Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959) was an Austrian printmaker, illustrator and occasional writer.

In 1898, after a failed apprenticeship with a photographer, a suicide attempt (on his mother’s grave with a rusty, faulty gun) and a nervous breakdown (for which he was hospitalised for a time), Kubin began training as an artist at a private academy. He didn’t complete this course, seemingly impatient to progress his career, for he enrolled at the Munich Academy the next year.

In Munich, Kubin began to visit art galleries and first encountered the work of Odilon Redon , Edvard Munch, James Ensor, Félicien Rops, Aubrey Beardsley and Max Klinger. The latter’s series of prints, Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove, which I have described before, had a particular impact on the young and impressionable artist. Of this “cascade of visions,” he declared “Here an absolutely new art was thrown open to me, which offered free play for the imaginative expression of every conceivable world of feeling… I swore that I would dedicate my life to the creation of similar works”.

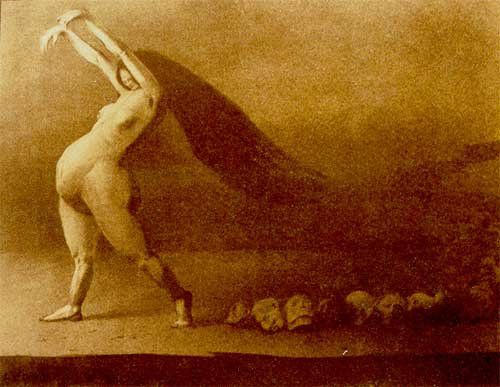

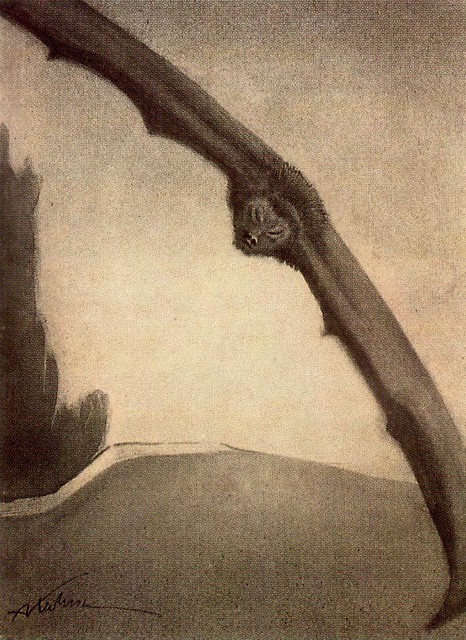

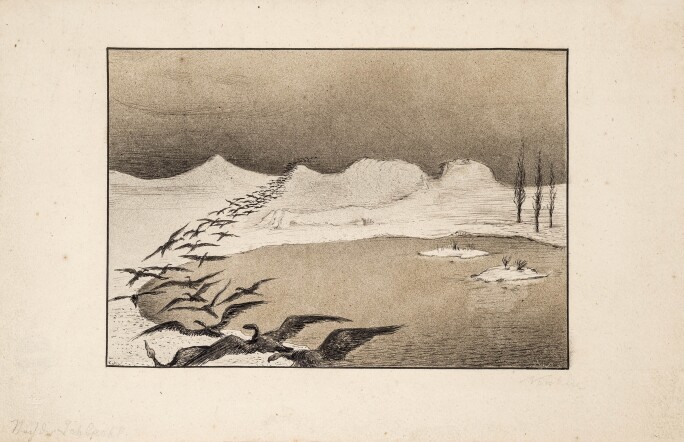

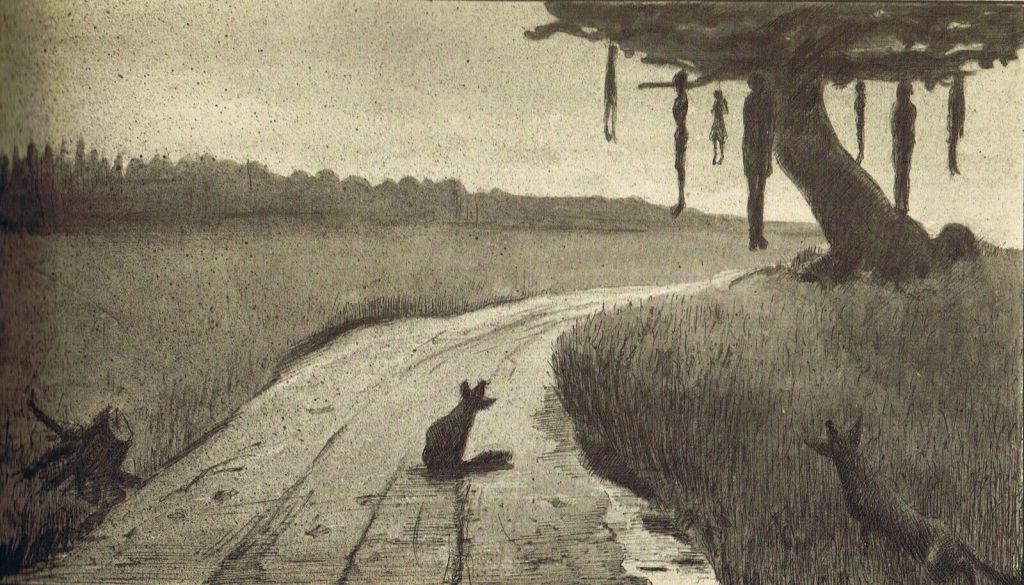

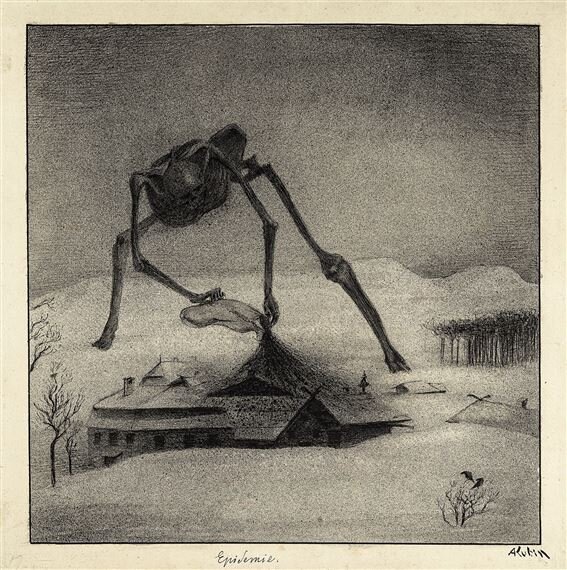

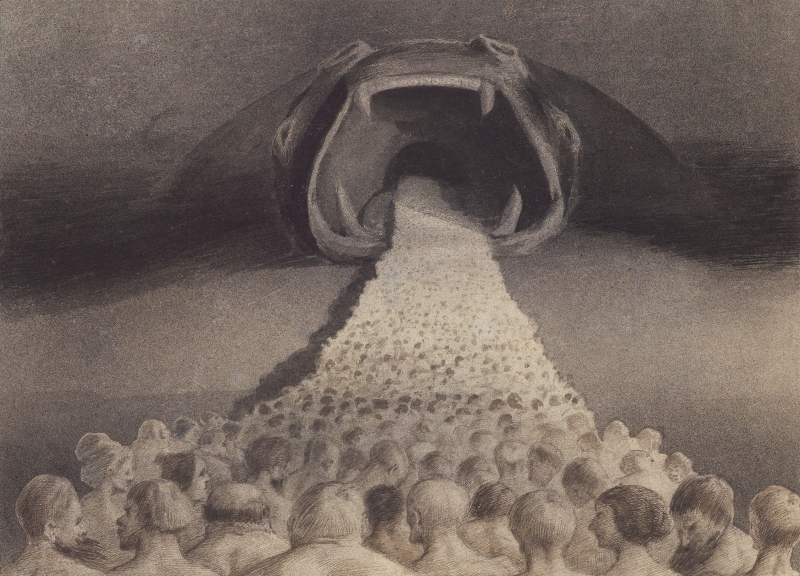

Inspired by Klinger and Goya- and by a visit to Redon in Paris in 1905- Kubin began to produce fantastical, macabre drawings in pen and ink, with some watercolour washes. Although initially associated with the Blaue Reiter group of expressionists, from 1906 he gradually became ever more withdrawn and isolated and lost contact with the artistic avant-garde. Despite (or perhaps because) of his solitary life, Kubin was prodigiously productive and inventive, especially during the first decade of the new century. In total he produced between six and seven thousand drawings- of which just a few are selected here. Kubin’s art, stylistically, looked back to Symbolism with its morbid and supernatural elements. Like Goya, he often created thematic series of drawings, regularly dealing with issues such as sexual violence, human suffering and magical, malevolent female power. After Germany absorbed Austria in 1938, Kubin’s output was condemned as ‘degenerate’- perhaps this isn’t surprising given that he had termed himself “the artistic gravedigger of the Austrian empire.”

Kubin also worked as an illustrator, designing plates for editions of works by Edgar Allan Poe, E. T. A. Hoffmann and Dostoevsky, amongst others. He was also an author in his own right, albeit of just one book, Die andere Seite (‘The Other Side’) in 1908, a fantasy novel set in an imaginary land. In the story’s epilogue, Kubin revealingly declared “I loved Death, loved her ecstatically, as if she were a woman; I was transported with rapture… I surrendered completely to her… I was the lover of that glamorous mistress, that glorious princess of the world who is indescribably beautiful in the eyes of those she touches.”

It seems pretty clear that Kubin’s unhappy youth and his troubled mental state contributed directly to the art he created. He may have officially have been cured of his mental illness, but his work suggests an imagination still disturbed- and it can’t have helped that, from the age of nineteen, he was steeped in the rather pessimistic philosophy of Schopenhauer, who saw “misfortune as the general rule.” Kubin recorded how important dreams were for him as a source of artistic inspiration and that when he sat down to create art he was seized by “unspeakable psychic tremors.” From the artists he admired and closely studied, he seems to have retained only the most morbid elements. In his images, women and sex represent danger and power and death is ever present.