The group of expressionist painters calling itself Die Brücke was formed in 1905 in Dresden by Max Pechstein, Erich Heckel (1883-1970) and Ernst Kirchner (1880-1938). Heckel and Kirchner were the key founding members; they had a very clear idea of the purpose and direction of their art. They issued a manifesto calling for a new, youthful generation of artists and art lovers to come forward and assert themselves; underlying this was a clear credo of shock, provocation and revolt against the bourgeois establishment. To some degree, this radical tone was in tune with the spirit of the times. The contemporaneous Wandervögel and Frei Korper Kultur movements (which I described on my post on Fidus) promoted nature and nudism, although their emphasis was upon health and aestheticism rather than Kirchner’s ideas of a liberated sexuality.

This attitude of the Brücke group manifested itself not just in their output but in their whole philosophy and lifestyle. Kirchner’s studio was, consciously, a forum for bohemian dissipation: he displayed paintings, sculptures, wall-hangings and furniture depicting nudity and sex in his studio, which has been described by one art historian as a ‘Temple of Pleasure.’ He personally practised “casual promiscuity” as well as “free and easy nakedness” at home. The female models the group tended to attract were those who were happy with their unconventional and unconstrained conduct. These models frequently became their girlfriends- and vice versa. All of this symbolised naturalness, liberation and a celebration of life. Die Brücke called for “free drawing of free human beings in free naturalness.” The group tried to live as one big family, sharing “everything: flat and floozy.”

These liberal ideas fed through into Kirchner’s basic thinking about the teaching and content of art. As a result, he argued strongly for the importance of life drawing in an artist’s training. He wrote:

“Art is made by human beings. Their own figure is the centre of all art; therefore, its form and proportions are the basis and point of departure for every sensation… That’s why my foremost demand is that every art school should have life drawing as a basic course.”

Moreover, the nude figure, by the very fact of being unclothed, was connected to a more natural, primitive and uncivilised state, beyond the controls of human society (as Fidus would have agreed). It was especially important to Kirchner that models should pose naturally, avoiding ‘academic’ positions and displaying instead the “unformed natural being.” He concentrated on achieving depictions of the body that were as pure and unaffected as possible; they had to be “immediate and undistorted.”

It was into this milieu that the sisters Franziska and Marzella Fehrman were introduced in early 1910. Fränzi was born in 1900, Marzella in about 1895- “Both of them, half child, half woman, abounded with that charming grace which inspired the Brücke artists.” The sisters came from a poor family comprising fifteen children altogether. Doubtless any money they received for their modelling was extremely welcome in their household- perhaps a consideration that overrode parental concerns about the sort of influence the Bohemian artists might have on the two girls. We shouldn’t forget that, at around this time, Egon Schiele in was sketching naked girls in his flat in Vienna and getting arrested in a rural Austrian village for allowing similar models to pose for him in a studio full of his nude studies of his girlfriend and others.

It was Heckel who discovered the two Fehrman girls and he was instantly taken with them- he called Fränzi “a special event.” In his turn, Kirchner too was “utterly captivated” by the pair and they quickly came to feature in many of his studio paintings, as well as the pictures painted on the group’s summer holidays in the countryside around the Moritzburg lakes. Between 1909 and 1911 the group would escape the summer heat in Dresden and visit rural visit Moritzburg, where they aimed for a natural life of swimming and outdoor modelling. Nude painting was central to the work undertaken at the lakes; in addition, the landscape of woods and bushes offered plenty of secluded spots for naked swimming and sunbathing.

For a year, the pair were fully integrated into the life of the Brücke art group, becoming favourites of the painters because of their carefree charm, the “naturalness of the girls’ movements and the unconscious eroticism they radiated.” So important were the sisters that it’s been proposed that painting the two young females affected the entire approach of Die Brücke to the human figure and their style of painting more generally. There are, in fact, so many Fränzi and Marzella canvases by Kirchner that they might almost be classified as an entirely separate class of works by the artist.

Fränzi and Marzella were painted both clothed and nude by the Brücke artists. They were depicted alone, with other children, and with adults. For example, Heckel’s Children on the Couch (1910) shows Fränzi lying naked beside a clothed boy. Kirchner’s Four Bathers (1910) depicts her swimming naked with three nude women at Moritzburg. In Kirchner’s A Visitor in the Studio with Dodo and Marzella, the artist and the female visitor are clothed and having tea whilst the models are loitering nude in the background- a very odd scenario. Max Pechstein’s Yellow and Black Swimsuit (1910 or 1911) shows Fränzi in the foreground, whilst behind her a mixed group of naked men and women troop across a field heading for a dip in a lake. As in Kirchner’s 1910 sketch of Three Figures Seated by the lakes or Fränzi vor Wandbehang (1911), in which she runs naked into the water, it’s perfectly clear that the girls would have mixed freely with unclothed adults.

The girls will sometimes appear in more typically child-like poses: in one picture, we see Fränzi reclining (naked) on a bed, holding up a doll on one of her thighs; in another, she’s lying naked on the floor playing with a cat. Sometimes, too, we see her and her sister playing together nude in the studio (for example, Zwei Madchen, 1909, Marcella and Fränzi in the Studio, Fränzi in the Studio with a Friend, or, Two Children Playing Naked, from 1910). Kirchner’s images of Fränzi certainly don’t manifest any sense of obligation to protect her modesty- for example Squatting Nude Girl (1910) or Kauerndes Mädchen (Squatting Girl) of the same year). Life with the artists was evidently very relaxed and familiar whilst the girls – perhaps because they came from a large family living in very cramped conditions, and perhaps because of their ages- seem to have been very unselfconscious.

The men of the Brücke group drew and painted the sisters naked again and again, in every conceivable pose (seated, lying, crouching, washing in a bath tub on the floor, doing their hair, drinking tea, playing on a swing, laughing and gossiping together). On the evidence, the artists were apparently obsessed with them. The impression created, in fact, is that they were seldom clothed in the artists’ company, so that the few images of them in dresses are actually quite surprising.

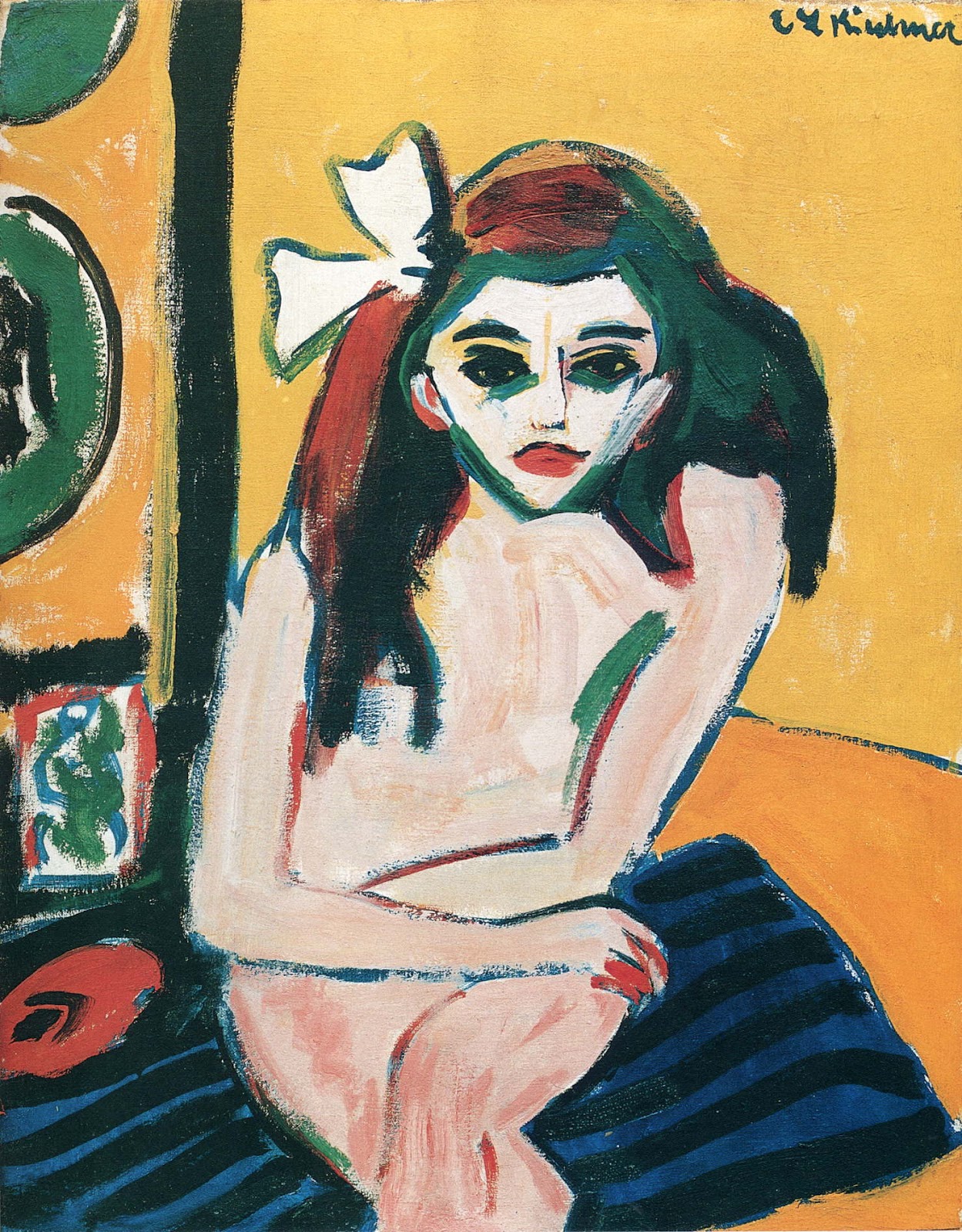

The artists were definitely prepared to paint the girls in a sexualised manner, often having them wear bright red lipstick- see for instance Kirchner’s Marzella of 1909 below. Various art historians have commented upon the “erotic allure” of these pictures, the results being “strangely sick”- in the opinion of one- yet also intense and provocative, showing us a “a girl-woman on the cusp of adolescence, innocent and free yet, at the same time, curious and knowing.” Another writer has described the “physical presence” and “disconcerting character” of these works, which combine their sisters’ childish innocence with a developing self-awareness, thereby depicting the conflict with unresolved yearnings. Pictures of Fränzi in her inexpertly applied make-up highlight the interplay between playfulness and knowing sophistication. The paintings may sometimes have felt problematic for the adults, but there’s little to indicate that they were more than fun, messing around (and probably occasional boredom) for the girls.

Numerous art critics have recognised that the many solo pictures of the girls have a definite erotic charge, and have concluded that Heckel and Kirchner were acutely conscious of the pair’s sexual potential. More notable still are images drawn by Kirchner which show Heckel with Fränzi. The two frequently appear together, one or other (or both) being naked and in close and familiar proximity. They may be playing (as in the picture called Acrobats) or chatting together- in a hammock or on a sofa. Everything indicates that they were happy in each other’s company and content to be unclothed in the other’s presence. The atmosphere may be unembarrassed and familial; it certainly could be described as Bohemian.

So, when Heckel described Fränzi as a “special event,” what did he mean? It seems clear to me that he was responding to her as a whole- both her character and as a physical model. She had an appealing attitude, perhaps playful, derisive, mocking and daring, in addition to which she had no reservations about nude poses. Fränzi wasn’t interested in the fact that they were ‘professional artists,’ or overawed by the implications of that. She probably thought that all the faffing around with easels and paints and brushes was silly- and maybe pretentious- and she humoured them. Sitting around with nothing on was easy and yet it seemed very important to the painters. I suspect that her down to earth attitude was a valuable antidote to the artists being too worried about aesthetics and revolutionary artistic manifestos. The presence of her and her sister would have changed the dynamic of the group and ensured that they stayed light-hearted and playful (as Kirchner’s sketches suggest).

Fränzi would seem to have intrigued Heckel, physically as well as aesthetically, and he recorded his fascination with her in his work. Subsequently, in early 1926, she told Kirchner that her memories of the summers at Moritzburg were “the happiest part” of her life. Whilst our natural response today may be to worry that the girls were at risk of being exploited and abused by the painters, her own attitude to these years appears to have been wholly positive and nostalgic. The group offered her money, holidays away from the city, and fun with grown ups who were lively, liberated and seemed genuinely to like her. It would have been an exciting and different part of her life- an experience that none of her other friends or peers would ever have had- so that we might well understand why it meant such much to her. As for us, we have a charming record of a period full of high hopes and carefree pleasure.

This post is a heavily edited version of my full, annotated discussion of the work of Kirchner, Heckel and Pechstein that’s to be found in my recent book, In the Garden of Eros.