As I described in my posting on the statue of the Tinted Venus, the art establishment of Victorian Britain had very fixed and (arguably) hypocritical views on the nature of statuary. Misled by the weathered whiteness of Greek classical sculpture, critics and teachers believed that Greek statues had always been plain unadorned marble- and from this fundamental misconception they elaborated a theory that Greek statuary represented ideal figures that displayed the perfection of human anatomy and which thereby rose above individuality and personal defects.

From this followed an aversion- whether in sculpture or in painting- to any images that seemed too specific, too identifiably individual. As I remarked before, a figure that looked too much like a real woman, involved in real life incidents (and with a real life body- i.e. bodily hair and physical, sexual appetites) was greeted with horror and rejection by the art cognoscenti. This was felt to be a lapse from the lofty ideals of Greek art and it brought art too close to the streets- literally, as I’ve explained, through a chauvinist assumption that the women who worked as models for artists tended also to make money through prostitution- i.e: if a woman found an income through selling her naked body to a painter (however distinguished he might be) there was very little to separate this from any other commercial transaction with her flesh. Even more ridiculous, it was feared that respectable young men would be corrupted by seeing such pictures in art galleries…

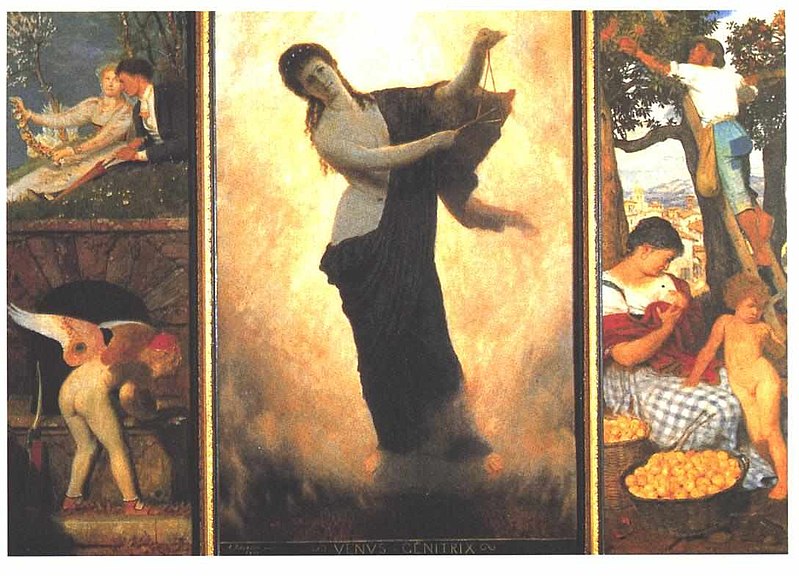

This was plainly appalling nonsense, but it was the prevailing opinion for many years. Artists had to comply with the majority prudery, often turning their nudes into lifeless and marble-like figures. The Victorian tastes for pseudo-classical scenes and for faeries provided acceptable excuses for nudes to be painted, because fantasy and ‘otherness’ helped to distance the bodies from real women in real drawing rooms, but the heavy morality still kept matters within strict limits. Thus, The Times in 1869 declared that French painter Alexandre Cabanel’s Birth of Venus (1863) had overstepped “the fine line which separates the sensuous from the sensual.” Perhaps we can see what they meant: Cabanel’s goddess certainly looks pretty languid and lascivious.

William Etty’s drawing of a Female Nude with a Cast of the Venus de Milo (1833-37) illustrated the model to which young artists training at the Royal Academy and elsewhere aspired; by setting the nude beside the original, he was able to get away with the naked woman. Lord Leighton’s Venus Disrobing of 1867 was praised because it rejected “corrupting Roman notions respecting Venus,” instead of which, the artist had “wisely reverted to the Greek idea of Aphrodite, a goddess worshipped, and by artists painted, as the perfection of female grace and beauty.” She showed very little sign of the “languid, feverous and luxurious dame of love.”As previous posts have highlighted, the Greek Aphrodite was as lascivious and ‘corrupting’ as the Roman Venus, but Victorians pretended not to know this. Likewise Albert Moore’s A Venus of 1869 was praised for being “pure art and not historic or dramatic interest.” It is, in essence, a Greek statue done in oils- and is just as stiff and cold looking as marble can be.

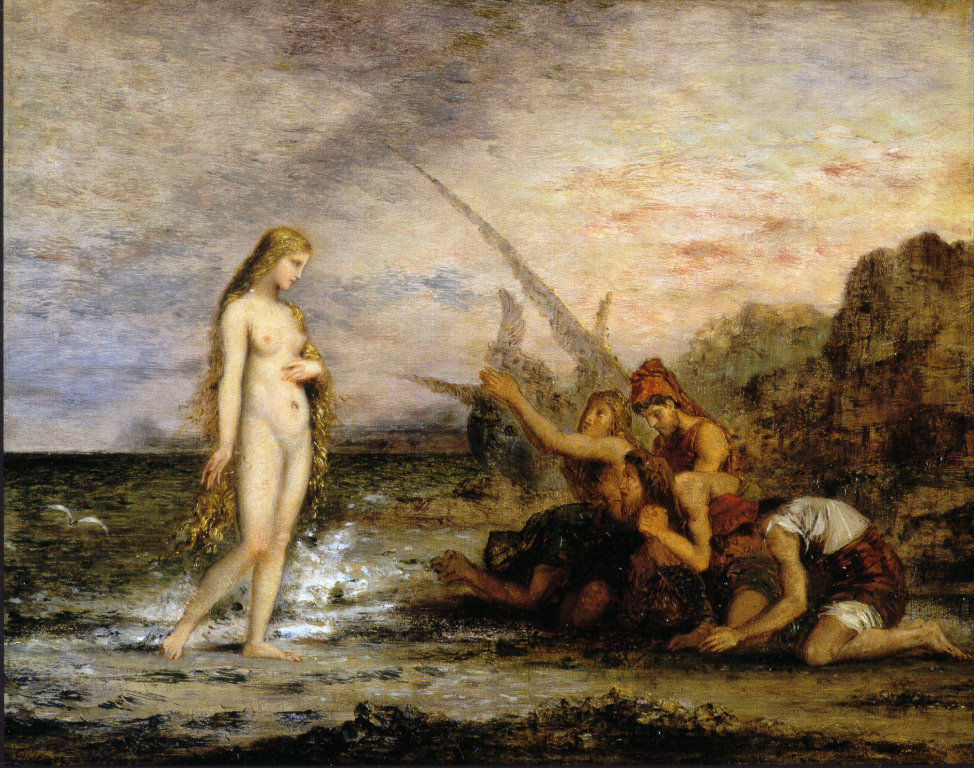

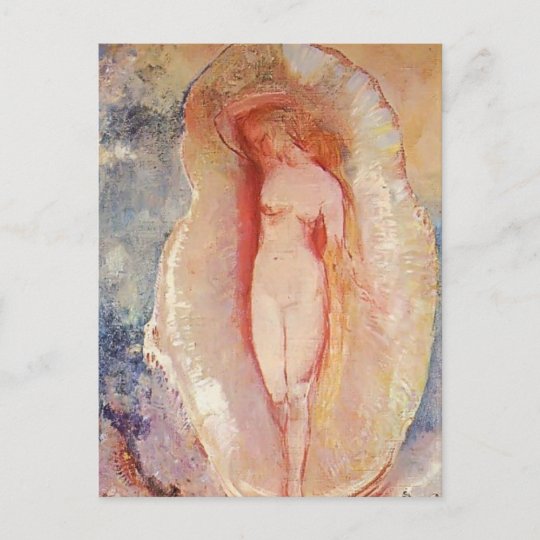

Some artists misjudged this fine balancing act. When Matthew Hale exhibited Psyche at the Throne of Venus in 1879, the Magazine of Art condemned his “belle of the London streets with canary-coloured hair and blackened eyelashes.” William Stott’s Birth of Venus, exhibited in 1887, was condemned by the Manchester Guardian because, “instead of a goddess, [he] has given us a red-haired topsy.” I’d have been rather more concerned by the awkward, doll like pose of this painting than her red hair… Both ‘topsy’ and ‘belle of the streets’ implied that the female was common or ‘low’ and, by implication, of loose morals.

Stott, it must be admitted, was a patchy painter. Another classical scene of his, Diana, Twilight and Dawn, which was painted in 1889 has the same strange stiffness and unlifelike poses that his Venus displayed; plus some faulty perspective too. A similar stiff and slightly unnatural pose can be seen in his Nymph of 1886. His Wild Flower of 1881, displayed in his home town of Oldham, by contrast proves he could just about manage a decent nude when he was in the right mood.

The oddest victim of these attitudes was the Royal Academician Sir Edward Poynter. He painted a Venus Diadumene in 1885. It showed a completely naked woman about to enter the pool of a Roman bath and attracted considerable adverse commentary. So controversial did the picture prove, in fact, that he was unable to sell it and had to add a robe, covering her legs and lower body, in 1893- after which it was soon sold to a collector in the USA.

Double standards were at work here. Bared breasts were acceptable apparently- as, oddly, was the adolescent nude. In 1894 Poynter painted Idle Fears, a picture closely resembling Diadumene, except for the fact that it shows a naked girl of twelve or thirteen huddling against her mother rather than stepping into the water. Admittedly, we see her from behind, although the same artist’s Outward Bound of 1886 is a more revealing image of a young adolescent, another scene which- for no clear reason- was also deemed entirely acceptable to the public. Probably, as Poynter’s girls are Greeks or Romans, they are therefore far away enough in the past for us to be able to distance ourselves emotionally and morally from them.The same could not be said so readily of Stott’s Wild Flower, although his other young female nudes hid behind the defence of classically-inspired high art. Probably, with this latter scene, he was able to evade criticism by the fact that the girl is seated in a white and characterless studio, the only adornment being the white flowers in a white vase. With these hints of marble purity and an austere aestheticism, Stott probably makes the image ‘ideal’ and impersonal enough to have satisfied the critics.

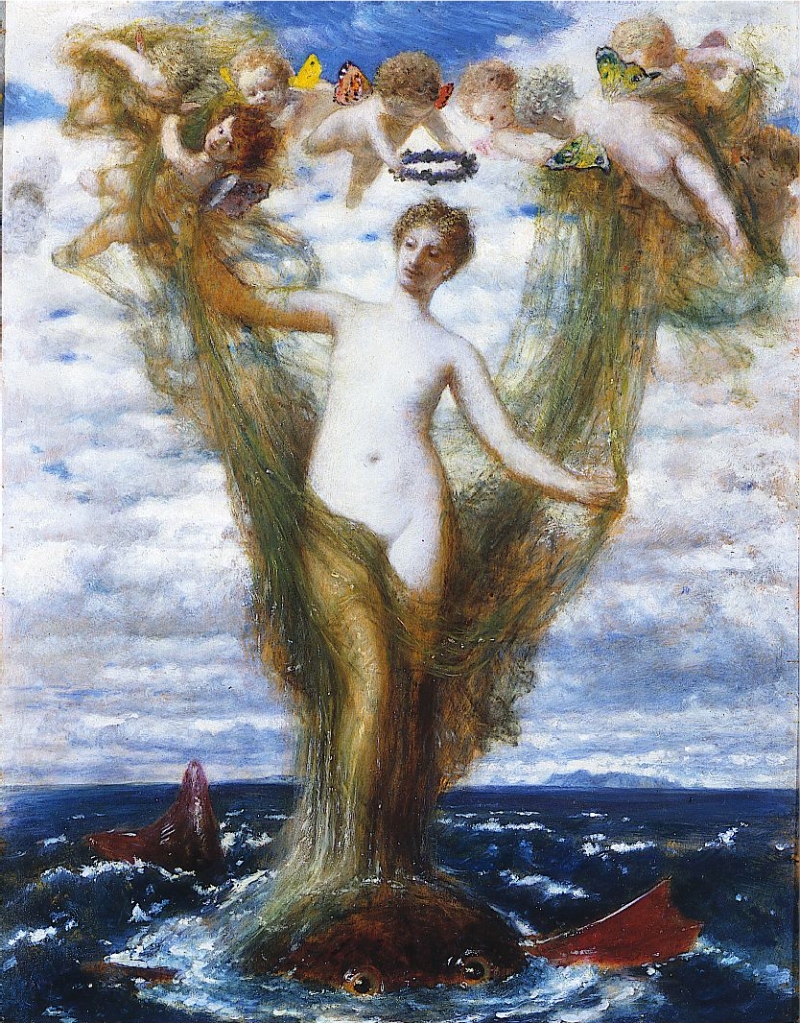

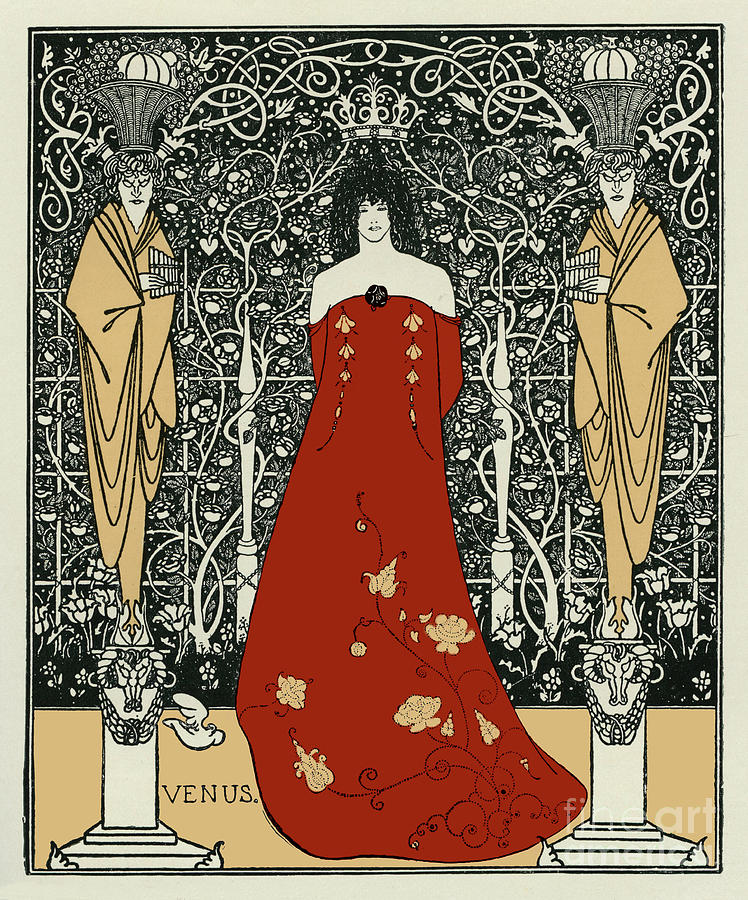

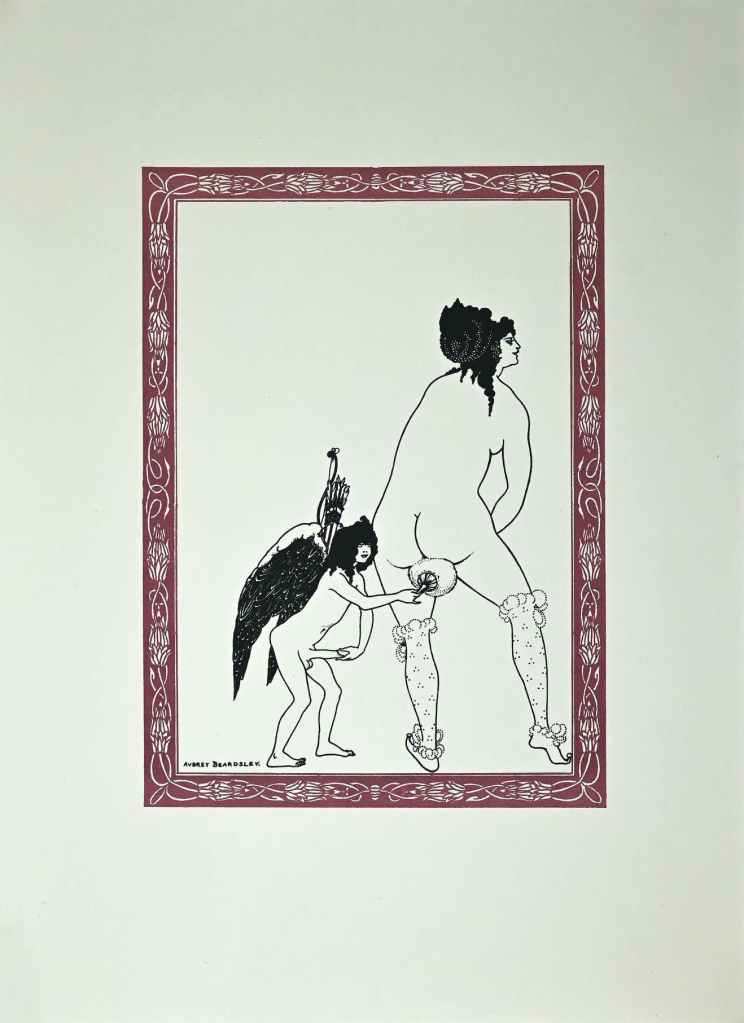

Of course, double standards and hypocrisy were a feature of Victorian society. On the one hand men patronised child brothels, even believing that sex with a virgin could help treat syphilis; on the other hand, an oil painting of an adult woman who looked a little too wanton was an outrage to public morals and presented a danger of giving impressionable young men ideas. These scruples notwithstanding, artists were drawn again and again to Venus/ Aphrodite, because the power of the goddess of love remained irresistible. For more information on late nineteenth and early twentieth century art history, see my books page.