What is it about masks that makes them a symbol of a perverse eroticism? Simply putting on a black mask covering half the face, as is so often seen at masked balls in costume dramas, immediately bespeaks seduction, mystery and illicit love. The mere wearing of the mask, without anything else, signals this to us- along with a range of other subtexts.

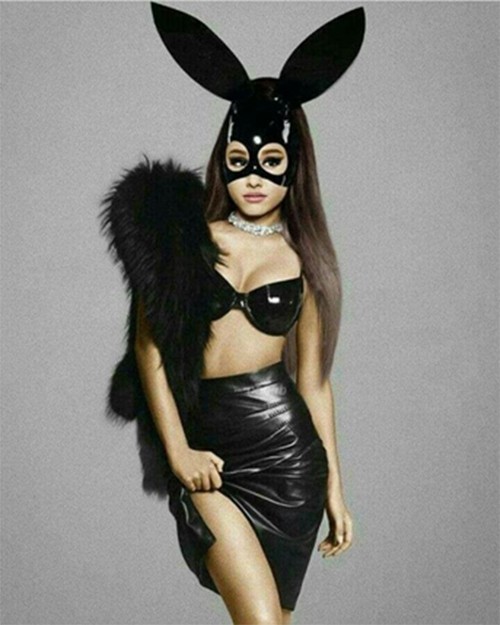

We saw these messages being deployed most recently by Ariana Grande to promote her 2016 album, Dangerous Woman. The implication of the mask is clear: those playful bunny ears belie the fetish, sensual undercurrent. The pvc bra, leather skirt (pulled up to reveal more thigh) and fur stole all suggest sexuality to us, however innocent the expression. There’s a hint of dominatrix, power and control, but somehow, although the outfit is quite revealing, the concealment of the mask preserves the independence of the wearer.

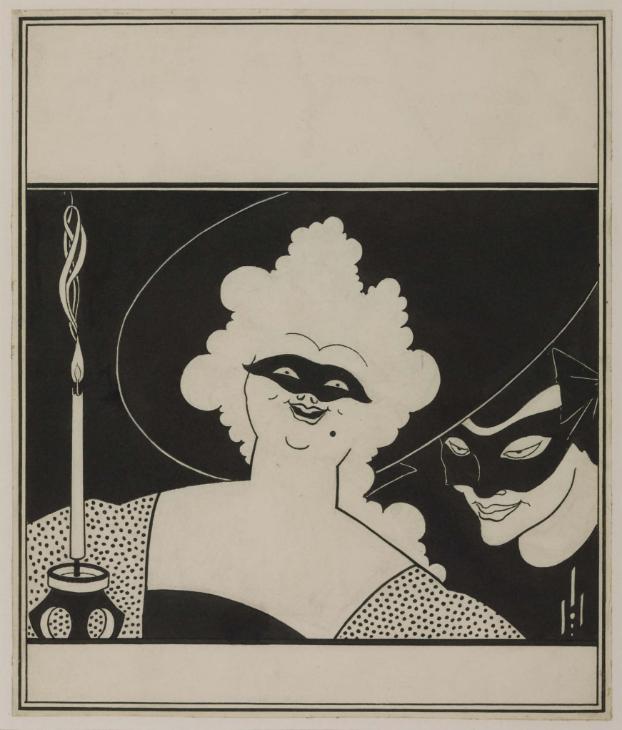

Aubrey Beardsley’s use of masks on the cover of the Yellow Book underlines their connection with a sort of decadent sensuality. For both wearer and observer, the partial anonymity gives a sense of liberation- the individual is free to do what s/he wouldn’t dare to do in normal life. It’s a sanctioned act of losing oneself in the crowd, of abandonment to the erotic impulse, as we see with Pierre-Amedee Marcel-Beronneau’s Masked Woman at the top of the page. The woman caresses her own breast and surrenders herself to pleasure, safe in the feeling that she isn’t constrained by the usual social rules that govern her behaviour; she is released from her known, recognisable social persona.

Given the mask’s rather adult and risque associations, perhaps we are right to detect a certain daring attitude in the expression of the adolescent who’s the subject of Charles-Antoine Coypel’s painting, shown above. She knows she is playing with a slightly illicit aspect of adult life and that she’s sending a bold message, the response to which she might yet not fully be able to handle.

Italian painter Romualdo Locatelli took the erotic suggestiveness of the mask a step further in his 1927 painting La Mascherina. Here, I think, the mask only partly conceals the fact that his model is a rather young woman, meaning that he creates a complex of emotions for viewers. Like Coypel’s, the image is slightly illicit; she is revealing her body, yet she’s disguised; it’s playful yet serious. As she bares her breast, it’s jokey, but provocative- a gesture that’s somehow kept in check by the concealment of the mask.

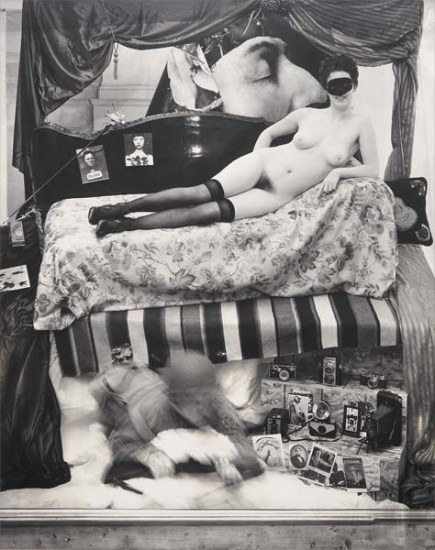

The American photographer Joel-Peter Witkin (born 1939)- whose use of classical imagery, such as centaurs, I’ve described before- has pursued these ideas to even more challenging conclusions. He is known for working with models whom most would hesitate to depict- the obese, the disabled, amputees, and (even) the dead. Witkin very frequently deploys masks, sometimes in more conventional images, such as Fictional Storefront: Camera Store Window, New Mexico, 2004 (below)- a nude adult woman reclined on a bed, but he has also featured them in much more provocative images.

These include Carrot Cake no.1 (1980), a large corpulent woman apparently masturbating with a root vegetable; Portrait of a Vanite, New Mexico, 1994– a one-armed male nude; Melvin Burkhart- Human Oddity, Florida, 1985, an elderly freak show performer who’s hammering a nail into his nostril; Botticelli’s Venus, NYC, 1982 and The Graces- LA, 1988- both featuring naked she-males; The Whine Maker, NM, 1983– a BDSM mistress with gloves, whip and chains (and a baby) and, lastly, Nude with Mask, LA, 1988. This shows a naked girl of perhaps ten or eleven who is reclined languorously across a large armchair, one leg partly raised. Her face and blonde curly hair are half covered by a black mash with pointed cat ears. The disguise the hood provides goes some way to making the child’s nudity less troubling; even so, her lips are slightly parted and the fingers of one hand rest lightly on her upper chest in a vaguely suggestive way. The mask echoes the tone Grande’s playful yet adult headgear but with a far younger wearer, the image, overall, is both striking and disturbing.

Masks are obviously about anonymity, but the purpose of that concealment seems to be to allow things to which we would not consent if our identities, or those of others, were fully revealed. Hiding behind the mask, or permitting others to hide, we can pretend not to know anything about them except what we would both like to imagine. The mystery is as much in the mind as in the garment. Repeatedly, Joel-Peter Witkin has challenged us with just this moral dilemma.