. His reason for writing was to support the English Plantagenet claims to dominion over Wales, whilst the Abbey needed the money from visitors to pay for repairs. The tomb was fairly evidently a fake- not least the lead cross marking it, which announced that Arthur lay buried there “in the Isle of Avalon.” There seems little reason to record on a tomb where it is, as anyone reading the inscription can probably be assumed to know where they are already… Arthur’s remains had not been unearthed and the legend (like the king) lived on.

Holinshed, several centuries later in 1578, told much the same story as the earlier writers. People believed that “King Arthur was not dead, but carried away by the fairies into some pleasant place, where he should remain for a time and then return and reign again in as great authority as ever.” (Chronicles, Book V, c.14) In The fall of princes (Book VIII, c.24), Lydgate had developed the story further:

“He is a king y-crowned in Faërie,

With his sceptre and pall, and with his regalty,

Shalle resort, as lord and sovereigne,

Out of Faërie and reign in Bretaine,

And repair again the oulde Rounde table.”

In the Morte d’Arthur Malory was more circumspect on the subject “I find no more written in my copy of the certainty of his death” (c.167). Later, he expanded: “Some men say in many parts of England that King Arthur is not dead, but had by the will of our lord Jesus Christ into another place and men say that he will come again and he shall win the holy cross. But many say that there is, written upon his tomb, this verse: ‘Hic jacet Arthurus, rex quondam, rexque futuris.“” (c.168) (Here lies Arthur, the once and future king.) Rather as with the Glastonbury inscription, we may note that curious declaration on the monument- that this is the grave of a king who is, in fact, not actually dead at all…

Malory’s vagueness was inherited by Tennyson in the Idylls of the King, in which Arthur- just before his departure for Avilion- merely observes that “Merlin sware that I should come again/ To rule once more; but let what will be, be.” (The passing of Arthur, lines 192-3). The Reverend Robert Hawker was rather more assertive in a verse he addressed to Tennyson:

“They told me in their shadowy phrase,

Caught from a tale gone by,

That Arthur, King of Cornish praise,

Died not, and would not die.

Dreams they had, that in fairy bowers

Their living warrior lies,

Or wears a garland of the flowers

That grow in Paradise.” (To Alfred Tennyson)

In any case, though, by the mid-nineteenth century the belief in the King’s survival and centuries’ long slumber was very well established in popular belief and needed little bolstering from literature.

So it is that Arthur sleeps with the fairies in many caves and hills across the land of Britain. He is to be found in Scotland under Arthur’s Seat, Edinburgh, and beneath the Eildon Hills; in Wales he slumbers at Caerleon, Craig-y-Ddinas, Llandegai, Ogo’r Dinas, on Anglesey, in a cave beneath Snowdon and at Pumsaint near Lampeter. In England there are tales of the waiting king in numerous locations: at Sewingshields, Ravenglass, Blencathra, Dunstanburgh, Freeburgh, Richmond Castle, Alderley Edge and South Cadbury, to name but a few locations.

To each of these sites folk tales of the discovery and waking of the king are attached. These locations are, too, still capable of generating romantic fiction, as in Alan Garner’s Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The moon of Gomrath in which magic, faery lore and myth are all entwined.

The meaning of the myth

The sleeping hero who will return to save his people is not a unique myth. It is also told of Francis Drake in England whilst across Europe Arthur, as well as other more local kings and heroes, are said to be sleeping beneath mountains and hills awaiting their call.

What is the source of these widely spread ideas? The origin for Arthur must have been the defeat of the British by the invading English in the sixth and seventh centuries and a yearning for recovery and restitution, but the story was subsequently adopted enthusiastically by the conquering English too. Why was that? They had no need of its comfort in the face of dispossession and defeat.

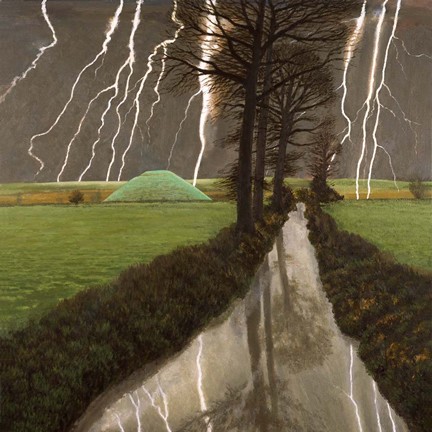

The attraction of the Arthurian legend is that offers hope and reassurance in a nation’s darkest hours, of course, and may confer too some sense of special status. Perhaps, in addition, there is some very much deeper resonance with ancestral dead. Arthur was taken by the fays to fairyland beneath the hills; the fays have long been associated with tumuli and other ancient sites and, very possibly, both strands of popular belief link us to very ancient concepts of ancestors sleeping beneath the barrows and offering us guidance and protection.

At the very least, the thought of a returning hero gives encouragement and support. To quote (completely out of their original context) the lyrics of Asian Dub Foundation in their song Naxalite:

“A prophecy that we will rise again

Again and again until the land is ours

Again and again until we have taken the power.”

What the sleeping hero represents, above all then, is a rallying point. Arthur is a focus for resistance to an unspecified enemy or threat. He belongs to the land, to the people, and we identify with him and derive strength from the knowledge that he is a permanent confirmation of our right to live and belong.

Edward Burne Jones

For more discussion of the Arthurian myth, see my 2022 book The Spirits of the Land- Faeries and the Soul of Britain (available on Amazon/KDP as a paperback or e-book) and my earlier Who’s Who in Faeryland? (Green Magic Publishing).