“Much have I revelled in the realms below/ And many goodly parts of maidens seen…”

with profuse apologies to John Keats

I recently been reading Pierre Louys’ collection of erotic verses, Pybrac. I have mentioned Louys previously, discussing his faux classical Greek paean to lesbian love, Bilitis. That book, and another classical pastiche, Aphrodite, were his main published works during his lifetime. However, when he died in 1925, it was discovered that Louys had written vast quantities of unpublished material, both poetry and prose. The main reason that all of this output was unknown was because of its scurrilous content. Much of this writing has since been published, but it has changed somewhat our view of the author. No longer is Louys so much seen as a promoter of diversity; rather, he must be regarded as a outrageously erotic fantasist.

Pybrac is a series of just over three hundred four line poems, almost all beginning “Je n’aime pas a voir” (I don’t like to see). What Louys didn’t like to see was a vast array of more or less unusual sexual practices, from dykes with dildos to buggery and bestiality. Of course, he’s writing about them precisely because he does want to see them- and to describe them in detail to us. Very little is left to our imaginations at the end of this. If you ever felt any curiosity about what shepherdesses might conceivably get up to with goats, cart drivers with their horses or (comparatively conventionally) brothers with their sisters, this is the book for you.

The copy of Pybrac I read was the edition published by Wakefield Press, with illustrations by the Czech Surrealist Toyen. It’s a gorgeous little volume with decorative endpapers and selling at about £10/ $12. It’s not very long, but you might say it’s good value: so much shock value for so little expense!

I think the most important observation is that we ought not to try to judge late nineteenth or early twentieth century French society on the basis of Louys’ overheated and fantastical obscenities. None of it is meant literally or seriously and it is certainly not (I’m pretty sure) a genuine document reflecting the sexual mores of fin de siecle society. If it is, well, what it tells us is (as a notable example) that sex with girls under sixteen or so was pretty common (about a third of the verses describe it) and that, of these cases, about a quarter were incestuous, just under a fifth were lesbian (whether with girlfriends, sisters or even mothers) and anal sex was enjoyed in about a third of the cases. In Louys’ parody of manuals instructing young women in etiquette , The Young Girl’s Handbook of Good Manners, the content is entirely sexual: about half is heterosexual, but about a quarter deals with masturbation and another quarter with lesbian relationships. Buggery and masturbation of partners is quite popular, but most of Louys’ advice is on good manners in oral sex with lovers of both genders (including siblings and parents).

The impression, created by Bilitis and Aphrodite, that Louys was pretty fascinated by lesbian relationships is strongly reinforced by his later output. However, whilst Louys’ earlier books were as interested in same gender love, partnerships and marriage as in sex, his unpublished manuscripts are, in the main, obsessed with the carnal affairs alone. A case in point is the novella Trois filles de leur mere (Three daughters of their mother) which was also published after the author’s death. This is a very short story, set over barely a week, and very little happens in it except a great deal of intercourse. The mother, and her three daughters, who are aged from about nine to twenty, work as prostitutes, mainly offering clients their bottoms. When they’re not being paid to have sex, the family are very busy with each other. Then a young student enters their lives and they all to go to bed with him in turn. The story is scandalous, preposterous and (if you’re not in the right mood) highly disgusting and offensive; it’s pure and utter fantasy that can have very little (if any) basis in the reality of young French females at the start of the last century (but then, perhaps, that’s exactly what porn or erotica is meant to be).

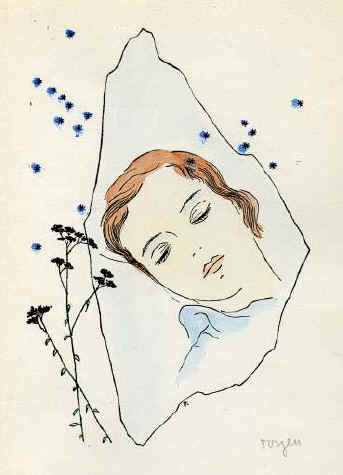

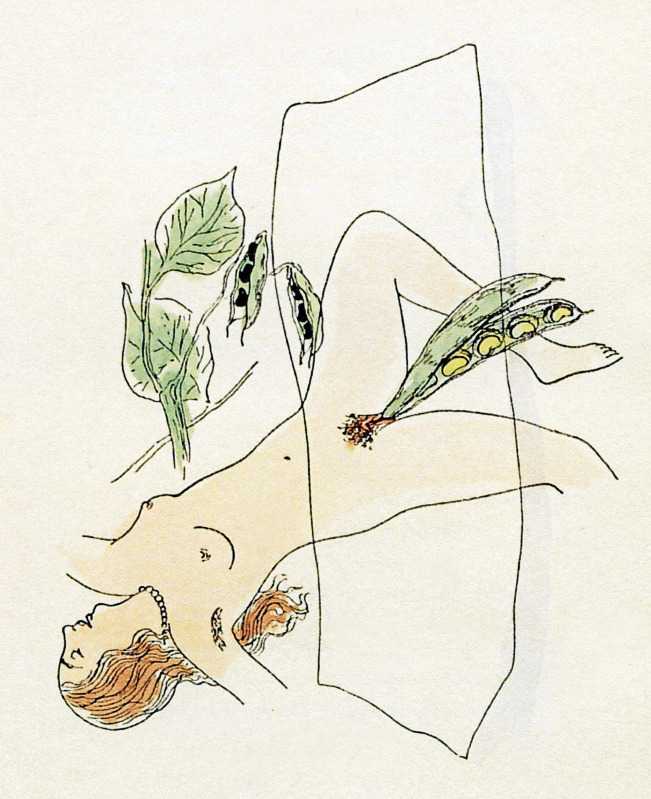

Whatever the literary merits of Louys’ work, and despite his extravagantly kinky content, his works have been through numerous editions and have been illustrated by a range of notable artists. I reproduced some of these pictures in my last posting on Pierre Louys. The images produced to accompany his collections of erotic poems, Pybrac, Cydalise and the Poesies Erotiques, are as every bit as explicit as the text they accompany. Again, I’d advise not searching for these if you feel you might be shocked or offended: most of the illustrators left very little to the imagination. Toyen (Marie Čermínová) was something of an exception in this. Her delicate line drawings are relatively restrained, but the powerful fascination with sex and sexuality is evident nonetheless. This interest was strong amongst the Surrealists anyway, in addition to which her husband, the artist Jindřich Štyrský, issued the journal Erotická Revue between 1930 and 1933 and much of his own work comprised collages made from hardcore pornography (which I too was surprised to discover existed in the 1930s). Toyen illustrated several other books: these included Felix Salten’s Josefine Mutzenbacher, Aubrey Beardsley’s Venus and Tannhauser (both 1930) and de Sade’s Justine (1932), so it’s clear that she had no objection to working with challenging and provocative material.

Rather like Gerda Wegener, whom I discussed a little while ago, Toyen’s gender and sexuality seem to have been quite fluid, so perhaps she found some of Louys’ work appealing for its courageous challenges to contemporary norms. As I suggested in my posting on the work of Jules Pascin, alternative sexualities existed (obviously) but very few writers or painters acknowledged this inevitable fact at the time. For all his smut and provocation, Louys’ attitude was very much that this was part of human nature and, to a considerable extent, unremarkable.

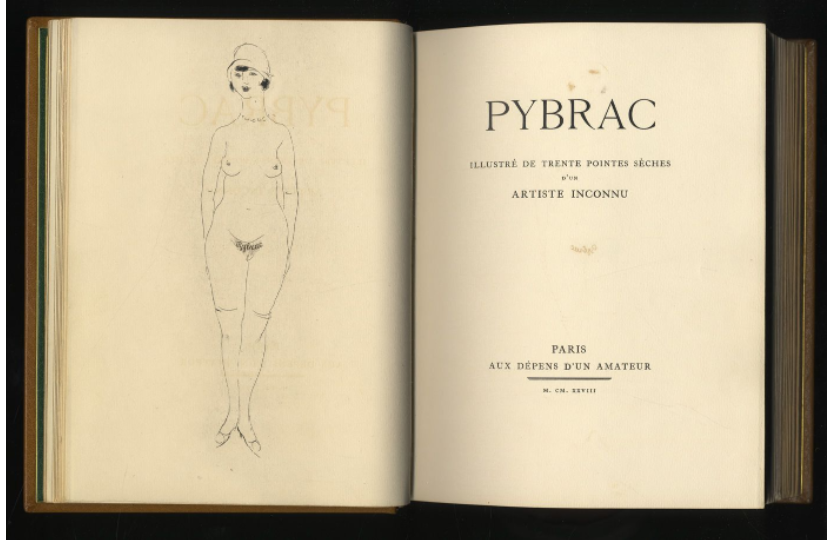

Toyen did not work on the first edition of Pybrac. That appeared in 1927, just two years after the author’s death; it featured a woodcut on the titlepage by Leonard Foujita and internal full page plates by (it seems) Rojan. These were close illustrations of the activities described in the quatrains and not really suitable for posting on WordPress; the same (largely) was the case with the thirty illustrations provided by Marcel Vertes for a further edition in 1928 (reprinted in 1930)- although I include the titles pages here. There was another explicit edition, illustrated by another woman, the little known but prolific German graphic artist Erika Plehn (1904-88), which was published in 1927.

Toyen’s 1932 edition was closely followed in 1933 by a further one (titled this time Pibrac) with head and tail pieces provided by Louis Berthomme Saint-Andre and 32 vignettes by Andre Collot (apparently). In the very same year, the Belgian painter and printmaker Marcel Stobbaerts (1899-1979) was commissioned to work on another edition of Pibrac (which was reissued in 1934, ’35 and ’39). His twenty illustrations are brightly coloured and cartoonish- but still rather explicitly obscene. There was another edition post-war in 1946, the illustrator of which I’ve not so far been able to establish.

I’ve just started to read his collected works, so I expect there’ll be more to say on Pierre Louys… See, for example, my discussion of his first novel, Aphrodite, and also about the central role it plays in my book on the cult of Aphrodite, Goddess of Modern Love. See too my consideration of the artwork created to illustrate Louys’ novel, Les Aventures du Roi Pausole.

For more detail of the writing of Pierre Louys, see my Bibliography for him. A longer, fully annotated essay on Pybrac and its sources can be downloaded from my Academia page. For more discussion of the illustrated editions of the works of Pierre Louys in their wider artistic context, see my book In the Garden of Eros, available as a paperback and Kindle e-book from Amazon.