During the later decades of the Victorian era, paintings that recreated the Greek and Roman past were hugely popular. Perhaps, in the minds of the British public, there was some sense of association between the Roman Empire and the British; perhaps it was just a celebration of what was regarded as the epitome of fine artistic taste. Numerous artists adopted the style of the genre and many of them have sunk into obscurity since. Three here are revived.

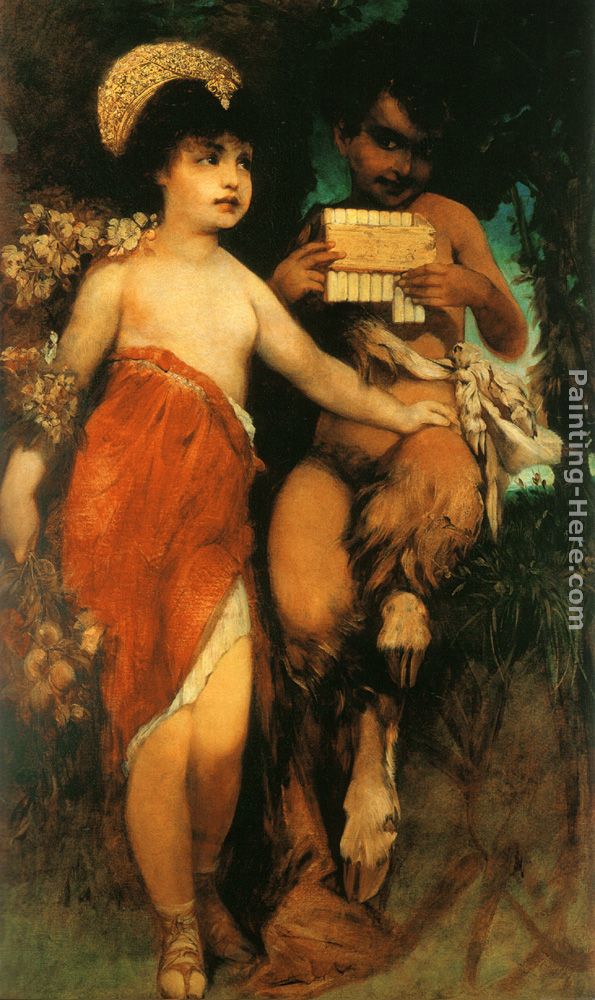

The painter Herbert Gustave Schmalz (1856-1935) was, despite his name, a native British painter who was born in Newcastle and who trained at the South Kensington Art School and then the Royal Academy of Arts, where fellow students included Frank Dicksee and Stanhope Forbes (famed now for his paintings of Cornwall as part of the ‘Newlyn School’). In his painting, Schmalz often managed to live up to the meaning his name has acquired in English in recent decades; he favoured inspiringly lofty and noble heroes and heroines and sickly religious scenes, almost all burdened with improving messages. His Temple of Eros, painted in 1883 (above), imagines some ceremony in which the young erote is worshipped and invoked by a fervent crowd. I assume, judging by the sombre expressions of the celebrants, that loves lost and unrequited are the subject of their appeals to the divinity.

In his 1888 picture, Faithful unto Death, Schmalz confounded the doubters and managed to achieve what might- to many- have appeared impossible: he combined a tribute to early Christian martyrs with a depiction of a bevy of naked young women, all of them bound to posts in a sort of holy fetish fantasy. It’s simultaneously high-minded and tacky.

Born in Bristol, Arthur Drummond (1871-1951) was the son of the marine painter John Drummond. He received his formal artistic training from Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema at the Royal Academy and later studied under Benjamin Constant and J.P. Laurens in Paris. He exhibited his first work at the RA in 1890 and continued to show there until 1901; he also exhibited works at the Royal Society of Artists in Birmingham and the Royal institute of Oil Painters.

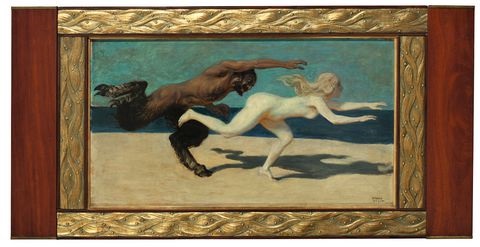

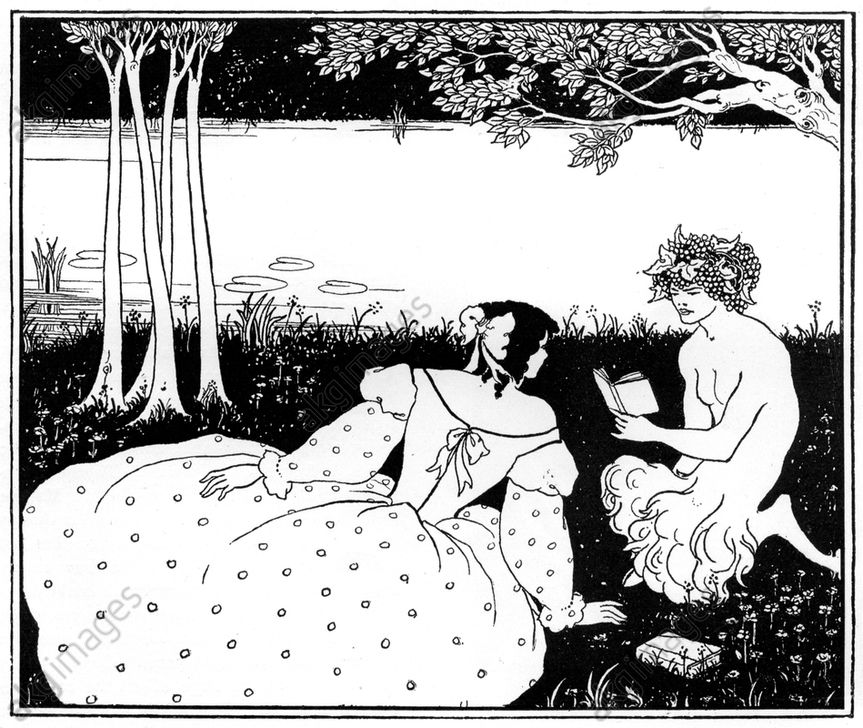

Drummond specialized in history, like his teacher Alma-Tadema, setting many of his works in ancient Greece, Egypt and Rome. He also painted numerous genre scenes showing everyday English life in town and country. These often feature happy families and children looking beguiling. His neo-classicist work can be more intriguing, with the meaning of scenes not so explicit- albeit, still lacking in any real drama or peril. As much as anything, Drummond was interested in painting pretty girls exposing bare flesh and the setting for that was a pretext rather than the primary subject. In this, he is definitely comparable to William Stephen Coleman.

Like very many artists of the time (for instance, Waterhouse, Draper and Coleman), Drummond seems to have used a few models on a repeated basis, as may be seen by comparing The Garland (above) with 1903’s When The World Was Young or the Battle of Flowers (below). Similar clothes are also worn in different scenes, a point which also allows us to note Drummond’s affection for highly transparent fabrics- and slipped garments- that make his art comparable to that of John Godward or William Stephen Coleman.

As well (and combined with) his recreations of classical and Egyptian life, and his streak of orientalism, there is a pleasing whimsy to Drummond’s art that lifts it above some of the art of the neo-classical genre that was so common in late Victorian and early Edwardian Britain. There were numerous painters, such as George Bulleid, Thomas Ralph Spence, Oliver Rhys, Wright Barker and William Reynolds Stephens who churned out portraits of pretty girls on marble terraces- sometimes alone, sometimes lounging with friends in their togas; Drummond added details which make his pictures just that little more individual and memorable. His Girl with Bubble (below), in its attempt to capture motion, even looks forward to such a radical Modernist picture as Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase of 1912.

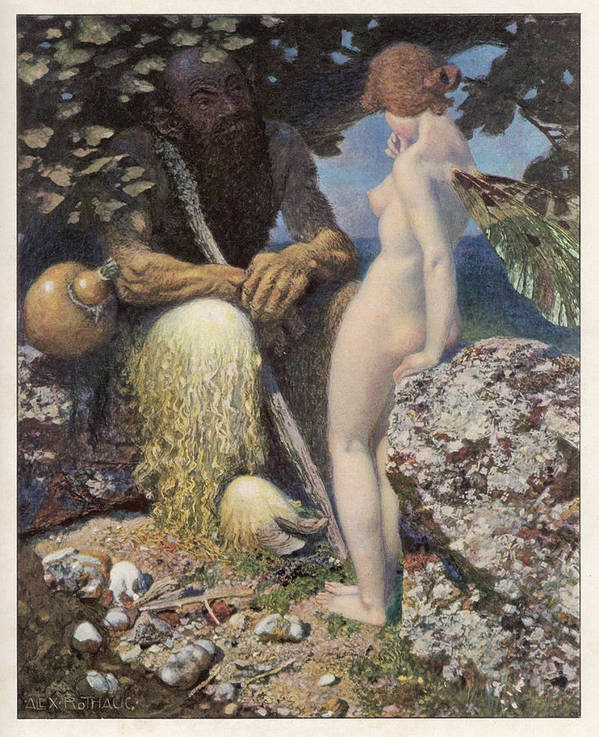

Arthur Hacker (1858–1919) was another British painter in the neo-classical tradition. He was born in Camden, London, the son of an engraver, and studied at the Royal Academy Schools and then with Léon Bonnat in Paris. Hacker began to exhibit at the Royal Academy at the age of twenty and soon attracted public notice. During the early 1880s he travelled in France, Spain, and North Africa, which provided considerable inspiration, and he was soon established as a serious painter in the French academic manner, though he also had strong symbolist influences, evoking comparisons with some of the more dramatic productions of Schwabe, Bocklin, Delville and Hodler. However, whilst female nudes and intense biblical scenes were popular in France, in Britain these themes made him seem distinctly un-English.

Hacker’s sensuous nudes were made palatable to the critics by being couched in tasteful, often classical, allegory: for instance Daphne (1895), The Cloud (1901), and Leaf Drift (1903), which shows three naked women inexplicably lying on an autumn forest floor amidst the accumulating leaf litter. To many today, much of Hacker’s work can seem overblown: his Temptation of Sir Percival (1894, in Leeds City Art Galleries) “borders almost on the ridiculous” according to the Dictionary of National Biography. The same might be said of his melodramatic Vae Victis, an example of several orientalist pictures he painted, themes which also offered plentiful chances for exotic nudes (as with his Death of Cleopatra for example). Vae Victis is highly overwrought, with the wailing women and the captive being carried bodily by the soldier; what’s far worse, of course, is the fact that it plays so unashamedly on the worst Orientalist tastes for images of white women being enslaved by African and Arab males, adding chauvinist to racist insult by adding the women to the piled up spoils of war- jewellery and gold.

Like many other painters I have reviewed on this blog, Hacker’s career was overtaken by the waning taste of the British public for Olympian fine art and, like many of his contemporaries, he took up society portraiture to make a living. He also changed his style to be more post-impressionist manner. Hacker’s art is symptomatic of the attitudes of its time, and it can verge on the risible in some respects, but this shouldn’t wholly efface his great skill as a painter and colourist.

Further Reading

For more information on this genre, see:

- C. Wood, Olympian Dreamers, 1983;

- William Gaunt, Victorian Olympus; and,

- Frances Spalding, Magnificent Dreams- Burne Jones & the Late Victorians, 1978.

For more information on Victorian art, see details of my book Cherry Ripe on my publications page.